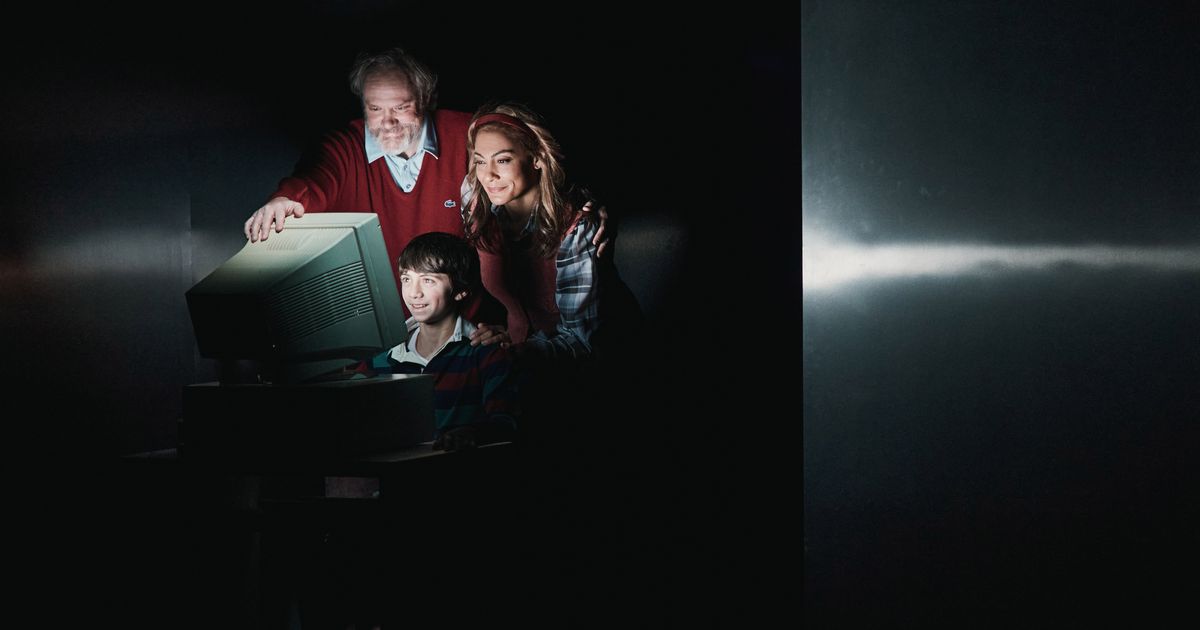

From The Antiquities, at Playwrights Horizons.

Photo: Emilio Madrid

In Jordan Harrison’s telling, the beginning of the end, in terms of humanity’s relationship with the machines, may lie at the point where we start ascribing to them a personality. It’s not just that Siri, or Alexa, or Gemini, or whatever other femme-neutral name Silicon Valley applies to its latest robot helper can put together a grocery list for you — it’s that you have started to imagine that she has some distinct outlook on the universe. In one scene in Harrison’s drama The Antiquities, a trio of tech bros listens to a series of voice samples for a Google Home–esque product they are designing named Robyn. The phrase “Where to now? You’re the boss” gets repeated over and over as they bicker about how each iteration might fare in the marketplace. Each voice lends the thing a persona. A British one is deemed too Mary Poppins. Their goal, the guys insist, is something that feels like “a member of the family.”

The scene takes place in 2014, well away from the singularity of robot sentience, but at that point in Harrison’s compressed yet expansive drama, the idea of an artificial intelligence ingratiating itself into a human family already feels eerie. That’s because, at the top of Harrison’s play, we learn that the robots have won and we’ve lost, if such terms even apply. Those of us in the audience are told that we are AI beings, stopping in for, as the play’s full title reads, A Tour of the Permanent Collection in the Museum of Late Human Antiquities. The robots are doing the archaeology on where humans went wrong, or maybe just trying to understand how the humans are different. After a chipper and yet cool—probably just the right tone for Robyn — introduction from the two women hosts of the museum (Kristen Sieh and Amelia Workman), the play skips back to the 19th century, where we see Mary Shelley among her fellow Romantics in Lake Geneva dreaming up Frankenstein. It’s an early milepost in humans’ seizure of the fire of creation for themselves (it goes unmentioned onstage, but you may think of the book’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus). From there, Harrison telescopes forward in time via a series of vignettes, as actors take on multiple roles across the years. Like a rock skipping across a lake, we touch down with factory employees in the early 20th century and a computer programmer in the 1970s, up through the Y2K-era rise of the internet and those bumbling-but-maybe-not 2010s tech bros. Then the exhibit barrels forward into our putative downfall, as machine learning starts to replace acting and writing (seen in an unnerving Hollywood conversation in 2031), and then sets its sights on eradicating us messy flesh beings altogether.

While the future that Harrison lays out before us might seem both grim and plausible, the production, under the direction of David Cromer and Caitlin Sullivan, takes a mile-high view of the end of the species. There’s little rage to be found, rather more of a precision-honed penumbral melancholy of the kind at which Cromer excels, whether in The Band’s Visit or A Case for the Existence of God, here tinged with absurdity—fitting, maybe, that over at Clubbed Thumb a few seasons back, I’d seen Sullivan direct a kindred, but more Dada take on tech in WORK HARD HAVE FUN MAKE HISTORY. That mood is enhanced by Paul Steinberg’s spare, reflective set and the pinprick quality of Tyler Micoleau’s lighting, which makes it feel as if you’re watching everything in one of those cardboard-and-aluminum-foil boxes you build in school to view an eclipse. The tone is in keeping with the conceit — here, the robots gaze back on us with bemusement and pity — though, given that we’re talking about human extinction, the tone can slip past ruminative and generous toward complacency. A few of Harrison’s characters rebel against the robots, whereas others make a kind of peace with them. The levers of corporate influence appear, as in one scene where a woman is pressured to take a deal with a Big Tech firm to buy her silence about the sentience of their product. But the pressure exerted by capital to accept inferior products, and to swallow the ecological impact of language-learning models as they exist currently, is left on the wayside in favor of asking us to think about AI in terms of parents and children. It’s a cleaner, gentler, metaphorical register: Harrison has speculated on similar themes of robotic intelligence in his Pulitzer finalist, Marjorie Prime, a play that might be called a smartphone-enabled kitchen-sink drama. But as he’s expanded his purview from a family drama to a century-spanning epic, Harrison’s conclusions have gotten more pat, too neatly in the zone of college philosophy class. I could really go for a more skeptical look on who asks us to swallow tech advances and why.

The Antiquities traverses those centuries over the course of a single intermission-less stretch. Condensed as that may feel, it comes in some fine packaging. This is a tripartite production of Playwrights Horizons, Vineyard Theater, and the Goodman, and the ace ensemble includes Cindy Cheung, Marchánt Davis, Layan Elwazani, Andrew Garman, Julius Rinzel, Aria Shaghasemi, Kristen Sieh, Ryan Spahn, and Amelia Workman. It would take too much time to identify and praise the various performances; almost everyone gets a turn in the spotlight, as well as another secondary role that provides a counterpoint. Cheung, for instance, lends her invaluable comedic timing to a laconic factory worker and then is brittle and heartbreaking as a mother mourning a tech-wiz daughter. Spahn is gently sweet as a closeted computer programmer and then a 2010s Soylent doofus. When Harrison zooms all the way into the specifics of a scene, especially in those vignettes with Cheung’s mother and Spahn’s coder, his work sings most cleanly, where naturalism melds with sly wit. You will not forget watching a blowjob happen in front of a robot prototype. When The Antiquities reaches further afield, Harrison falls back on well-used sci-fi tropes. It is hard to render characters churning butter after the apocalypse while talking in unsophisticated English without it coming off a little silly — recall any number of movies and TV shows. When the rebels are in cloaks and beanies, you may feel you’ve seen this kind of postapocalyptic knitwear before, especially in something like the Wachowskis’ Cloud Atlas.

The latter work, intentionally or not, looms over this drama with its similar structure and similarly chest-thumping-yet-vague humanism. The Antiquities even follows the novel’s Russian nesting-doll format, introducing half of each story line as it moves from the past to the future, and then reversing course and unveiling the second half of each exhibit in reverse, all of it heading back toward Frankenstein. In that sequence, Harrison ties together many of the play’s themes, especially its essential emphasis on how these machines were created to fill the space of a human need for family. The characters emerge as nervous parents and wounded children, disconnected from each other, ladling the energy they can’t adequately channel into human connection instead into these objects, physical or entirely electronic, a coder’s prototype robot, a daughter’s web blog, a grandfather’s voice-mail message. Harrison’s take on the difference between the 1s and 0s of machine learning and the emotional fallibility of human reasoning is something familiar, but this focus on objects did stick with me. In the middle of the forward-and-back drama, Harrison reveals his museum’s collection of those titular antiquities: Those AI curators have put everything from a teddy bear to a Warriors T-shirt on display, and in some cases misunderstood their use. The gesture is implicitly wry — Look, there are things about us the machines will never grasp — and yet hopeful. Whatever follows after us will see the things we left behind and try, as we did, to breathe life into them too.

The Antiquities is at Playwrights Horizons through February 23.