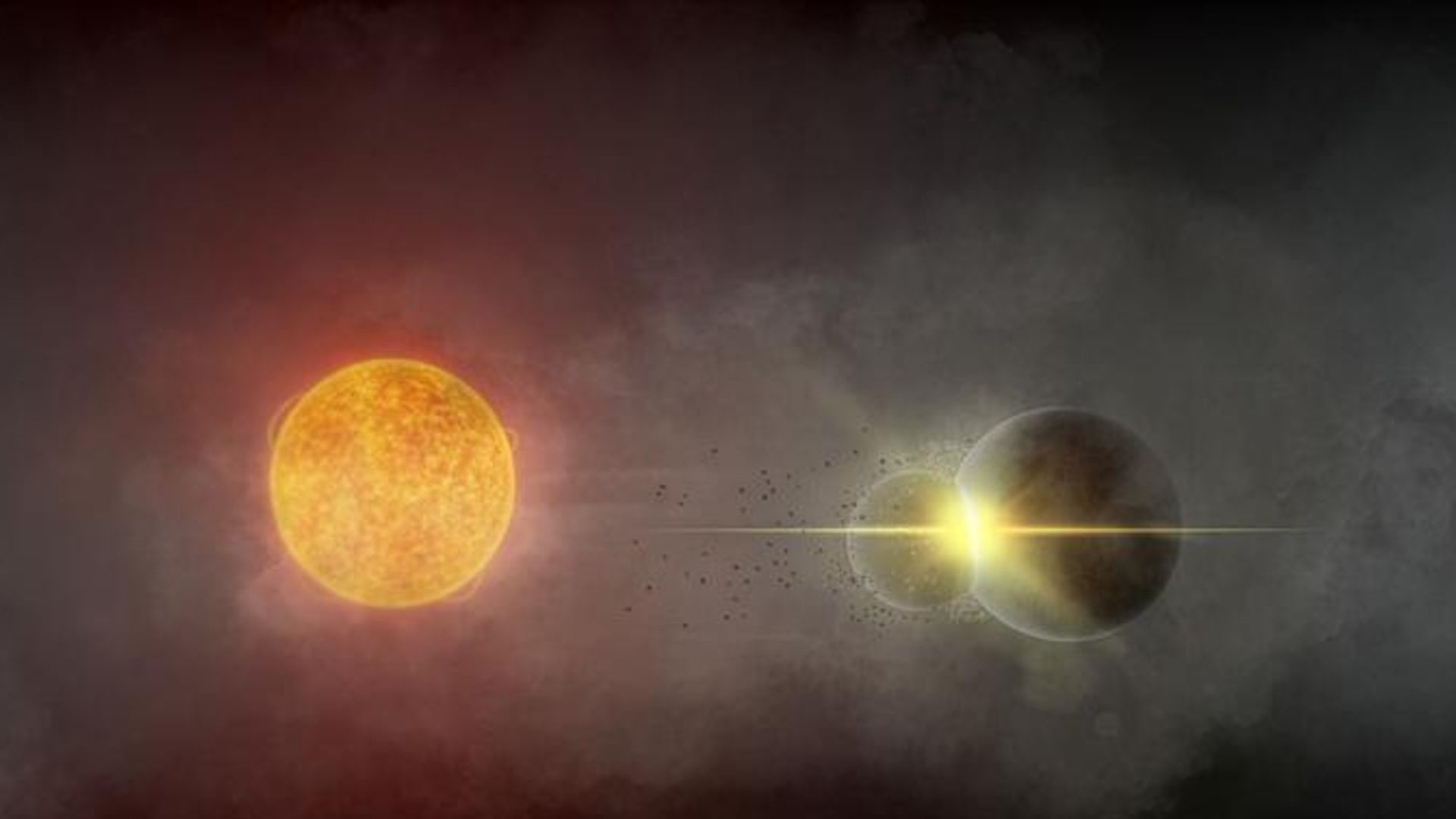

Vanishing lakes in southern Tibet may have triggered earthquakes in the region by “awakening” long-dormant faults in Earth’s crust, researchers say. The finding adds to evidence of an unexpectedly strong link between our planet’s climate and the geological activity deep beneath our feet.

About 115,000 years ago, southern Tibet was home to enormous lakes, some more than 125 miles (200 kilometers) long. Today, those lakes are much smaller. They include Nam Co Lake (also called Namtso Lake or Lake Nam), which is just 45 miles (75 km) long.

A second key point is that southern Tibet is geologically active because of the ongoing collision between India and Eurasia, which began about 50 million years ago. Strain has built up in Earth’s crust beneath southern Tibet, leaving ancient cracks — or faults — in the crust ready to rupture. The geologists reasoned that the slow rise of the crust caused by the shrinking lakes might have triggered such ruptures and generated earthquakes.

The researchers think that this has happened. They analyzed the local geology, mapping the ancient lake shorelines to work out how much water the lakes have lost. They then used computer models to predict how much the crust should have risen in response, revealing that this should have reactivated nearby faults.

The study was published Jan. 17 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Their analysis suggests that water loss from Nam Co Lake between 115,000 and 30,000 years ago led to a total of 50 feet (15 meters) of movement on a nearby fault. The lakes 60 miles (100 km) to the south of Nam Co Lake have lost even more water over the same time period. There, there may have been 230 feet (70 m) of movement on nearby faults.

These calculations suggest that the faults in the region have experienced between 0.008 and 0.06 inches (0.2 and 1.6 millimeters) of movement per year, on average. For comparison, the San Andreas Fault running through California records far more movement: about 0.8 inches (20 mm) each year, on average. But there, the movement is driven largely by processes occurring deep belowground. The new study is evidence that substantial movement on faults can also be affected by processes happening aboveground.

“Surface processes can exert a surprisingly strong influence on the solid Earth,” Matthew Fox, an associate professor of geology at University College London who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. “Geologists are increasingly aware that to fully understand the evolution of a landscape or tectonic region, we need to consider this coupling between surface and deep Earth processes.”

This doesn’t mean earthquakes will occur whenever and wherever lakes are drying up, said Sean Gallen, an associate professor of geology at Colorado State University who was not involved in the research. Such earthquakes will occur only where the lakes sit above crust that has accumulated strain because of tectonic activity. “Tectonics is always the driver,” he told Live Science. “Changes in water load just alter how the built-up tectonic strain is released over time.”

Strain can also be released by other surface processes, Philippe Steer, an assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Rennes in France, told Live Science. Severe storms may trigger sudden and rapid erosion, removing heavy rock from some parts of the crust and allowing it to rise. Quarries where large amounts of rock are removed from the ground have a similar effect, said Steer, who was not involved in the study.

But perhaps the most significant “unloading” events in the recent geological past relate to the last glacial maximum. At that time, about 20,000 years ago, large chunks of North America and Eurasia were weighed down by enormous ice sheets, which were several miles thick in places. Those ice sheets had largely vanished by about 10,000 years ago. But because they were so heavy, the crust beneath where they once lay is still rebounding today.

Some researchers think this may help to explain a long-standing geological mystery. Almost all powerful earthquakes occur along major faults, like the San Andreas, that are found at the boundaries between Earth’s tectonic plates. But occasionally, powerful earthquakes can occur in the middle of a tectonic plate, thousands of miles from one of these boundaries. For instance, in 1811 and 1812, there were three earthquakes of magnitude 7 or 8 along the Mississippi River valley in the central United States.

One idea is that strain slowly accumulated on ancient faults in the Mississippi River valley because of geological activity thousands of miles away, along the edges of the North American tectonic plate. Then, when the ice sheets melted and Earth’s crust began to rise, that strain was released in the form of powerful earthquakes.

“While climate change does not ’cause’ tectonics, it can modulate the stress conditions in the crust,” Fox said. “That’s something we need to factor into future hazard assessments.”

Li, C., Li,H., Chevalier, M.‐L., Pan,J., & Liu, F. (2026). Lake unloading drives fault slip and rift asymmetry in southern Tibet. Geophysical Research Letters, 53, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL120955