Dozens of never-before-seen species of “extremophile” bacteria were hiding in a NASA clean room used to quarantine a Mars lander before it was successfully launched to the Red Planet more than 17 years ago, a new study reveals.

Some of the hardy microbes may be capable of surviving the vacuum of space. However, there is no evidence that the spacecraft or Mars were contaminated.

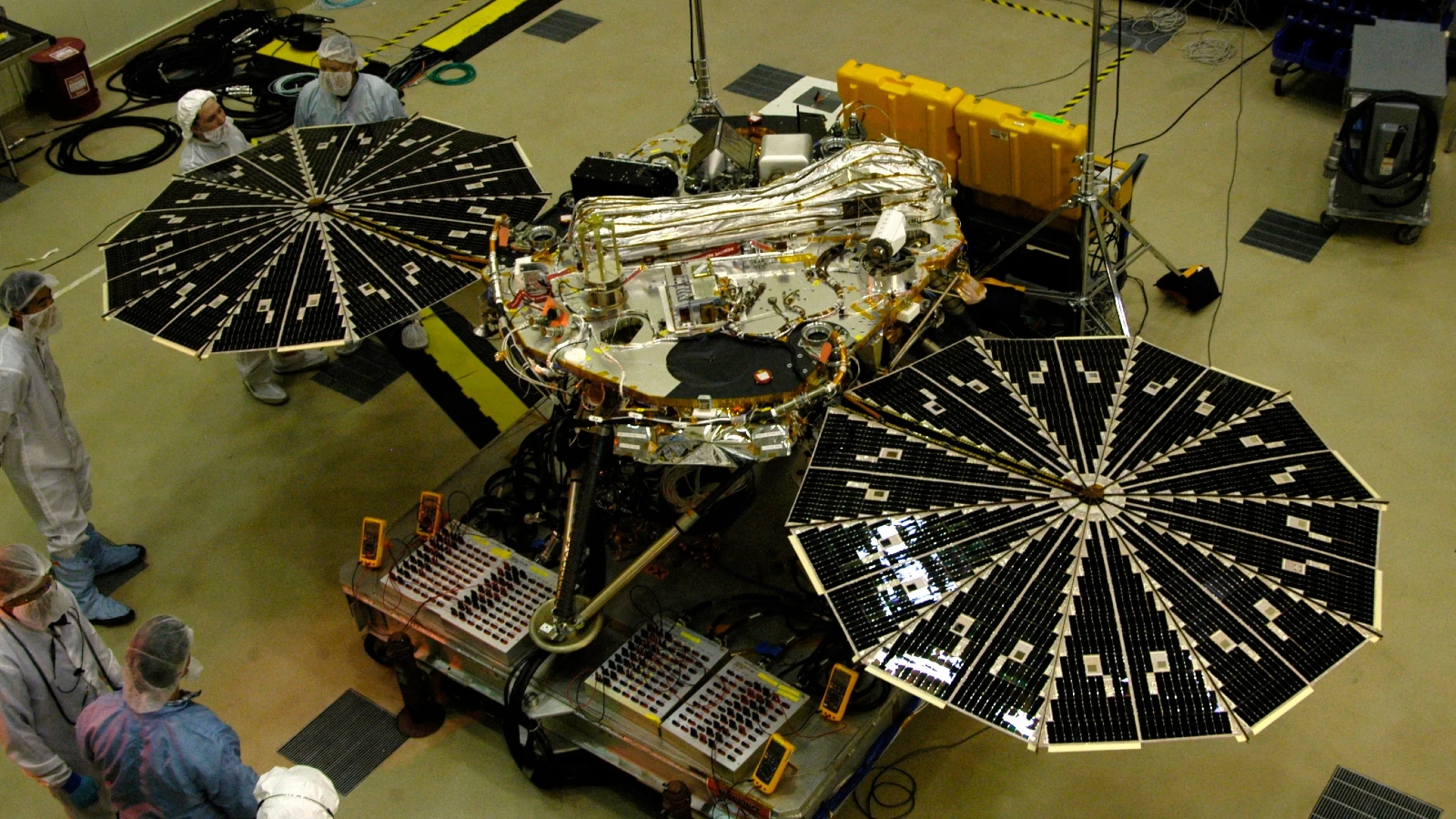

NASA’s Phoenix Mars lander touched down on the Red Planet on May 25, 2008, and spent 161 days (156 Martian days) collecting a variety of data, before suddenly going offline. Around 10 months before arriving on Mars, the lander spent several days inside a clean room at the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, before being launched from neighboring Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (then known as Cape Canaveral Air Force Station) on Aug. 4, 2007, according to Live Science’s sister site Space.com.

Clean rooms are spaces where spacecraft and their payloads are quarantined before launches and upon reentry to Earth, in order to prevent environmental contamination by microbes and keep them free of potentially damaging particles, according to NASA. These spaces are sterilized, pressurized, constantly vacuumed and supplied with air via special filters that keep out 99.97% of all airborne particles. Anybody entering the room must wear an all-in-one “bunny suit” and have an air shower before entering.

But all of these measures still can’t keep everything out. When researchers reanalyzed samples collected from the Phoenix lander clean room before, during and after the spacecraft was quarantined there, they found DNA from 26 novel species of bacteria. The team reported their findings in a study published May 12 in the journal Microbiome.

Related: Alien organisms could hitch a ride on our spacecraft and contaminate Earth, scientists warn

Most of the newly described microbes displayed at least some characteristics that made them resistant to harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, pressures and levels of radiation. Some had genes associated with DNA repair, detoxification of harmful molecules, and improved metabolism, and may even be able to survive the vacuum of space, the researchers wrote.

“Our study aimed to understand the risk of extremophiles being transferred in space missions and to identify which microorganisms might survive the harsh conditions of space,” study co-author Alexandre Rosado, a microbiologist at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, said in a statement. “This effort is pivotal for monitoring the risk of microbial contamination and safeguarding against unintentional colonization of exploring planets.”

The newly described species made up just under a quarter of all the species identified in the room, most of which also had extremophile properties. This suggests spacecraft clean rooms could be an excellent place to search for more of these hardy microbes.

Finding new extremophiles is important because it can help researchers predict what potential extraterrestrial microbes might look like and how we can prevent them from contaminating Earth. Some of them also produce substances, such as biofilms, that have potential applications in medicine, food preservation and biotechnologies.

“Together, we are unraveling the mysteries of microbes that withstand the extreme conditions of space — organisms with the potential to revolutionize the life sciences, bioengineering, and interplanetary exploration,” study co-author Kasthuri Venkateswaran, a retired senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in the statement.