This week’s science news featured a possible sign of life in a galaxy far, far away.

But don’t expect a visit from extraterrestrials anytime soon — the potential life-harboring planet, K2-18b, is located 124 light-years from Earth, and even if it does host life-forms, they would likely be little green microbes, not little green men.

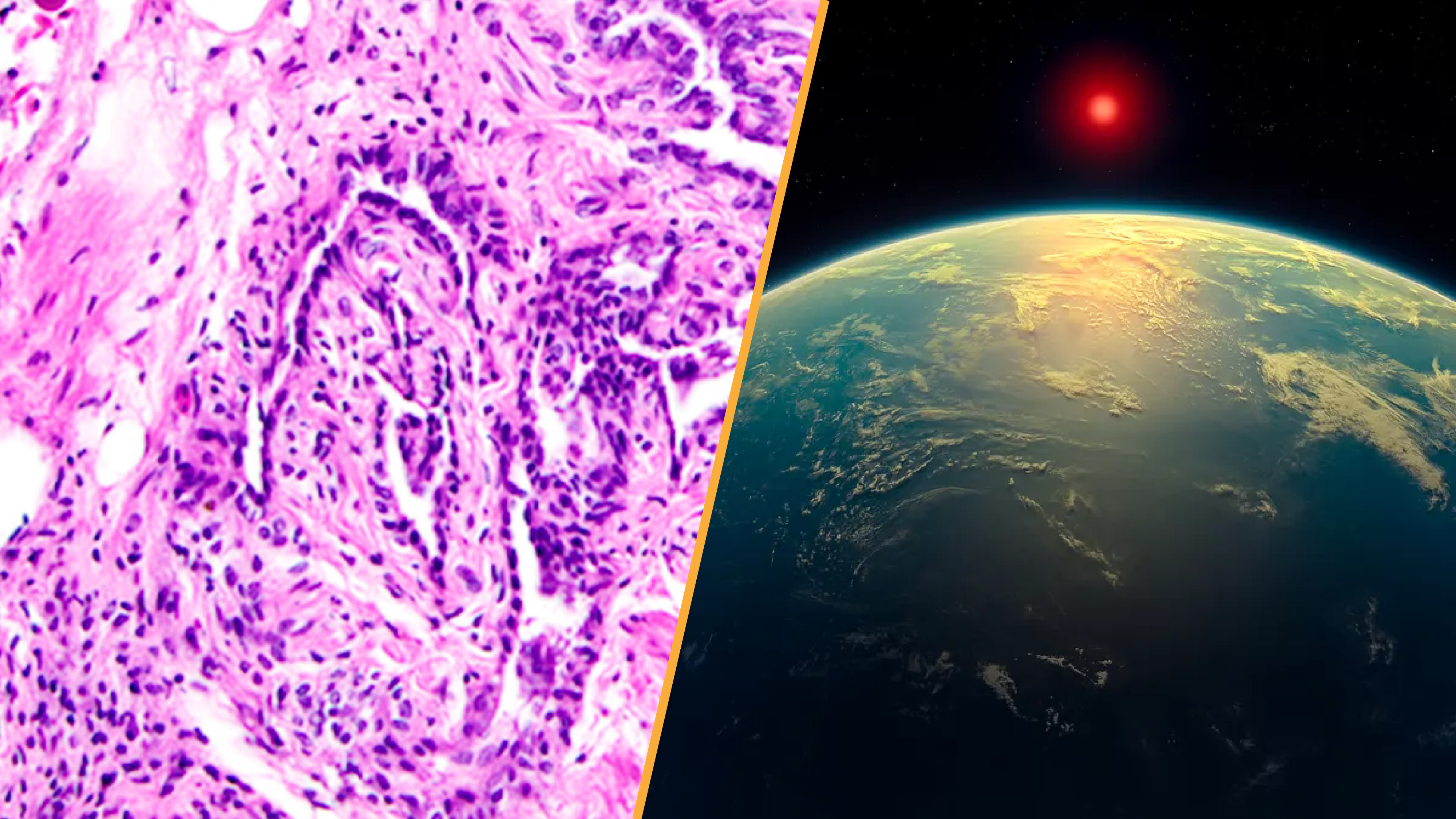

Scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) analyzed the chemistry of the distant planet’s atmosphere and found a large amount of two intriguing chemicals: dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and dimethyl disulfide (DMDS). On Earth, these chemicals are made only by certain microbes and algae, although, in theory, non-biological processes could make them, too.

This isn’t the first time JWST has studied this planet. Astronomers from the same team first trained the telescope on K2-18b because it orbits its star in the “habitable zone,” the distance from its star where liquid water could exist on the planet’s surface. K2-18b is thought to be a “Hycean” world with a water ocean and an atmosphere teeming with hydrogen.

In 2023, the team found methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere of K2-18b. These two chemicals can be produced by life but also by other processes. They also found hints of DMS and DMDS in the planet’s atmosphere at that time, but they didn’t have enough statistical certainty to be sure. So this time, they used a different instrument on JWST, called the Mid-Infrared Instrument, and detected a spike that could only be explained by these two chemicals.

“This is an independent line of evidence, using a different instrument than we did before and a different wavelength range of light, where there is no overlap with the previous observations,” study co-author Nikku Madhusudhan, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. “The signal came through strong and clear.”

It’s not quite proof of extraterrestrials — yet. The scientists showed the presence of DMS and DMDS with a statistical certainty of three sigma, meaning there’s a 0.3% chance it’s a statistical fluke. More measurements will be needed to reach five sigma, or less than a 0.00006% probability of occurring by chance. That’s the threshold typically used to confirm astronomical discoveries. They don’t have it yet, but that data could come soon, the researchers said.

Read more: Scientists reveal ‘most promising yet’ signs of alien life on planet K2-18b

‘Useless’ organ

It’s a tale as old as time: Doctors and scientists discover a new part of the human body, declare it “useless” and then forget about it for more than a century. But in a study published Thursday (April 17), researchers took a second look at one of these seemingly “vestigial” organs, called the rete ovarii (RO), and found it may play an unsung role in female fertility. The study was conducted in mice. However, the organ is found across mammals, so the researchers have reason to believe the results apply to humans.

The not-so-useless horseshoe-shaped structure is a bundle of small tubes that sits under the ovaries. In the new study, the researchers identified three distinct regions within the appendage and found that the structure may have receptors that bind sex hormones.

“There’s still so much we can’t even begin to comprehend about female anatomy,” study lead author Dilara Anbarci, a developmental biologist at the University of Michigan, told Science News. “I hope this encourages more investigation in reevaluating what we don’t already know about the ovary.”

Discover more health news

—‘Flesh-eating’ vulva infections reported in three cases — gynecologists should know the signs, experts warn

—Ozempic in a pill? New oral drug may work as well as Ozempic-style injectables

—100% fatal brain disease strikes 3 people in Oregon

Life’s Little Mysteries

Any time there’s a plane crash, investigators look for the “black box.” But what do these boxes actually record, and how do they tell us information about what caused a crash?

A ‘quiet Chernobyl’

Around 80 years ago, people diverted two rivers that flowed into the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan. It was an environmental catastrophe: The lake, once the world’s fourth largest, was hit by such a severe drought that much of it evaporated, and eventually, the shrinking lake split in two.

Research published this month quantified the effects of this “quiet Chernobyl” disaster and found that it eliminated 1.1 billion tons (1 billion metric tons) of water — enough that the Earth beneath it rebounded “like a compressed spring that has been released,” Simon Lamb, an associate professor of Earth science at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, wrote in an article published alongside the study in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The effects of that rebound are still being felt today as the earth around the lake continues to recoil, the researchers found.

Discover more planet Earth news

—An ocean of magma formed early in Earth’s history, and it may still influence our planet today, study finds

—Why is this desert turning green? Scientists may finally know the answer.

—The North Pole could wander nearly 90 feet west by the end of the century

Also in science news this week

—Stone Age tombs for Irish royalty aren’t what they seem, new DNA analysis reveals

—Scientists may have finally found where the ‘missing half’ of the universe’s matter is hiding

—Scientists reveal signs of crucial life-sustaining process on Mars: ‘I knew right away how important this discovery was’

—Massive circular tomb filled with battle-scarred people unearthed in Peru

—US company to use giant spinning cannon to blast hundreds of pancake-like ‘microsatellites’ into space

A 100-year sun cycle discovered

For centuries, we’ve known that the sun goes through an 11-year cycle of lower and higher activity as its magnetic field flips. During periods of solar minimum — when its activity is lowest — all is relatively calm on the surface of our home star. Then, solar activity ramps up, and the sun spits out fiery blobs of plasma and solar wind as it ramps up to solar maximum.

We have just entered a new phase of solar maximum. But the intensity of this solar maximum has led some researchers to propose that another, 100-year cycle may also be affecting the sun’s activity. This lesser-known cycle, called the Centennial Gleissberg Cycle (CGC), modulates the intensity of sunspot cycles every 80 to 100 years.

It’s not clear why the CGC happens, but it may be due to a “subtle sloshing” of the sun’s magnetic fields that, in turn, affects another sun cycle, Scott McIntosh, a solar physicist at the newly formed space weather solutions company Lynker Space who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

If that’s the case, then we could be in for much more vibrant auroras for decades to come — and our space communications could be in more peril than we suspected. But not everyone agrees that the CGC is turning over. McIntosh said it’s too early to make that conclusion, and other experts are skeptical, as well.

Something for the weekend

Something for the weekend

If you’re looking for something a little longer to read over the weekend, here are some of the best long reads, book excerpts and interviews published this week.

—Two planets will form a ‘smiley face’ with the moon on April 25. Here’s where to look. (Skywatching)

—Primates: Facts about the group that includes humans, apes, monkeys and other close relatives (Fact file)

—‘The parasite was in the driver’s seat’: The zombie ants that die gruesome deaths fit for a horror movie (Book extract)

—‘A relationship that could horrify Darwin’: Mindy Weisberger on the skin-crawling reality of insect zombification (Interview)

Something for skywatchers

A meteor shower will light up the skies Monday night (April 21-22), bringing about 20 “shooting stars” per hour at the shower’s peak. It will be a great time to watch the spring spectacle; the waning crescent moon will be only 27% full, so the meteors will be bright against the relatively dark sky.

Science in motion

For the first time, scientists have captured live footage of the elusive, deep-dwelling colossal squid. Despite its name, the cephalopod was rather modest in size. A full century after the first specimen of this species was discovered, scientists with the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor captured footage of a juvenile measuring 11.8 inches (30 centimeters) long. The squid was swimming near the South Sandwich Islands at a depth of around 2,000 feet (600 meters) when the team’s remotely operated vehicle spotted the translucent baby navigating the abyss, its tentacles waving behind it.

Want more science news? Follow our Live Science WhatsApp Channel for the latest discoveries as they happen. It’s the best way to get our expert reporting on the go, but if you don’t use WhatsApp we’re also on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Flipboard, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky and LinkedIn.