From Saturday Church.

Photo: Marc J. Franklin

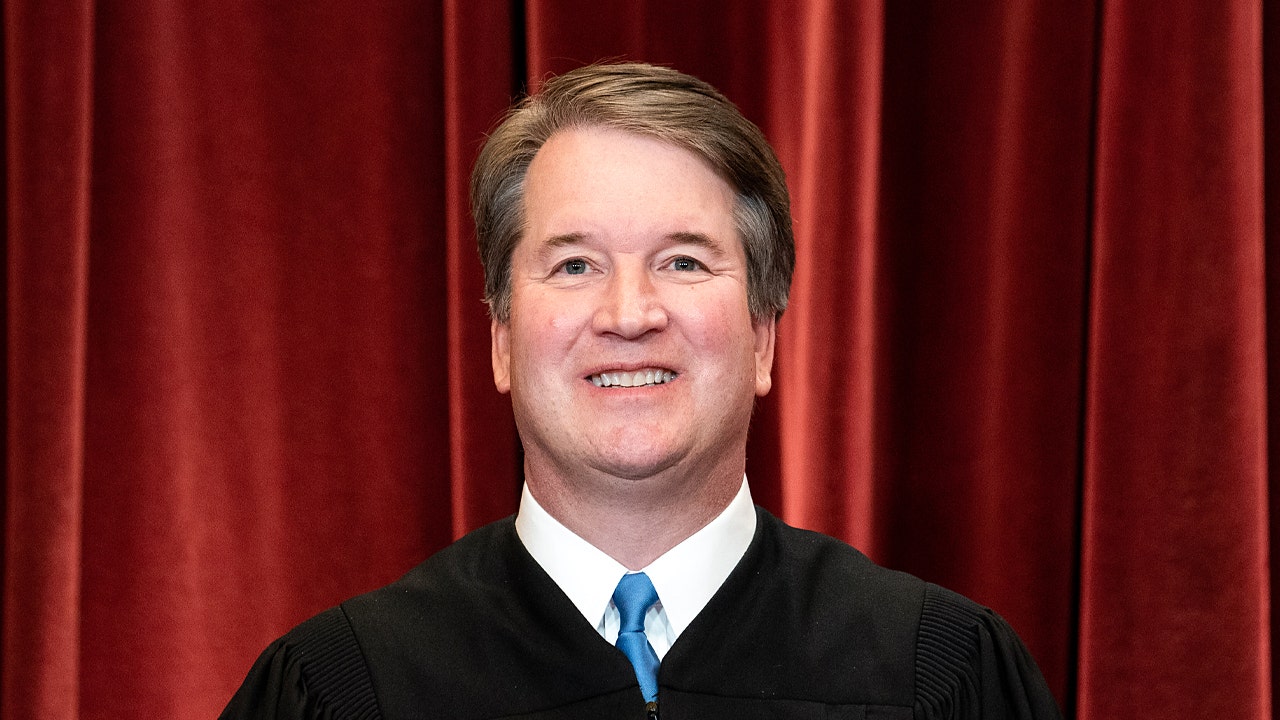

The lyrical register of pop music demands imagery that’s direct and broadly relatable, the kind of message that can be easily understood over a thudding bass line. So too does gospel, where the communion arrives not on Saturday night at the club but at a service the next morning. In either case, the roof might get blown off, and in a moment of mass worship, you’re able to believe for a few minutes at a time in a collective euphoria. The new musical Saturday Church traverses both contexts, following a sensitive Black teenager (played by Bryson Battle) who’s torn between his love of church and his burgeoning understanding of his queerness. The musical has its eye on the ecstatic, and the heavily amplified production directed by Whitney White certainly delivers vocal fireworks. But it’s missing what the genre of musical theater itself ought to provide, which is specificity — a sense of the universal by way of the particular. A song shouldn’t just stay on the register of the broadest possible emotion, and a character shouldn’t just stand in for a type.

Saturday Church, based on the indie film by Damon Cardasis and adapted by Cardasis and James Ijames (of Fat Ham) for the stage, introduces characters so broad it may as well be a parable. When he’s introduced, Ulysses (Battle) is mourning the death of his father alongside his overworked nurse mother, Amara (Kristolyn Lloyd), and his stern churchgoing aunt Rose (Joaquina Kalukango). Rose can’t abide Ulysses’s flamboyance, and she insists that he shouldn’t sing in the church choir even though music is his calling — and Battle really does have a gold-flecked tenor, one that got him plenty of recognition on The Voice. A chance encounter with a doe-eyed boy on the subway named Raymond (Jackson Kanawha Perry) leads Ulysses to a different kind of service: Saturday Church, a support group for young queer and trans youth run by its own imperious matriarch, Ebony (B Noel Thomas). This family is grieving, too, as Ebony has recently lost her partner. She’s trying to pass off her responsibilities to her own found children, played by Caleb Quezon and Anania. The two of them really are hilarious, and they provide Saturday Church with most of its comic relief, bickering like hyenas in a Disney cartoon.

The musical, to its credit, doesn’t lade Ulysses with the self-loathing typical of so many coming-out stories. He knows he’s not straight, he just also knows that his Aunt Rose, especially, would never approve. And Kalukango, who can bring out a fierce intensity in her eyes, finds the fear behind Rose’s stern qualities, the sense that she’s trying not to acknowledge what she also knows about her nephew because she’s scared of the violence that may find him if he lives out and proud. But even as the two worlds pulling at Ulysses establish his conflict, neither place is clearly defined. In Ulysses and Rose’s confrontations, the script gets stuck in loops of the same arguments: Rose soon runs out of coded ways to reiterate how flouncy and flamboyant she finds Ulysses. You cling to the tiny moments of shading — like the way Rose flirts with her pastor, played by J. Harrison Ghee, who also doubles as a vision of Black Jesus who appears before the play’s hero, a bit that starts out delightful and then also wears out its welcome. Ebony, too, is an idea in search of a fuller character. She claims she’s burned out from caring for everyone else at Saturday Church, and yet there’s never much evidence of how it has drained her. We learn very little about her lost partner or of Ulysses’s lost father, other than that both were virtuous. Saturday Church tends to focus on the joy of finding yourself, but that joy would shine more brightly if it allowed its characters to work through more of their entwined grief.

If you’re looking for emotional depths in an otherwise schematic musical, you might hope to find them in the music itself. Saturday Church’s songs, like the rest of the show, keep things on the surface. The show has adopted a bunch of tracks by the pop singer and songwriter Sia, both unreleased music and deep album cuts (including one song used in the Natalie Portman movie Vox Lux), much of it modified by Cardasis and Ijames, who are credited with additional lyrics, and the orchestrator Jason Michael Webb. (There’s also additional music by the DJ Honey Dijon.) Sia’s hits tend to drive emotion like beams of light through neat, often literally prismatic images — “I am titanium,” “we’re beautiful like diamonds in the sky,” “I wanna swing from a chandelier.” The songs at work in Saturday Church occupy a similar grand yet vague aesthetic landscape. Ulysses, in crisis, belts, “Can’t you see I’m wrapped in cellophane?” (from the song “Cellophane”). Were his character more precisely defined, Battle’s wail of feeling might carry you past the awkwardness of the songwriting, the nagging questions about what’s meant to be translucent or not, but here both character and emotion are indistinct. Sia’s work has a tendency toward self-help-style inspiration, a quality Saturday Church does not need more of. Ending the first act, there’s a group performance of a song “Brick by Brick,” which aims toward anthemic and simply lands at generic: Everyone sings, “Can I break these walls down?” Do you normally break down walls one brick at a time?

The treacle, in any case, obscures noble intentions. The Trump administration has, especially in the last week, been motive-hunting for any reason to vilify queer and trans people, and so it’s impressive to see a nonprofit risk whatever paltry amount of federal funding it might still receive. Saturday Church, however, may be so intent on keeping things positive and palatable — to the imagined center-left white cis ticket buyer, one imagines — that it never shifts into other gears. Among their inspiring behaviors, these characters deserve to also express pettiness and selfishness, or, at the very least, more wit. In what’s become its own tedious theatrical cliché, seen in both Fat Ham and Shakespeare in the Park’s Twelfth Night, Saturday Church ends with the characters transformed through drag into more fabulous versions of themselves. They step out to Saturday Church’s title song, which reiterates the phrase, “’cause it’s a queen thing.” The phrase’s partially in reference to clacking a fan, but otherwise, I have no idea how to define what exactly that thing is supposed to be.

_

Anthony Roth Costanzo in Galas.

Photo: Nina Westervelt

Saturday Church leans hard into queer aesthetics, but it never captures the defining quality of camp. For that, head west to Little Island for Galas, where it’s flowing through the Hudson in abundance — overabundance, really, which may be the point. There, Eric Ting directs a revival of Charles Ludlam’s Galas, a tribute to the great operatic soprano Maria Callas, starring the countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo in fiercely wing-tipped eyeliner and a series of showstopping gowns by Jackson Wiederhoeft. Ludlam was a puckish star of the downtown avant-garde before he died, at 44, of AIDS-related complications in 1987. He created Galas with his Ridiculous Theatrical Company in 1983, and the play’s both a dutiful and insane reworking of history, a tribute that could only come from one queen to another. (More than a little of the sensibility of Oh, Mary! originates with Ludlam.) The contours of the story are almost like a biopic: Maria Magdalena Galas — pronounced as if it rhymes with Callas — starts singing for food in Greece during the war, weds an Italian industrialist, loses weight in a mysterious rush, conquers the world with her dramatic and vocal versatility, and then falls for a Greek shipping magnate, here called “Aristotle Plato Socrates Odysseus.” The specifics, like the names, get bonkers. The pope, played by Samora la Perdida, is a mincing oaf who bickers with Galas about the value of translating Wagner. Galas’s maid, played by the essential Mary Testa, is a former opera star herself, one who makes ominous pronouncements of impending doom in between her dusting. The show’s biggest laugh may come when Testa pries open Costanzo’s mouth and pronounces just how many performances of Norma Galas has left. Eighty-six, as it turns out. Fewer, if she insists on playing Isolde too.

Ludlam was clearly as fond of inside opera jokes as he was of broad farce, and it’s a delight to see his work revived. Ting’s production tends toward gilding the lily, even as Galas herself is magisterially going on about how she loves that very phrase. This Galas has the shaggy looseness of a show developed to be staged on the cheap, and it’s easy to imagine the play killing with cardboard set pieces and costumes made of bedsheets. Here, Ting is working with enviable opulence, which can be a double-edged sword in a production at Little Island. (The Threepenny Opera staged there earlier this year faced a similar issue.) The gowns, wigs, sets, setting, and even the cast are all quite luxe: The downtown icon Carmelita Tropicana plays Galas’s Italian industrialist first husband. That plush quality leads you to expect a certain tightness of performance that this Galas hasn’t yet achieved. Tropicana’s casting, for instance, is a great wink in theory, though she’s a less apt choice for a comedic straight man given that she seems more comfortable as a ham than a voice of conscience. Ting and his cast clearly enjoy seeing what it’s possible to get away with in their staging, though sometimes at the expense of the audience’s participation in that fun. An S&M moment between the pope and an attendant goes from funny to tedious. In the extended scenes of the characters cavorting and shouting aboard Aristotle Odysseus’s yacht, you may feel a premature hangover coming on.

Even as the fun wears thin, there’s a reverence to Galas that carries the day, to both Ludlam’s work and Callas herself. Costanzo likes to overachieve in his extracurriculars — last year, he did a near-solo Figaro at Little Island — and to this not-quite Callas, he’s lent both acute comedic timing and his own voice. Ludlam didn’t sing in his staging of the play, but Costanzo does re-create some of Callas’s repertoire. It’s a daring gambit to try to measure up, and also, as it turns out, a touching one. Amid its farce, Ludlam’s play keeps an eye on the weight of a preternatural artistic gift. A great voice transforms a person’s life; it must be properly tended; and it can, as happens to Galas mid-performance, abandon you in an instant. In that context, you watch Costanzo perform those arias, thinking, yes, of the clarity of his tone and expression, but also more pointedly of what a rare gift they are, to perform or receive. Treasure them — because, as performers and audience members, we never know how many we have left.

Saturday Church is at New York Theatre Workshop through October 19.

Galas is at Little Island through September 28.