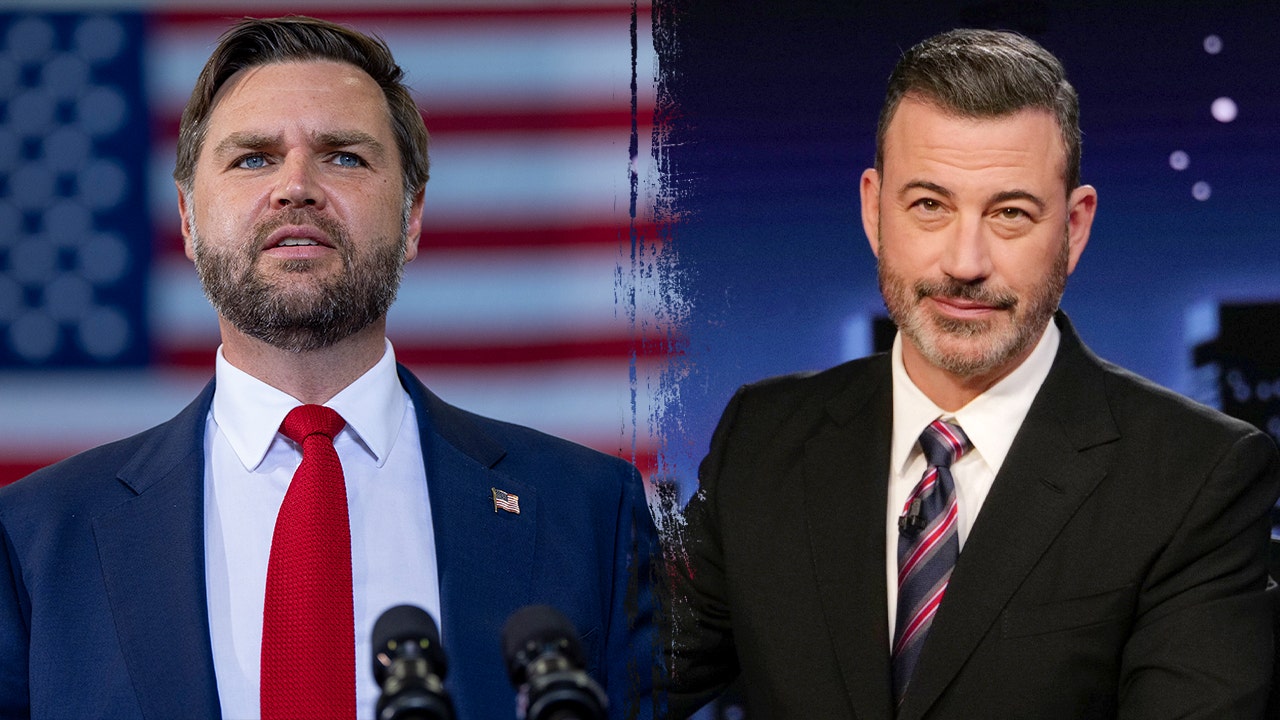

John Leguizamo and Luna Lauren Velez in The Other Americans.

Photo: Joan Marcus

On the way out of The Other Americans, the new drama written by and starring John Leguizamo, I overheard a man about my age talking to his friend as they shuffled up the aisle. “If that isn’t my family,” he said, trailing off. He looked a little shell-shocked. I don’t know what he thought of the play as a play, but he had seen something of his own experience on stage and it had moved him.

Sadly, that’s probably the only way anyone seeing Leguizamo’s attempt at a hefty American family tragedy à la Arthur Miller or August Wilson is going to be moved. The show certainly contains cultural observations that sound notes of truth on both the communal and domestic scale, and whatever identity you’re bringing to the room as a viewer, it’s possible for those echoes to stir you. The play itself, however, is a mess. Not that he necessarily needs my sympathy, but as The Other Americans wore on, I found myself feeling for Leguizamo. Taking a swing at the mode of playwriting that produced All My Sons is one thing — the Public’s artistic director Oskar Eustis praises Leguizamo in a program note for “making a bold and brave foray into an entirely new kind of writing.” But for that swing to be such a huge whiff, and then to be on stage playing your own protagonist while the excitement of the audience audibly wanes around you for two laborious hours … That’s rough, buddy.

Leguizamo, known on stage for the high-energy irreverence of shows like Freak, Ghetto Klown, and Latin History for Morons, is tackling that wounded mammoth, the American dream, through a Latin lens. Aspects of his own biography swirl through the play—like him, the patriarch of the family he’s created, Nelson Castro, is of Colombian descent, born and raised in Jackson Heights—and there’s the sense that Leguizamo is searching for a means of elucidating and humanizing, if not forgiving, the inflexible, self-defeating machismo of a community he knows and loves. Though The Other Americans is set (with no real narrative consequences) in 1998, it’s pretty clear how Nelson would have voted in 2016 (and probably, god help us, in 2024). The play is earnest and ambitious, clearly trying to strike a balance of humor and hurt, to invoke both sitcom patter and Pulitzer profundity while offering a specific vision of American brokenness — but despite his gift for character comedy, Leguizamo stumbles hard when it comes to writing dialogue. The figures that populate the Castros’ house in Forest Hills sound lumpen and ungainly, their small and big talk both loaded up with exposition, as if they’re dragging around sandbags. Everyone says exactly what they mean all the time, a single-frequency mode of communicating that verges on unactable.

Here’s Nelson’s son Nick (Trey Santiago-Hudson)—whose fraught return home after a long stay at a mental health clinic provides the play’s inciting incident—talking to his mother Patti (Luna Lauren Velez): “Ma, I need your help. In order to let go of what happened to me. I need to talk through with you what happened moment by moment when I was attacked.” Or here’s Nick’s sister Toni (Rebecca Jimenez) attempting a sibling bonding moment: “Crazy, Nick, y’know? You and me hanging out playing backgammon like we did back in Jackson Heights. It’s like nothing’s changed.” Jimenez especially puts her back into it, but this saying-what-I’m-doing language clunks no matter what. As for Nick, on the pretext of psychological catharsis, he does indeed recite a bunch of convenient narrative background. Leguizamo must sense on some level that he’s handed his character a lead weight, because eventually he has him pass it off: “I don’t remember the rest. Ma, please tell me the rest.”

She does, but not so much for Nick’s sake as ours. The circumstances that the play is straining to catch us up on are as follows: In his senior year of high school, Nick, the family’s golden boy, started dating a white girl named Leslie. Her ex and his friends attacked him with a baseball bat and tried to shove him in a washing machine at one of his dad’s laundromats. After recovering, Nick went to college (“I felt so ready and like I had moved on”) but then fell into a spiral. It’s implied that an attempt on his own life landed him in a treatment program for the better part of a year. Now he’s out and he wants to talk. His dad wants to do anything but.

That’s pretty much the play. Nelson is a Willy Loman, a failing wheeler-dealer and big talker with no game to back him up. (He keeps trying to borrow money for his “mats” from his successful half-sister Norma, played with tart professionalism and spiky heels by Rosa Evangelina Arredondo.) He’s also a Joe Keller, carrying a secret guilt that will eventually wreak its revenge. But there are no layers to the action, nothing to complicate the plodding from A to B to C. Nick tries to confront the past, Nelson avoids it, other characters fret around the edges, and this basic pattern repeats in slightly varied forms until the big father-son confrontation, which somehow manages to go by without sounding much more urgent than anything else. Leguizamo’s stage directions in the scene say things like “This hits Nelson like a ton of bricks,” “In total disbelief,” “pleading,” and “furious,” but neither he nor Santiago-Hudson really manages to connect with the intended weight of the circumstances or with his scene partner. Perhaps it was just the night I attended, but this floundering climax also contains one of the softest, saddest little stage slaps I’ve ever seen. Of course actors need to take care of each other, but the point is that nothing here lands.

Director Ruben Santiago-Hudson (also Nick’s real dad) seems to have thrown up his hands when it comes to knitting the play’s scenes together into a larger whole — at the end of each one, he douses the lights and turns up the music as fast as he can. No visual or symbolic vocabulary ever develops. It’s a double shame because Leguizamo actually has the seeds of a larger theatrical metaphor already sitting right there in The Other Americans. Or rather not sitting, but dancing. Every so often, Nelson cranks up the salsa music and busts a move, and Nick confesses that his real dream is to be a choreographer. Dancing, he tells his mother, is when “I’m the most me.” One of the best interactions in the play happens wordlessly, when Nelson and Nick engage in a dance off. Lorna Ventura’s choreography is playful and vigorous, and both Leguizamo and Santiago-Hudson can really move. This brief moment when they’re physically engaged is both their most intimate and their most tense — all the love, the unspoken desire for closeness and softness, and all the competition and struggle that Leguizamo wants to express come through, unburdened of speech.

“Nobody dances as an adult, honey,” Nelson scoffs when Nick tells his father his aspirations, but of course, we’ve seen the truth. The gulf between who Nelson really might be and how an aggregate of cultures—Colombian, American, capitalist, masculine—has molded him is the source of the play’s tragedy. We can see as much, but Leguizamo has not yet crafted something where we can deeply feel it.

The Other Americans is at the Public Theater through October 26.