Nearly a billion light-years away, a massive spiral galaxy is screaming into the void.

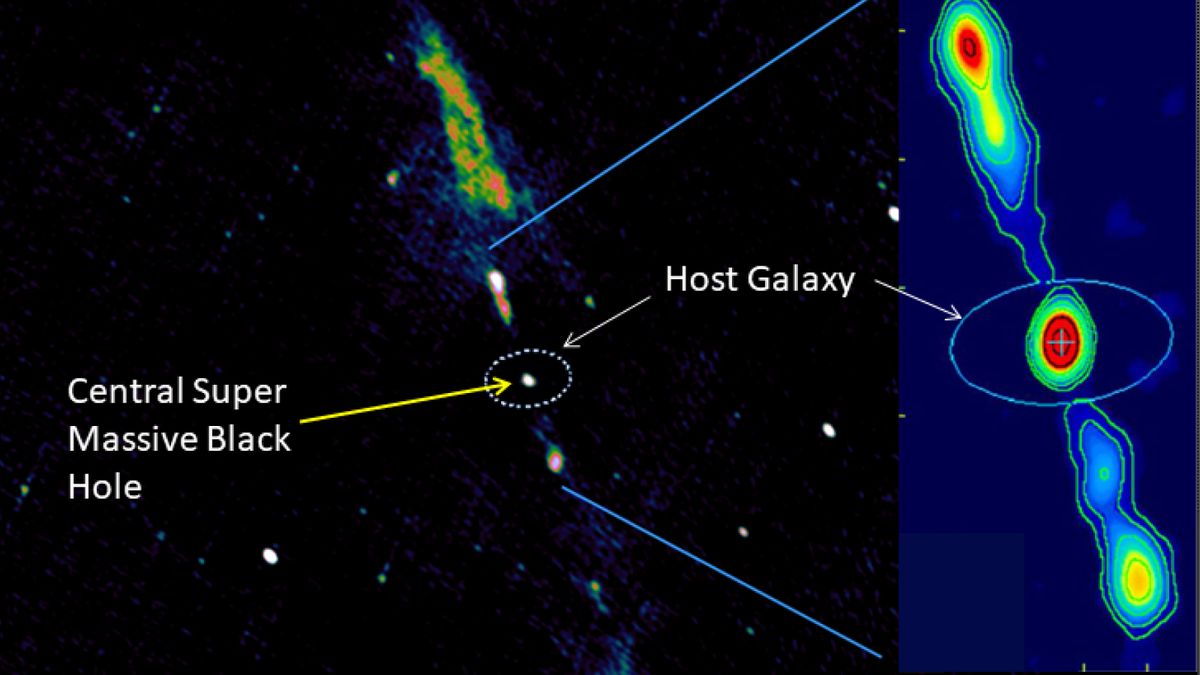

The behemoth, nicknamed J2345-0449, is a giant radio galaxy, or “super spiral” galaxy roughly three times the size of the Milky Way. Like our own spiral galaxy, it harbors a supermassive black hole at its center. But unlike the Milky Way’s center, J2345-0449’s supermassive black hole emits powerful radio jets — streams of fast-moving charged particles that emit radio waves — stretching more than 5 million light-years long.

Though scientists don’t yet know what fuels the radio jets, a new study, published March 20 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, hints at how giant spiral galaxies could form.

Such strong radio jets are “very rare for spiral galaxies,” Patrick Ogle, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. “In general, they can have weak radio jets, but these powerful radio jets typically come from massive elliptical galaxies. The thought behind that is that to power these really big jets requires a very massive black hole, and one that’s probably also spinning. So most spiral galaxies don’t have massive enough black holes in the centers to create big jets like this.”

Related: Supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way is approaching the cosmic speed limit, dragging space-time along with it

Data from the Hubble Space Telescope, the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope, and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array suggest that the radio jets currently prevent stars from forming near the galaxy’s center. That’s likely because the jets heat up nearby gases so much that they can’t collapse into new stars — or push them out of the galaxy entirely.

Jets in our neighborhood?

Though both J2345-0449 and the Milky Way are spiral galaxies, it’s unlikely that we’ll observe these powerful jets in our galactic hometown.

“This galaxy is so different from the Milky Way,” Ogle said. “It’s a lot bigger, and the black hole is a lot more massive.”

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, is likely too small to produce radio jets as powerful as the ones observed in J2345-0449, Ogle told Live Science. Still, studying these rare galaxies could help scientists understand how the growth of supermassive black holes and of their host galaxies are related. Based on the shape of the group of stars at the center of the galaxy, it’s possible that this black hole and its massive host galaxy have grown together in relative isolation, rather than gaining their mass from galaxy mergers.

In the future, detailed studies of the galaxy’s supermassive black hole could also explain what powers its massive radio jets. “The extreme rarity of such galaxies implies that whatever physical process had created such huge radio jets in J2345-0449 must be very difficult to realize and maintain for long periods of time in most other spiral/disc galaxies,” the researchers wrote in the study.

“Understanding these rare galaxies could provide vital clues about the unseen forces governing the universe,” study co-author Shankar Ray, an astrophysicist at Christ University, Bangalore, said in a statement. “Ultimately, this study brings us one step closer to unravelling the mysteries of the cosmos, reminding us that the universe still holds surprises beyond our imagination.”

Black hole quiz: How supermassive is your knowledge of the universe?