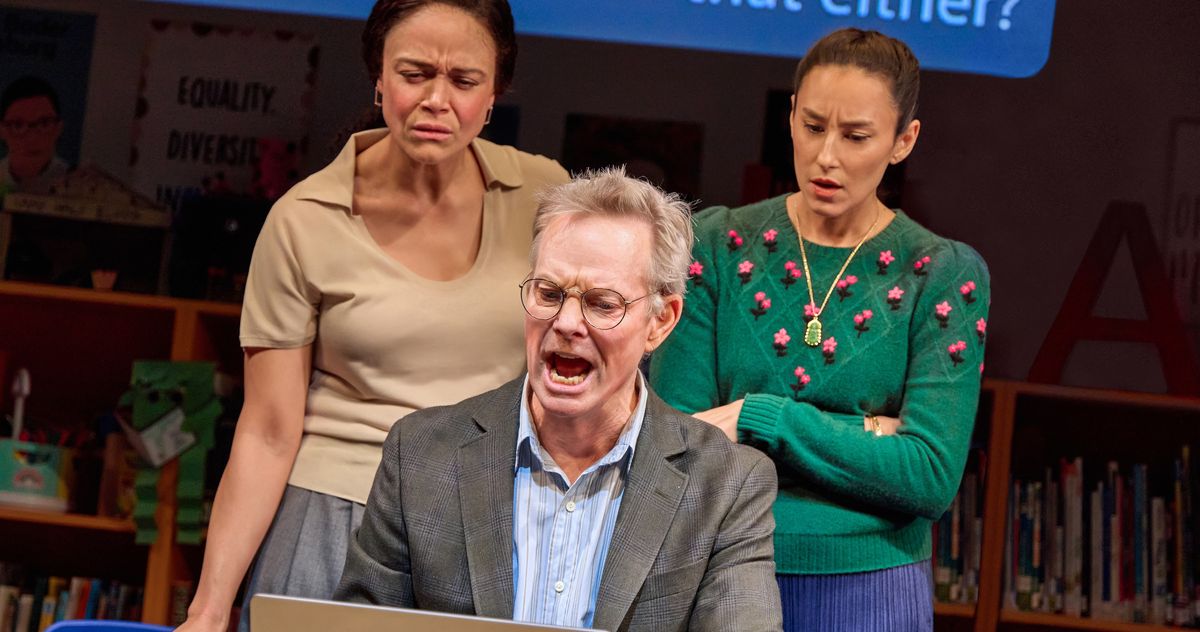

From Eureka Day, at the Friedman.

Photo: Jeremy Daniel.

Muhammad Ali might be proud of Jonathan Spector, whose Eureka Day starts with a flutter and turns on a nasty sting. It’s no spoiler to talk about that eventual gut punch; even before it comes, much of the play’s floating and dodging is laced with peril. The show is a polite tiptoe along a cliff, a trek across a field of eggshells that as often as not are strewn atop landmines. Spector has a keen ear for the particular dialect adopted by liberal communities in the aftermath of the first Trump election. For many at this point, it’s a cringily familiar patter: soft-spoken, high-strung, defensive, apologetic, riddled with anxiety. A messy blend of earnestly caring and desperately attempting to perform that care. The terrified dance of the well-intentioned.

And oh, how the characters of Eureka Day dance. They are members of the executive committee at the titular academy, a private elementary school in the Berkeley Hills. They bring artisanal scones to their meetings in the school’s sunny library, where the Social Justice section is front and center (and twice as big as Fiction) and the walls are adorned with posters of Michelle Obama and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. They operate according to bylaws that say all decisions must be reached by consensus (“it can lead to some very long meetings”), and they pepper their conversation with terms like “holding space,” “erasure,” “devalue,” and “other” and “impact” as verbs. “Our Core Operating Principle here is that everyone should Feel Seen by this community,” offers Eli (Thomas Middleditch), parent of Tobias and casually super-wealthy former tech bro, in a debate over whether the school should add “Transracial Adoptee” to the current options for race on its application. To which Suzanne (Jessica Hecht, light as a soap bubble and expertly unsettling) replies sweetly, “There’s no benefit in Feeling Seen if you’re simultaneously Being Othered, right?”

The Rumi-reciting Don (a subtly and wonderfully flustered Bill Irwin) might be head of school, and the committee might operate by unanimity, but it’s Suzanne who reigns, with a delicate fist in a locally-sourced alpaca-wool glove, when the play begins. Her many children have been through Eureka Day — they and the school are her life. She was there at its founding, when it was housed in an old church with an empty library. “So all of us, there were about fifteen families,” she tells Carina (Amber Gray), parent of Victor and, as a recent transplant to the Bay, the newest member of the committee, “we loaned all our books, everything age appropriate … which was a little sad at first, being home with no books, but also such a great practice to teach our kids, you know: Where does this object matter most?” Suzanne is empathetic and generous and passionately committed; she’s also a very well-off white woman who assumes that Carina’s family is on financial aid because she’s Black, and who repeatedly speaks for or past her fellow committee members. “I find the best way not to put words in someone’s mouth,” Meiko (Chelsea Yakura-Kurtz), parent of Olivia, tells Suzanne tartly as she looks down at her knitting, “is not to put words in their mouth.”

One gets the sense that even in relatively placid times, Eureka Day’s executive committee already wears each other out—and puts a strain on the local fancy scone supply—in navigating the day-to-day running of their little would-be utopia. Then, inevitably, into this uneasy peace, Spector drops a frag grenade. It’s early in the 2018–2019 school year, and a mumps outbreak hits Eureka Day. What would at first seem to be a medium-stakes situation, concerning but manageable, quickly snowballs into a full-blown catastrophe: “Wait,” types a parent into the Zoom comments thread when Don attempts to hold a digital town hall (sorry, “Community Activated Conversation”) about the outbreak, “HALF the school is antivaxxers? Seriously????”

At a swift 100 minutes, Spector’s play is hinged around its extraordinary third scene, in which the unholy debacle that eventually comes of the committee’s community Zoom meeting forms a kind of pinnacle for the action. There’s before unseen parent Arnold Filmore calls unseen parent Myla Townes an unspeakable name, and there’s after. Spector’s script is painstakingly scored here, with the increasingly incendiary comments thread, displayed above the actors in projections by David Bengali, running alongside the committee members’ dialogue with second-to-second precision. The audience response is another key element — so much of what’s dropped up there on the screen by the Zoom room is gaspingly funny (three cheers for Leslie Kaufman, the parent who only ever responds with a thumbs-up emoji) that the show’s actors often have to push right through waves of laughter. Thankfully, director Anna D. Shapiro trusts that chaotic overlap, heeding a script note by Spector that warns actors not to hold for laughs in this scene. It’s the right impulse — the comedy isn’t played at or played up. It spills out organically, messily, even upsettingly. For as much as we might laugh at the unfolding absurdity, it all contains the pang of familiarity, the dismal truth we’ve been learning every day for years now in our age of communication at a digital distance: We are infinitely more prone to cruelty from behind a screen. When you don’t have to look into someone’s eyes, saying “fuck you” is all too easy.

That’s why, even if many of us might think of Zoom as a post-2020 aspect of life, it fits so neatly into Spector’s play. Not only is it an ingenious device for expanding the scope of a story with a small cast; more important still, it makes us reckon with the difference between automatic online belligerence and the ache, the tedium, and the vital necessity of people actually talking to people. Though Spector’s stance on vaccination is clear—and there’s no reason for it not to be—none of his characters are broad satires. Suzanne and Carina are set up for the most contention, but even their simmering friction builds into a long private conversation in which Suzanne reveals the devastating personal history behind her mistrust. We may retain every ounce of our disagreement, but we can’t not see a human being, two human beings, struggling to reach each other across a chasm.

Hecht and Gray are excellent here and throughout, as is Shapiro’s whole company. They’re not clowning — though there’s a delightful wink of a moment in which Irwin’s Don waxes misty-eyed over the “actually quite subtle” mime work of a former colleague. Rather, they’re performing that crucial aspect of theater, its function as a space of civic practice, quite literally a place where we rehearse the hardest conversations, where we experiment with how to put together a community. In his script’s epigraph, Spector quotes from Eula Biss’s On Immunity, where Biss herself cites a doctor who describes a certain vaccine as “important … from a public health standpoint” but “not as critical from an individual point of view.” “In order for this to make sense,” writes Biss, “one must believe that individuals are not part of the public.” It’s this cognitive dissonance, so widespread and so clamorous and so tragically American, that theater, by its very nature, is always addressing, and in Eureka Day that essential refutation takes on explicit and eloquent form.

Eureka Day is at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.