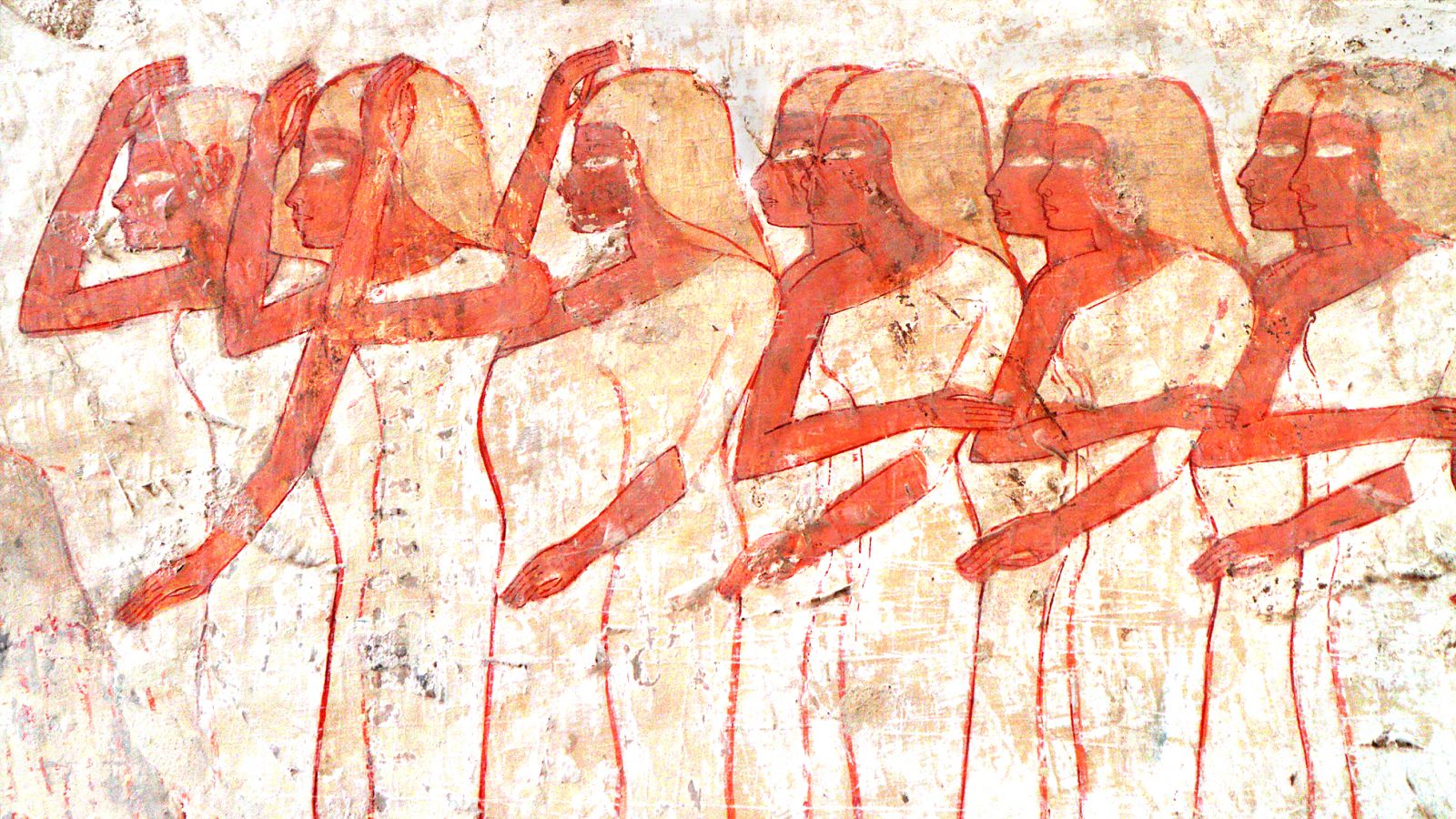

As humans evolved, our heads got bigger and walking upright narrowed the birth canal — a difficult and dangerous combination that means, in most cases, we need assistance in giving birth, from emotional support to intervention, as well as medical support for life-threatening conditions such as high blood pressure, uterine rupture and postpartum hemorrhage. Before written records, we see depictions of pregnancy and fertility, but little is known of how pregnancy and childbirth were viewed and treated.

In this excerpt from “Born: A History of Childbirth” (Pegasus Books, 2025), author and historian Lucy Inglis reveals records from ancient Egypt that show how female physicians treated issues of “the womb,” how men reacted to periods, and how the first known pregnancy test actually worked.

There is one female physician who lived during the building of the great pyramids, around 2500 B.C., who we know about because her name and profession were recorded on her son’s tomb door in Saqqara: Peseshet, the Overseer of Female Physicians.

Women like Peseshet were not the local wise women but respected professionals. Her son Akhethotep was a royal official, so his mother was firmly embedded in the literate elite classes. The tomb door, however, leaves us with as many questions as it does answers.

Who were the female physicians she oversaw? Who and what did they treat? The “professional” middle class of Peseshet and the tattooed priestess also left the world’s first specific gynaecological text, the “Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus”, which dates from 1825 B.C.. It contains 34 paragraphs of advice that most doctors today would not recommend following, and it diagnoses almost every female complaint as being that of “the womb.”

The examination of a woman “whose eyes are aching till she cannot see, on top of aches in her neck,” which sounds like a migraine, leads to the conclusion that she must have “discharges of the womb in her eyes.” This is treated by “fumigating her with incense and fresh oil, fumigating her womb with it, and fumigating her eyes with goose leg fat. You should have her eat a fresh ass’ liver.”

While fumigating her womb can’t have helped, perhaps the liver at least provided some welcome nutrition.

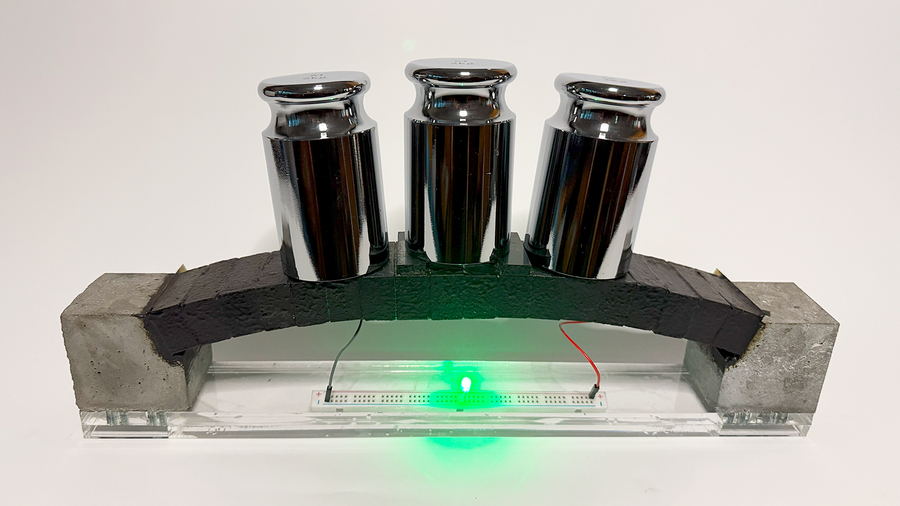

Only one examination, which sounds like a prolapse, correctly points to genuine involvement of the womb itself. It is treated by the pouring of oil, although on which part of the body is not identified. The papyrus also recommends putting a clove of garlic in your vagina before bed, and if your breath smells of garlic the next morning, it means well for the pregnancy. If not, it bodes ill.

The papyrus is also notable, however, for the first use of the term “wandering womb,” a term that would haunt women in various guises for another two millennia. The immaculate record-keeping of the workers of Deir el-Medina also includes intriguing entries for absence known as hsmn, meaning menstruation.

A set of tablets written in the reign of Ramses II cover a 280-day period in which 10 prominent workmen took “sick days” owing to hsmn. As men do not menstruate, this is something of a puzzle. The meaning is clarified, however, by the scribe Qenhikhopshef’s fuller entry for Day 23 — he was absent due to his wife “having her menses.” That winter the foreman of the works, Neferhotep, also took time off for his daughter’s period.

Historians over the past century concluded that this must mean that the Egyptians thought that the menstruating body was “unclean,” but this is just speculation. There are ancient Nubian customs still found in modern Ethiopia and Sudan which warn that menstruating or pregnant women should not enter cemeteries. Perhaps it was not the women who were unclean but the workers.

Rather than fearing that the husband of a menstruating woman might bring pollution to the sacred Valley of the Kings, the male workers may have been asserting their right not to “take their work home with them.” To do so might have brought death into their homes at a time when the women in their family were vulnerable.

The elites of any society leave monuments, art and literature behind for us to find that aim to portray their patrons as somewhat superhuman, but the poor rarely leave any trace of their existence at all. It is only relatively recently that their lives began to be recorded for statistical purposes. So it is no surprise that it is from the written records of the middle classes of ancient Egypt that we learn about the first known pregnancy test, written around 1350 B.C., in the medical text known as the Berlin Papyrus.

It states: “Barley [and] wheat, let the woman water [them] with her urine every day with dates [and] the sand, in two bags. If they [both] grow, she will bear. If the barley grows, it means a male child. If the wheat grows, it means a female child. If both do not grow, she will not bear at all.”

Remarkably, this theory was tested in 1963 and found to be accurate in 70% of cases, although the success of gender determination was not recorded. The tests have even been repeated subsequently at various intervals up until 2018 and have correctly identified 70–85% of pregnant participants.

Excerpt from Born: A History of Childbirth by Lucy Inglis. Published by Pegasus Books on October 7, 2025.