Worrying new simulations show that a solar storm on par with the infamous Carrington Event could potentially wipe out every single satellite orbiting our planet, leaving us in a precarious and expensive predicament. And experts say such a powerful solar storm is inevitable and will hit our planet sooner or later.

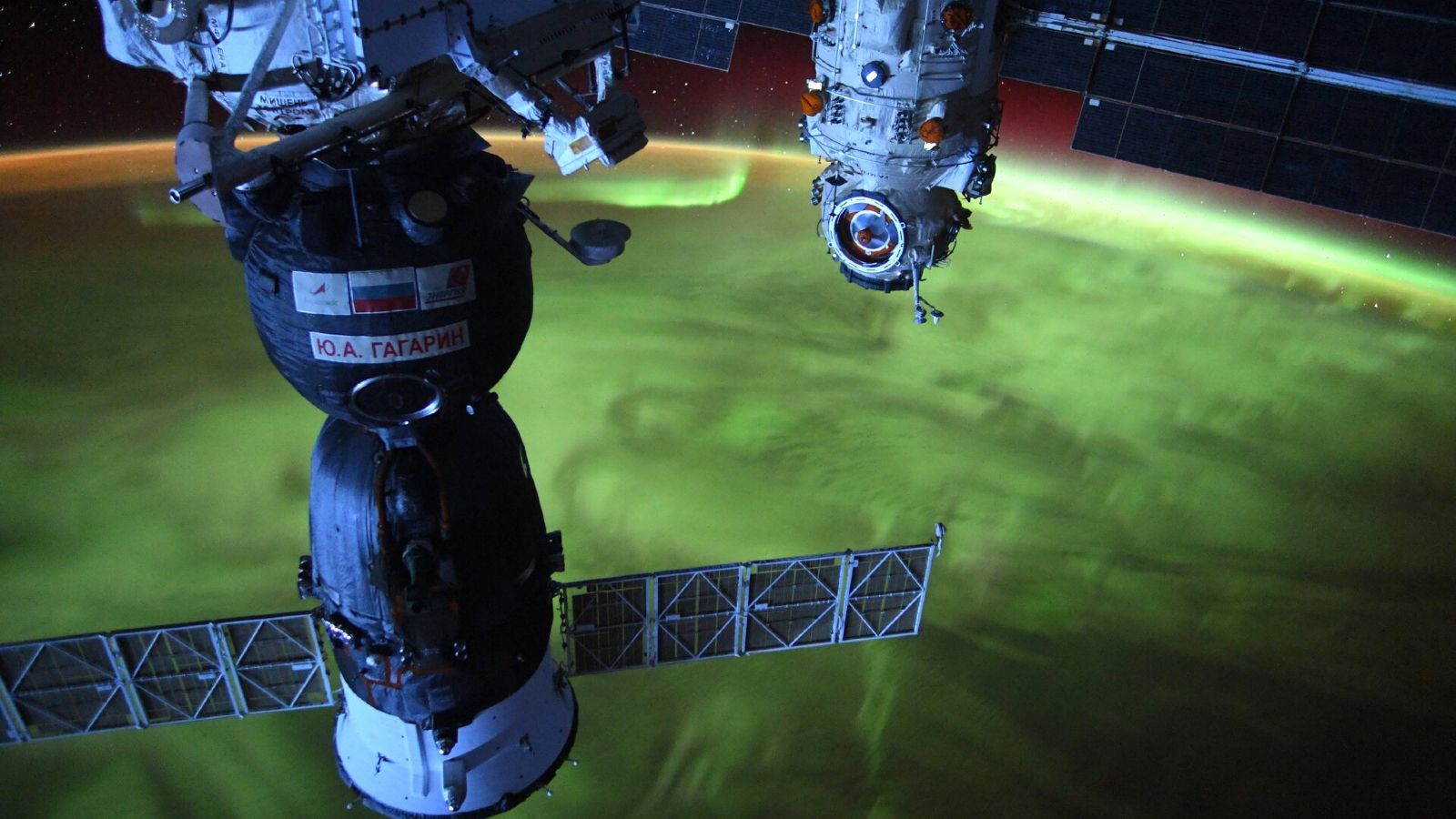

On Sept. 1, 1859, British astronomer Richard Carrington observed a brilliant flash of light coming from a gigantic sunspot that was about the same size as Jupiter. He had witnessed the most powerful solar flare in recorded history, and it was followed by a major disturbance to Earth’s magnetic field, known as a geomagnetic storm, which raged for almost a week and painted the skies with widespread auroras.

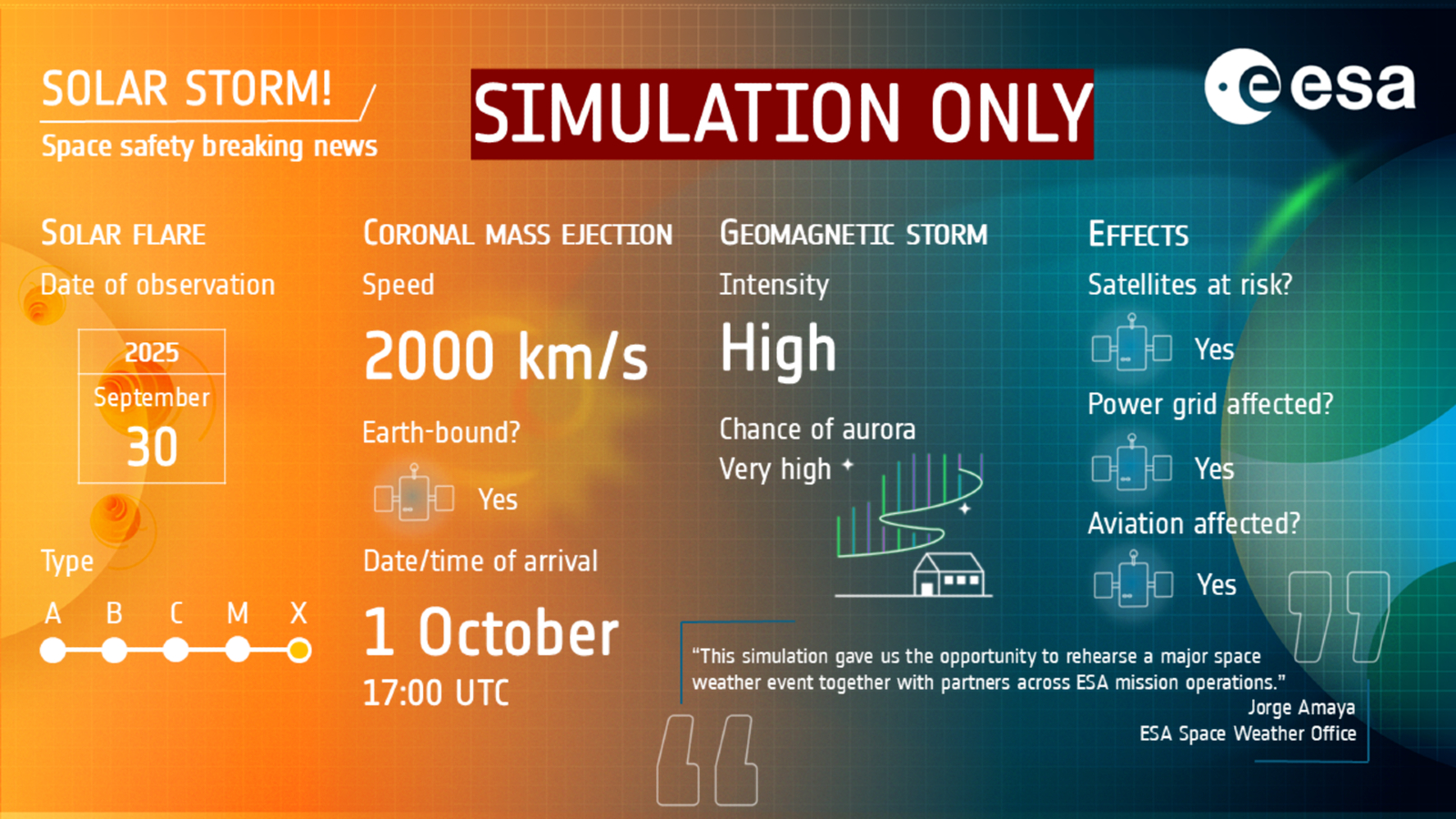

The simulations were part of a tabletop exercise carried out by researchers from multiple ESA departments at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany. The simulations were in preparation for the upcoming launch of ESA’s Sentinel-1D radio imaging satellite, which is currently scheduled for Nov. 4.

In the hypothetical scenario, an X45 magnitude solar flare — around five times more powerful than the most intense solar flare of the current solar cycle — suddenly erupts from the sun, showering Earth with a wave of intense radiation without warning. Around 15 hours later, after another wave of radiation, a gigantic cloud of fast-moving plasma known as a coronal mass ejection (CME), hits our planet at more than 4.4 million mph (7.1 million km/h), triggering a Carrington-like geomagnetic storm.

While the researchers’ response to this scenario was focused on how they would protect Sentinel-1D, the simulations also demonstrated how the global constellation of orbiting spacecraft would fare in such an event.

“The immense flow of energy ejected by the sun may cause damage to all our satellites in orbit,” Jorge Amaya, ESA’s space weather modeling coordinator , said in a statement. “Satellites in low-Earth orbit are typically better protected by our atmosphere and our magnetic field from space hazards, but an explosion of the magnitude of the Carrington Event would leave no spacecraft safe.”

In the exercise, there were three main threats that satellites faced. First, the initial wave of radiation from the solar flare, which could permanently or temporarily disable any satellites too far from Earth’s inner magnetic field. Second, a follow-up wave of radiation that scrambled navigation systems, increasing the likelihood of collisions. And third, the CME, which caused the upper atmosphere to swell outward as it soaked up the solar storm’s energy.

The atmospheric swelling is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of this triple threat, as it could increase satellites’ drag by up to 400%, pulling the spacecraft down to Earth, where they will either burn up in the atmosphere or crash to the planet’s surface.

We got a small taste of what the effects of such an event would be like during the record-breaking geomagnetic storm of May 2024, which was the most powerful of its kind for 21 years and triggered widespread aurora displays.

In addition to knocking a handful of satellites out of low Earth orbit, the 2024 storm significantly disrupted GPS systems, resulting in malfunctioning agricultural machinery that cost U.S. farmers around $500 million.

But that was only a drop in the ocean compared with the costs of a Carrington-like storm. A 2013 study analyzing the possible impact of such an event on North American power grids revealed that the U.S. could incur damages of up to $2.6 trillion, while the Planetary Society noted the true global cost is “beyond the scale of our comprehension.”

“When” not “if”

The reason that tabletop exercises like this are important is that another Carrington-like storm may not be far away.

“The key takeaway is that it’s not a question of if this will happen but when,” Gustavo Baldo Carvalho, a spacecraft operations expert who led the Sentinel-1D simulations, said in the statement.

Experts think that a Carrington-level storm occurs every 500 years on average, putting the odds of such an event occurring this century at around 12%.

While the latest exercise is further proof that we are not currently equipped to deal with this type of extreme scenario, researchers hope that by continually training for this eventuality we will become better able to deal with it.

“Simulating the impact of such [an] event is similar to predicting the effects of a pandemic,” Amaya said. “We will feel its real effect on our society only after the event, but we must be ready and have plans in place to react in a moment’s notice.”

But the longer we have to wait for the next megastorm, the more costly it will become, as the number of satellites orbiting our planet is predicted to rise by at least tenfold by 2050.