The Turkana people, an ethnic group in Kenya, have evolved genetic adaptations to help their bodies conserve water in extreme desert heat, a new study suggests.

Turkana women commonly walk 3 to 6 miles (5 to 10 kilometers) each day while balancing buckets of water on their heads in extreme heat. That means they usually go long periods without drinking water. They also live on a protein-heavy but relatively low-calorie diet of meat, milk and animal blood. Still, their bodies manage to tolerate this intense physical activity in the heat of the desert.

But although this variation may help the Turkana in the desert, Ayroles also believes that, as this community increasingly moves to cities and adapts to modern diets, the variant may come with an increased risk of chronic diseases.

The research team worked with around 5,000 Turkana volunteers. From this group, they first sequenced the full genomes of 367 people, reading their DNA letter by letter. The researchers studied these genomes and found that eight regions had distinct genetic variation, meaning specific genetic variants were more common in the Turkana than in other populations. The strongest signal appeared near the STC1 gene.

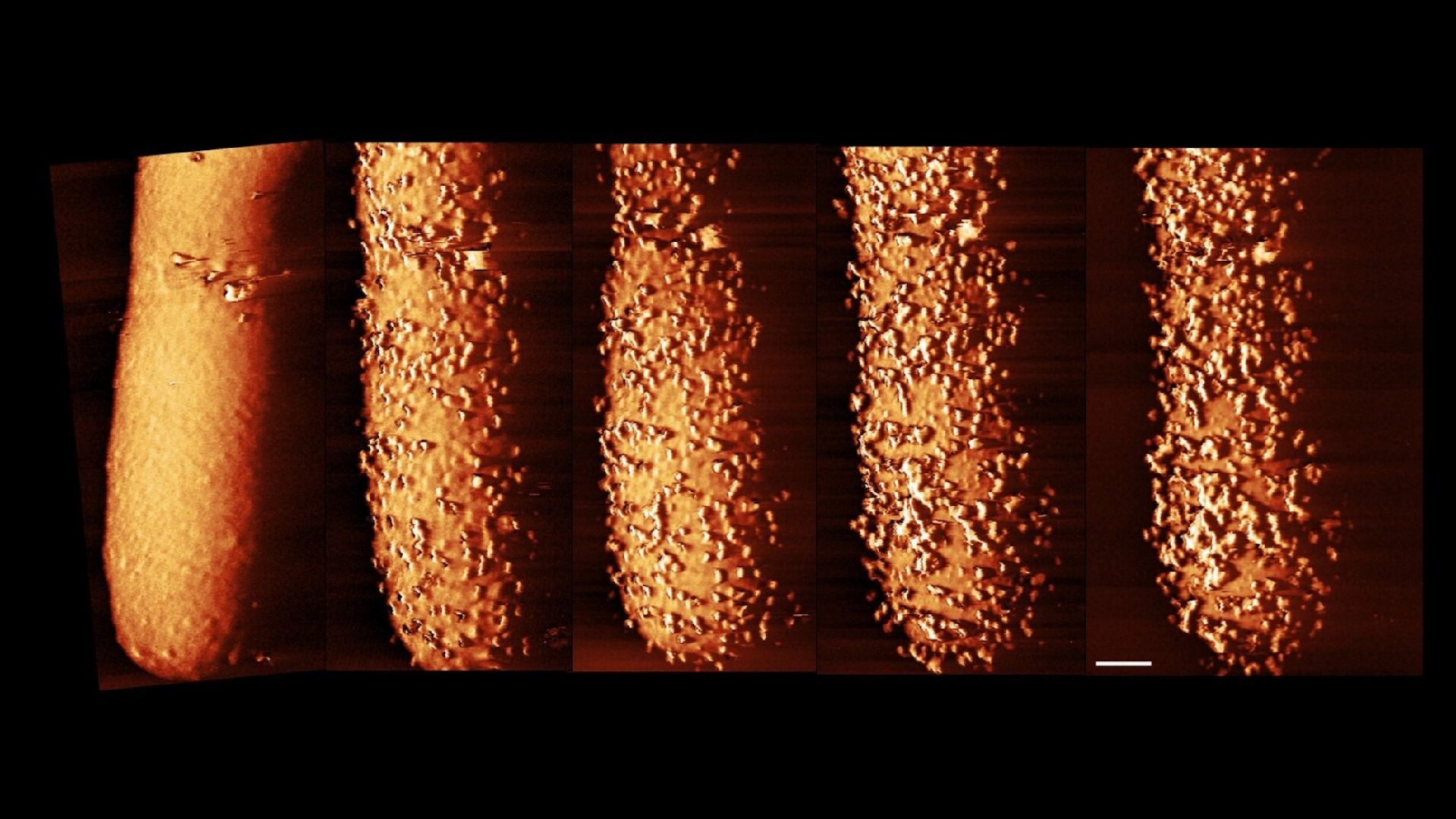

To confirm this proposed function of the STC1 gene, the scientists ran experiments with cells in lab dishes. They took human kidney cells and added antidiuretic hormone (ADH, also called vasopressin), a signal the brain sends to the kidneys when the body is running low on water. The cells responded by switching on the STC1 gene, suggesting that at least one of the gene’s functions is to help conserve water.

Then, Ayroles and his team ran computer simulations to estimate when the observed gene variants may have appeared in the Turkana people. They estimated that natural selection in the STC1 region began roughly 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, around the time pastoralist practices spread through East Africa and the Sahara was drying into a desert.

But nowadays, this genetic adaptation might not be working in the Turkana community’s favor. Beginning in the 1980s, Ayroles said, major droughts and famines forced many Turkana away from nomadic herding and into towns. Their diets shifted from primarily animal products to grain and processed foods, containing flour and sugar.

The team ran additional analyses to better understand the differences between urban and rural Turkana. For example, they tested the kidney function of 447 people using markers like urea and creatinine, and analyzed differences in gene activity among 230 more people.

These results suggested that Turkana people living in urban centers had kidney profiles linked to poorer efficiency, compared with Turkana in rural areas. Their blood also showed higher activity in stress- and inflammation-related genes, which is often associated with a higher risk of chronic conditions, such as heart disease. These findings hint that, in conditions where they are not frequently dehydrated and their diets are more carbohydrate-heavy, the same variant that once helped Turkana people may somehow stress the kidneys and metabolic processes.

“About 80% of the diet of [the Turkana people] is animal byproduct, so meat, milk, and blood; there’s almost no carbs,” Ayroles told Live Science. “And all of the sudden, with food aid or in the cities, carbs are the bulk of the diet. That flip is dramatic, and it’s tied to the same noncommunicable diseases we see in the West.”

“Life there is really rough. These people are heroes,” Ayroles added. “From a biological perspective, though, they’ve done remarkably well.”

Tony Capra, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the work, said the study was “exemplary.”

“I really like this [study]. [It] identifies what I’m sure will become a textbook example of genetic adaptation to an extremely arid environment among the Turkana of northern Kenya,” Capra told Live Science over email. Understanding the genetic basis of human adaptation is challenging. “What makes this study exemplary is its long-term collaboration with Turkana communities and local healthcare workers,” Capra said.

That said, he cautioned that most human adaptations don’t usually come down to a single gene. Instead, they’re more often attributable to variations across many genes, each of which has subtle effects that are harder to detect. So it’s unlikely STC1 is acting alone.

Looking ahead, Ayroles and his team plan to compare the Turkana’s genetic adaptations with those of other desert populations in Africa, India and South America. They also hope to better understand how gene variants that help people thrive in deserts interact with modern, urban life — do they help or hinder the people who carry them? The team thinks understanding these genetic factors could help reveal unsung drivers of chronic diseases.