From hunting prey to finding mates and avoiding predators, the ability to detect odors is crucial for survival in the animal kingdom.

But which species reigns supreme when it comes to smelling power? It turns out, that’s not such an easy question to answer.

There are approximately 5.8 million odor molecules and each of those odorants can be combined to create an almost infinite number of odor mixtures, Matthias Laska, a zoologist who specializes in sensory capabilities at Linköping University in Sweden, told Live Science in an email.

“Considering that only a tiny fraction of those odorants have been tested with any species so far, any generalizing statement about whether species A has ‘a better sense of smell’ than species B would simply be unscientific,” Laska said.

Part of the challenge in sniffing-out better smellers lies in how difficult it is to study olfaction in the first place. According to a book on the neuroscience of smell, “Olfaction in Animal Behaviour and Welfare” (CABI, 2017), olfactory research lags behind studies investigating vision, hearing, taste or touch. Unlike other sensory stimuli, odors are hard to control or measure — they disperse unpredictably, behave differently in air versus water, and vary greatly in chemical properties.

Still, researchers have found some intriguing clues as to which species might be the best smeller. One place to look is the number of olfactory receptor genes — the DNA sequences that code for proteins in the nose which bind to odor molecules.

Related: Can animals really smell fear in humans?

In a 2014 study published in the journal Genome Research, scientists counted the olfactory receptor genes in several species of mammal and found that African elephants had the highest number: a whopping 1,948. By comparison, humans have just 396 genes, dogs have 811 and rats have 1,207. This would make sense because elephants use their impressive sense of smell to locate food, recognize family members, detect predators and identify the short time window when a partner is ready to mate.

However, the genetic survey only compared 13 mammal species and did not include bears, who are anecdotally known to have a powerful sense of smell.

Another measure of an animal’s smelling ability may be the size of its olfactory bulb, the brain region responsible for processing odors. Dogs, which are famous for their scent-tracking skills, have significantly larger olfactory bulbs than humans, according to a 2011 comparative study published in the International Journal of Morphology. Among birds, turkey vultures top the list for a keen sense of smell, which helps the flying scavengers detect carcasses from great distances.

But does having a larger olfactory bulb actually translate into a stronger sense of smell? A 2011 review published in the journal Science pointed out that the number of neurons in the olfactory bulb is fairly consistent across species, regardless of the bulb’s size, which would undermine using size as a measure of olfactory capacity.

Smelling power can also be gauged by the ability to sense specific odors. One animal with an impressive sense is the African pouched rat, Tobias Ackels of the Sensory Dynamics and Behaviour Lab at the University of Bonn in Germany, told Live Science in an email. “These rats can be trained to detect landmines and have been used to sniff out tuberculosis in human patients using their sense of smell.”

Beyond the world of vertebrates, male silk moths might take the crown. “Moths are smelling champions when it comes to sensitivity,” Gabriella Wolff, a neuroethologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, told Live Science in an email. Male moths can find mates located up to 2.8 miles (4.5 kilometers) away by detecting female pheromone chemicals. “In some cases, a male can detect a female from a single pheromone molecule,” Wolff said.You can’t get any more sensitive than that!”

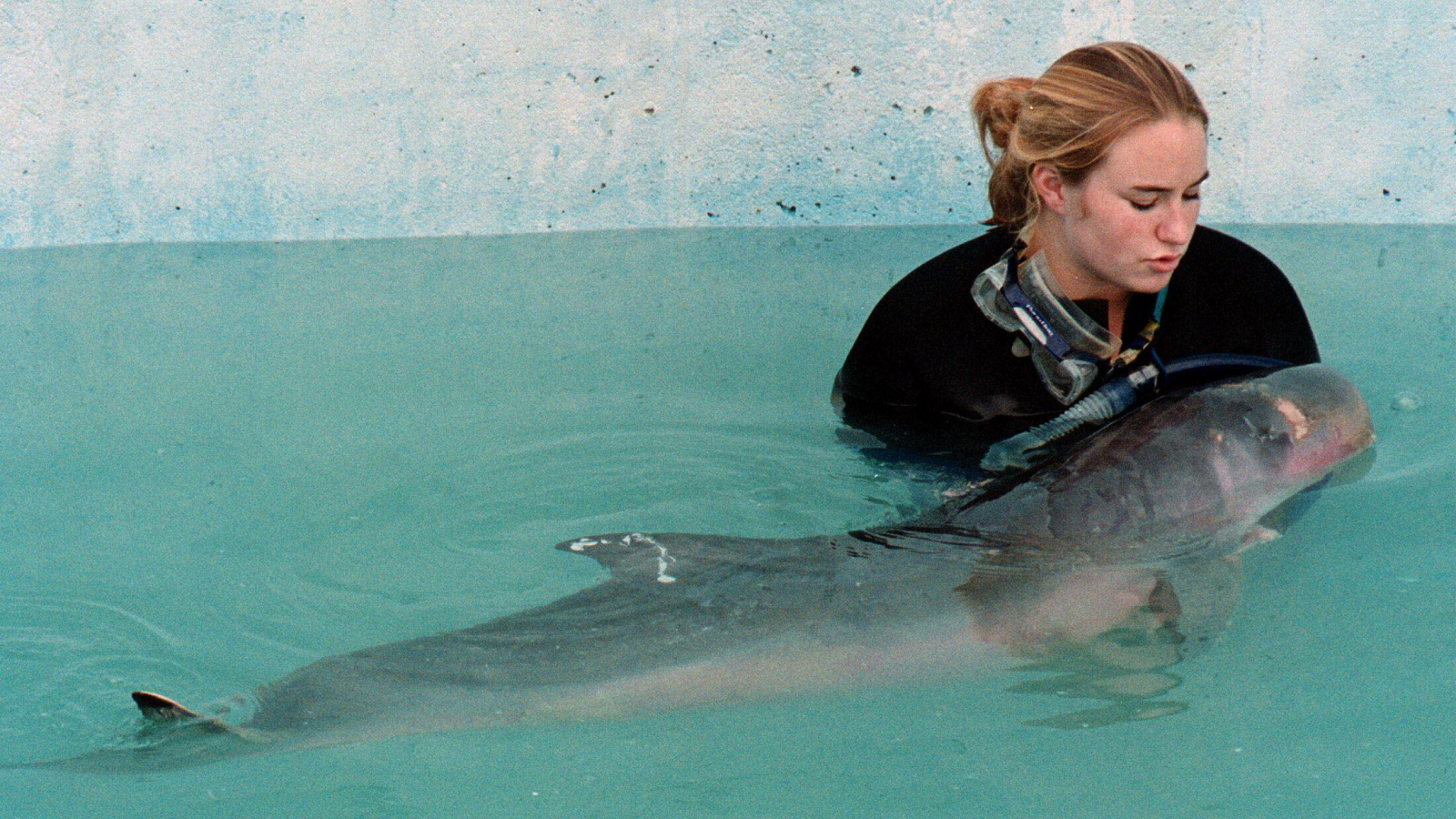

Sharks have an exceptionally keen sense of smell — far more sensitive than that of humans — which is important for hunting and mating. While some species can detect chemicals in water at concentrations as low as one part per 10 billion, the popular claim that they can smell a single drop of blood in the ocean is a myth, according to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Although humans have far fewer smell receptors than dogs, they are better at sniffing out certain fruit-related odors. These odors are “behaviorally irrelevant to a carnivore such as the dog, but presumably behaviorally relevant for us primates,” Laska explained. This leads him to believe that an animal’s ability to smell a particular odor is dictated more by the behavioral relevance of that odor than by its neuroanatomy or genetic makeup.

Ackels puts it another way. “Rather than naming a single ‘champion smeller’, it’s more accurate to say that different animals are specialists, each with a sense of smell shaped by their ecological niche.”