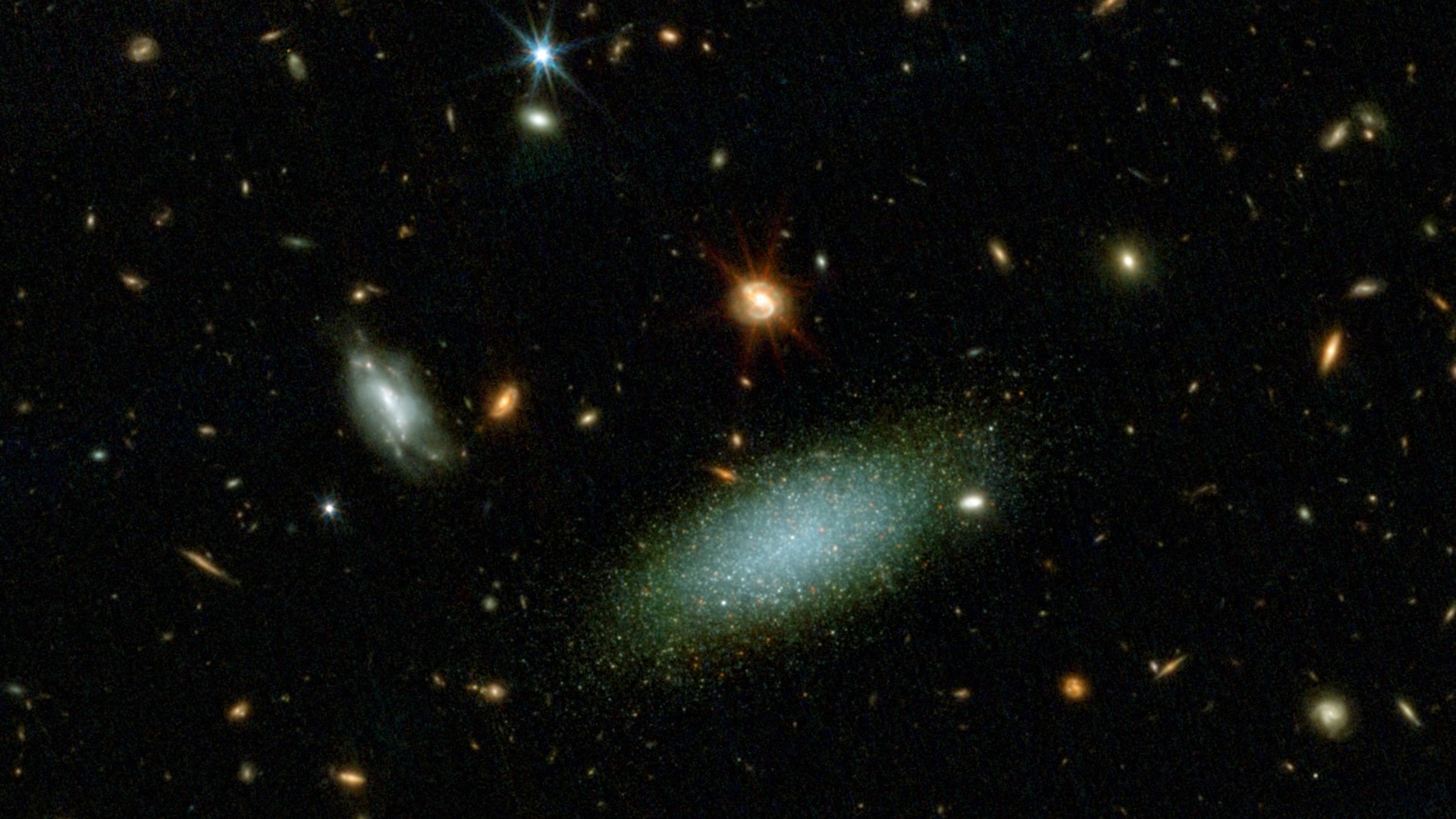

The oldest star chart in the world was made in China more than 2,300 years ago, a hotly debated preprint study finds.

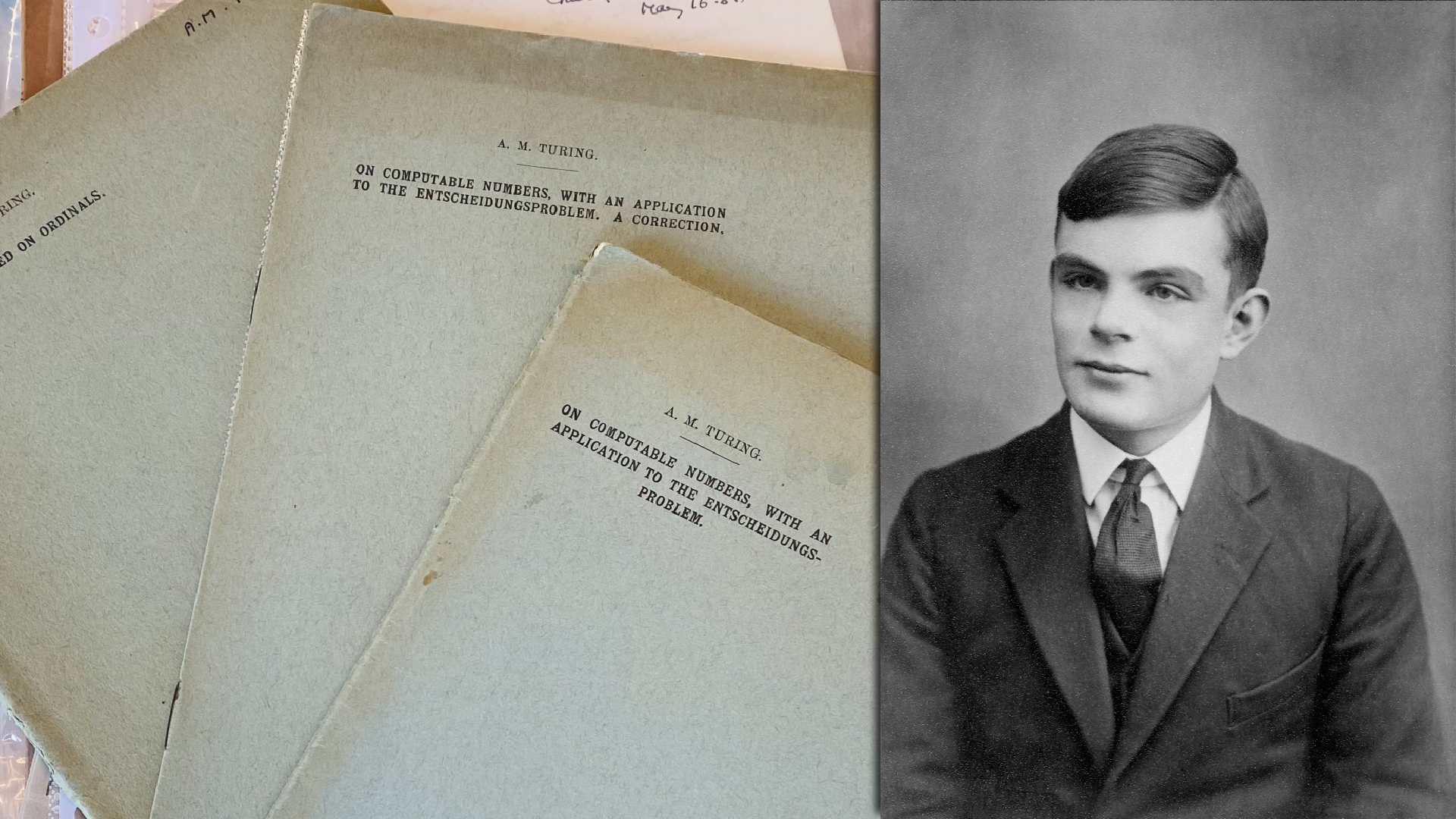

Researchers at the Chinese National Astronomical Observatories analyzed the “Star Manual of Master Shi,” the oldest surviving star catalog in China, using a novel digital image processing technique. The method, called Generalized Hough Transform, uses a type of artificial intelligence known as computer vision to find and mitigate significant errors between similar images.

They found that the ancient star chart actually dates to 355 B.C. — 250 years earlier than previously thought — and that it was later updated around A.D. 125. This would make it the oldest-known star catalog of its kind in the world, predating a star chart by ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus by more than 200 years.

“I think this is pretty definitive,”said David Pankenier, a professor emeritus of Chinese astronomy at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania who was not involved with the research. Pankenier told Live Science that the study confirms previous research — notably, the work of Joseph Needham, a British biochemist known for his expertise on ancient Chinese science and technology. And the new study places the manuscript’s origin around the same time the historical Master Shi Shen was thought to have lived.

But other experts are less convinced.

Related: World’s oldest complete star map, lost for millennia, found inside medieval manuscript

Historians and astronomers have long been puzzled by the alleged date discrepancies in Shi’s star catalog, in which some measurements seem to be hundreds of years older than others. Scientists can date star charts because, from Earth’s perspective, constellations appear to drift over hundreds of years because of the wobble in our planet’s axis. Stars also have their own motion, which means that different centuries will have different-looking maps of the night sky.

The new study chalks this discrepancy up to copying errors and partial updates, claiming that the manuscript was first created in the fourth century B.C. and then amended — sometimes inaccurately — hundreds of years later.

However, some experts not involved with the study instead suggest that the discrepancies exist because the original instrument used to create the manual was off by a factor of one degree.

Applying this interpretation brings the two seemingly conflicting sets of dates back into harmony and places the manuscript’s origin at around 103 B.C., Daniel Morgan, a historian who specializes in early Chinese astronomy, mathematics and metrology at France’s Center for Research on East Asian Civilizations, told Live Science. This reasoning also helps explain why the catalog uses a spherical coordinate system, which Chinese astronomers adopted after inventing the armillary sphere — a device consisting of interlocking rings representing things like constellations’ paths and latitude and longitude lines — in the first century B.C.

“It just so happens that if you take this really anodyne consideration into account — that maybe they built an instrument and it was not perfect — then the astronomers’ data analysis perfectly aligns with the human story,” Morgan said.

He pointed out that laying claim to the oldest star chart (or any other scientific tool) has become a source of national bragging rights over the last 300 years. Colonialism combined with decades of Eurocentrism have created a kind of “inter-civilizational … competition” whereby nations feel the need to prove themselves, he said.

But that same sense of national pride may have kept Western researchers from taking ancient Chinese astronomers seriously even as recently as 100 years ago, Pankenier said. Early 20th-century analyses of Chinese star charts by Europeans were dismissive of what they saw as inferior technology, even though many of these records proved highly accurate.

But regardless of whether scientists deem the Chinese or the Greek star catalogs as older, Babylonian records that mention star positions far outstrip both ancient Chinese and Greek astronomers, as they date to the eighth century B.C. However, these records are written descriptions and are not catalogs that number the stars and portray the night sky.

The preprint is currently under review at the journal Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics.