Almost 2 million years ago, leopards likely hunted and feasted on our human ancestors in East Africa, a new study finds.

The research, which used artificial intelligence (AI) analysis tools, provides insight into the demise of two prehistoric individuals from the archaic human species Homo habilis — one of the earliest members of the Homo genus.

With the help of AI, however, a study published Sept. 16 in the journal Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences documents with “unprecedented reliability” the carnivore responsible for preying on the unfortunate H. habilis individuals.

“AI has opened new doors of understanding,” study co-author Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo, a professor of prehistory at the University of Alcalá in Spain and a visiting professor of anthropology at Rice University in Texas, said in a statement.

In the new study, Domínguez-Rodrigo and colleagues analyzed two H. habilis specimens: a juvenile (known as OH 7) and an adult (known as OH 65), dated to around 1.85 million years ago and 1.8 million years ago, respectively. Both specimens were found decades ago in the Olduvai Gorge site in Tanzania.

“We chose those two fossils because they are most unambiguously identified as H. habilis and because they are probably the best preserved specimens,” Domínguez-Rodrigo told Live Science in an email.

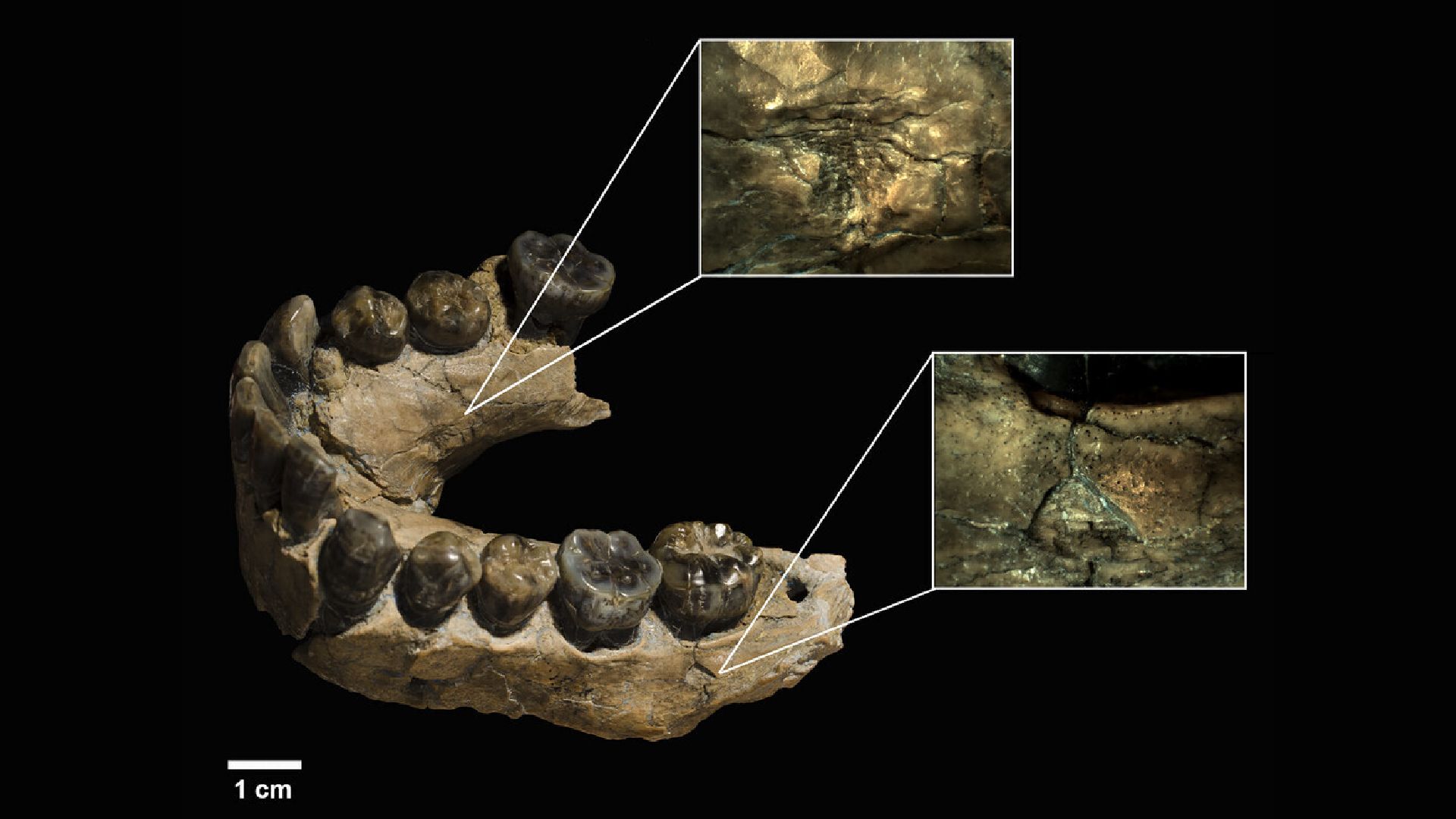

The team conducted a preliminary examination of the OH 7 and OH 65 specimens, identifying carnivore tooth marks on the upper jaw of the adult and the lower jaw of the juvenile, that had not been documented before. The team then applied AI tools to analyze these tooth marks.

Using computer vision — an AI technique for identifying items through images — the researchers trained deep learning models on hundreds of examples of bone markings produced by modern carnivores such as hyenas, crocodiles and leopards. In blind tests, the best of these models was more than 90% accurate in correctly identifying which animal produced the marks, according to Domínguez-Rodrigo.

Applying this system to analyze the OH 7 and OH 65 remains revealed, with a high degree of confidence, that the bite marks had been made by leopards, the study reported.

The conclusion that these H. habilis individuals were most likely preyed on and consumed by the leopards — rather than simply being attacked or bitten by them — is supported by several pieces of evidence.

“The fact that very few pieces of the skeleton survived indicates a high degree of ravaging,” Domínguez-Rodrigo said. “If a different carnivore had had access to habilis before the leopards, the latter would have been uninterested since they are only flesh-eaters,” he said, adding that in such a scenario, not much flesh would have survived in carcasses of this size after the first predator finished with its meal.

“We know that to reach the inside of the mandible [lower jaw] of OH7 (as the leopard did) and break the mandibular corpus, a substantial amount of flesh and tongue had to be removed first,” Domínguez-Rodrigo said. “This indicates consumption and not just a bite to kill.”