A potent greenhouse gas has begun seeping out of the Antarctic seafloor in dozens of places, scientists have discovered.

Researchers documented the emergence of these methane seeps in shallow regions of the Ross Sea, a bay off the southern coast of Antarctica. The patches of leaking gas could be caused by global warming, and they could also threaten to accelerate it further, according to a new study published Oct. 1 in the journal Nature Communications.

“If they follow the behaviour of other global seep systems, there is the potential for rapid transfer of methane to the atmosphere from a source that is not currently factored into future climate change scenarios,” Seabrook added.

Methane (CH4) is a greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere by absorbing outgoing radiation. When methane first enters the atmosphere, it is a lot more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide (CO2), being about 80 times more potent across the first 20 years it’s in the atmosphere. This makes methane a particularly aggressive short-term driver of climate change. (CO2 stays in the atmosphere for longer, so it’s a more significant long-term driver.)

About 60% of methane emissions come from human activities such as farming and burning fossil fuels, while the remaining 40% come from natural sources. Scientists are concerned that as the planet gets warmer, more natural methane and carbon dioxide sources, such as those in melting permafrost, are being unlocked, creating a positive feedback loop that accelerates warming even further.

Researchers have previously spotted tens of thousands of methane leaks in the Arctic, but prior to the new study, there was only one confirmed Antarctic methane seep, identified in 2011. Underwater seeps create streams of bubbles as methane and other chemicals dissolve in ocean water following their release from beneath the seabed. White mats of microbial communities live around seeps, making them identifiable on the seafloor.

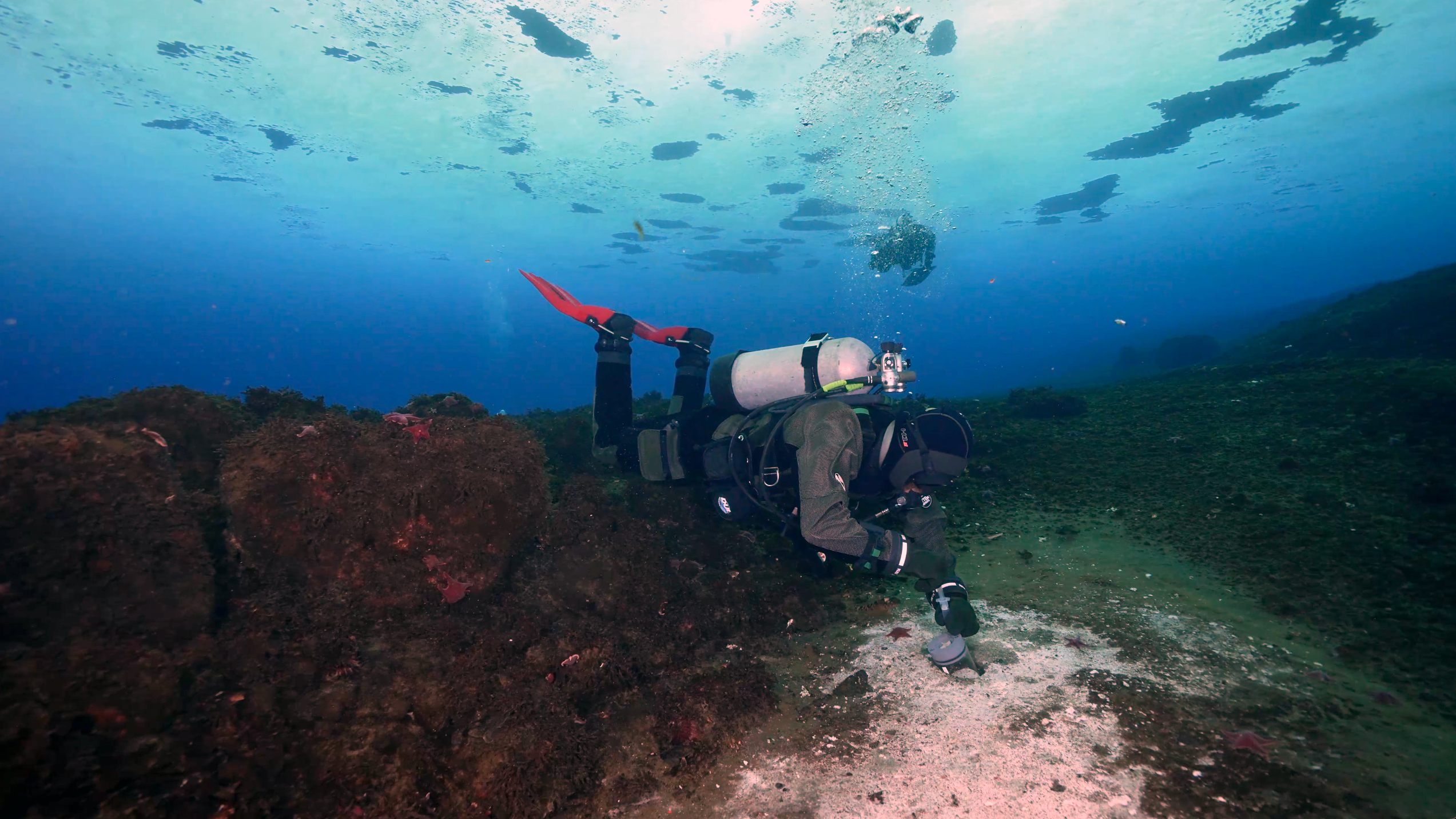

In the new study, researchers used acoustic surveys, divers and a remotely operated vehicle to explore seeps located between 16 feet (5 meters) and 787 feet (240 m) below the icy surface of the Ross Sea, off the Antarctic mainland. The team initially only went to investigate one seep in Cape Evans, located on the west side of Ross Island, and were surprised to find the seafloor littered with them.

“Last year, we went to Cape Evans to look at one small area where gas bubbles had been discovered and were hoping to find that one site still bubbling,” Seabrook said. “Instead, we found dozens more.”

The researchers studied areas that have been regularly surveyed for decades, meaning that the seeps must be a new feature. It’s not known exactly what is causing the seeps to appear, but the researchers noted that similar processes in the Arctic and paleorecord (past environments) have been attributed to climate-driven cryospheric change — the degradation of Earth’s ice that previously locked these chemicals in place.

It’s unclear how much methane might be leaving Antarctica and reaching our atmosphere, nor how much remains trapped beneath its thawing ice, but the researchers are concerned that the seeps could be widespread. This raises fears of positive feedback loops as well as a variety of other knock-on effects caused by methane, such as ocean acidification.

Seabrook and her colleagues recommended coordinated, international efforts to urgently study the seeps.

“If these seeps keep emerging at the areas we are working in, it really begs the question of what the shallow coastal environment of Antarctica may look like five or 10 years from now,” Seabrook said. “This system is rapidly changing before our eyes from one year to the next.”