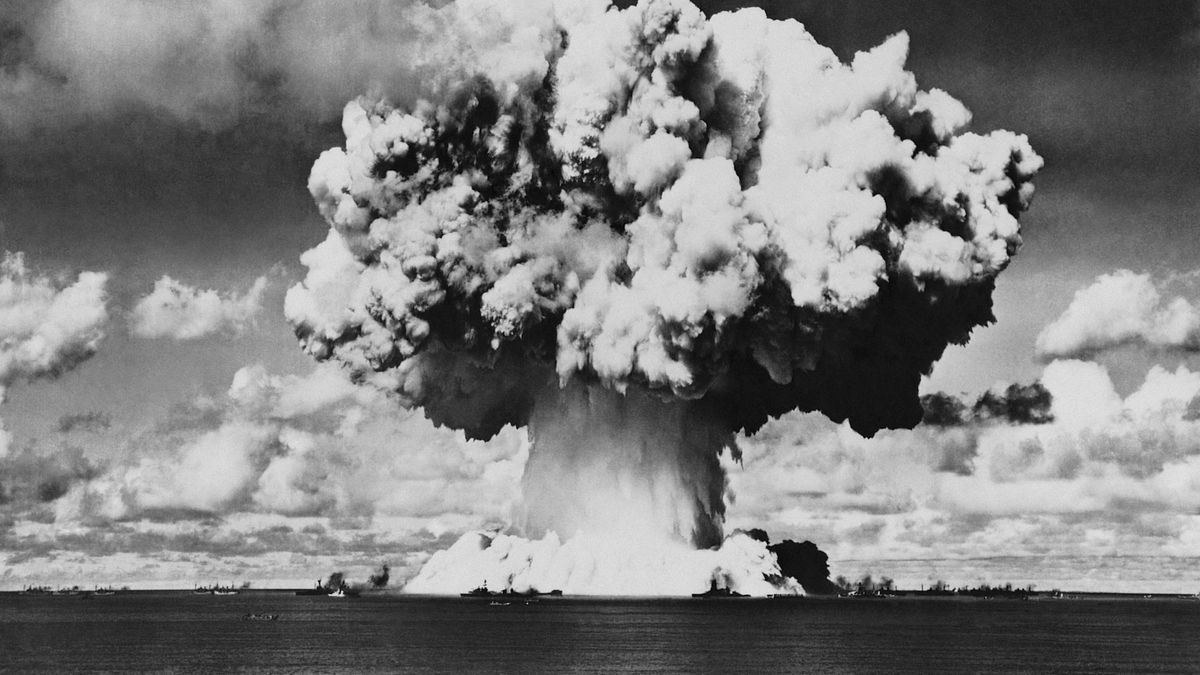

The first nuclear weapon test, code-named “Trinity,” took place in the New Mexico desert at 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945. This test was a proof of concept for the secret nuclear science taking place at Los Alamos as a part of the Manhattan Project during World War II and would lead to the atomic bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, just a few weeks later.

Since those detonations, the development of nuclear weapons has accelerated. Countries around the world have built their own nuclear stockpiles, including over 5,000 nuclear warheads held by the U.S.

Yet, even though the basic components of this technology are no longer secret, nuclear weapon development remains a scientific and engineering challenge. But why are nuclear weapons still so difficult to produce?

A big part of the difficulty comes from deriving the chemical elements used inside these weapons to create an explosion, Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, told Live Science in an email.

“That basic idea of a nuclear explosion is that nuclear [fissile] materials are stimulated to release their enormous energy,” he said. “To produce fissile material of sufficient purity and sufficient quantity is a challenge [and] this production requires considerable industrial capacity.”

Related: How many nuclear bombs have been used?

The enormous release of energy is called a nuclear fission reaction. When this reaction occurs, a chain reaction starts where the atoms are split apart to release energy. This is the same kind of reaction that makes nuclear energy possible.

Uranium and plutonium enrichment

The fissile material inside a nuclear bomb is primarily isotopes of uranium and plutonium, which are radioactive elements, Matthew Zerphy, a professor of practice in nuclear engineering at Penn State, told Live Science. Uranium’s most common isotope, uranium-238 (U-238), is mined and then goes through a process of enrichment to transform a portion into another isotope, uranium-235 (U-235), which can more readily be used in nuclear reactions.

“One way to enrich uranium is to turn it into a gas and spin it very rapidly in centrifuges,” Zerphy said. “Because of the difference in mass between U-235 and U-238, the isotopes are split, and you can separate out U-235.”

For weapons-grade uranium, 90% of a U-238 sample needs to be transformed into U-235, Zerphy said. The most challenging part of this process, which can take weeks to months, is the chemical transformation of the element itself, which requires intensive energy and specialized equipment. One chemical hazard during this process is the possible release of uranium hexafluoride (UF₆), a highly toxic substance that, if inhaled, can damage the kidneys, liver, lungs, brain, skin and eyes.

The process to enrich plutonium to the same degree is even trickier, he said, because this element does not occur naturally like uranium does. Instead, plutonium is a byproduct of nuclear reactors, which means to use plutonium, scientists need to handle radioactive, spent nuclear fuel and process the material through “intense” chemical deposition. The processing of this material can also pose a safety risk if a critical mass is collected accidentally, Zerphy said, which is the smallest amount of fissile material needed to sustain a self-sustaining fission reaction.

“You’d be very careful to not have that happen while you’re in the process of making these components to make sure that things aren’t inadvertently brought together and entering some kind of criticality,” he said, which could lead to an accidental explosion.

Related: Why did the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima leave shadows of people etched on sidewalks?

Although the scientific principles of bringing these components together is well understood, creating and controlling this reaction in a fraction of a second can still be difficult.

“The weapons are designed such that when they are detonated a ‘supercritical’ mass of fissile material is created very quickly … in a very small space,” Zerphy said. “This causes an exponential increase in the number of fissions spreading throughout the material almost instantaneously.”

This quick spread of atomic fission is a big part of what makes a nuclear reaction so destructive, he said.

In the case of thermonuclear weapons, which were developed after World War II and use a combination of both nuclear fission and fusion to create an even stronger explosion, a standard fission reaction then has to spark a secondary and stronger fusion reaction. This fusion reaction is the same kind of power found at the center of the sun.

Nuclear weapons testing

Once these weapons are created, scientists and engineers need to be sure the weapons will work as needed, should they ever be used. When nuclear weapons were first developed, scientists would test the weapons themselves at test sites (which devastated the environment of the “deserted” areas where they were tested, as well as people and animals that lived nearby). In contrast, modern weapon testing relies on computer models. This is part of the work done by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

“NNSA … develop[s] tools for qualifying weapon components and certifying weapons, ensuring their survivability and effectiveness in various scenarios,” an NNSA spokesperson told Live Science in an email. “This involves advanced simulations using supercomputing systems, materials science, and precision engineering to ensure weapons function as intended.”

Ultimately, the complexity and challenges of building these weapons may explain why so few nuclear superpowers exist in the world today.