It’s very metal what they did: Stranger Things comes to Broadway.

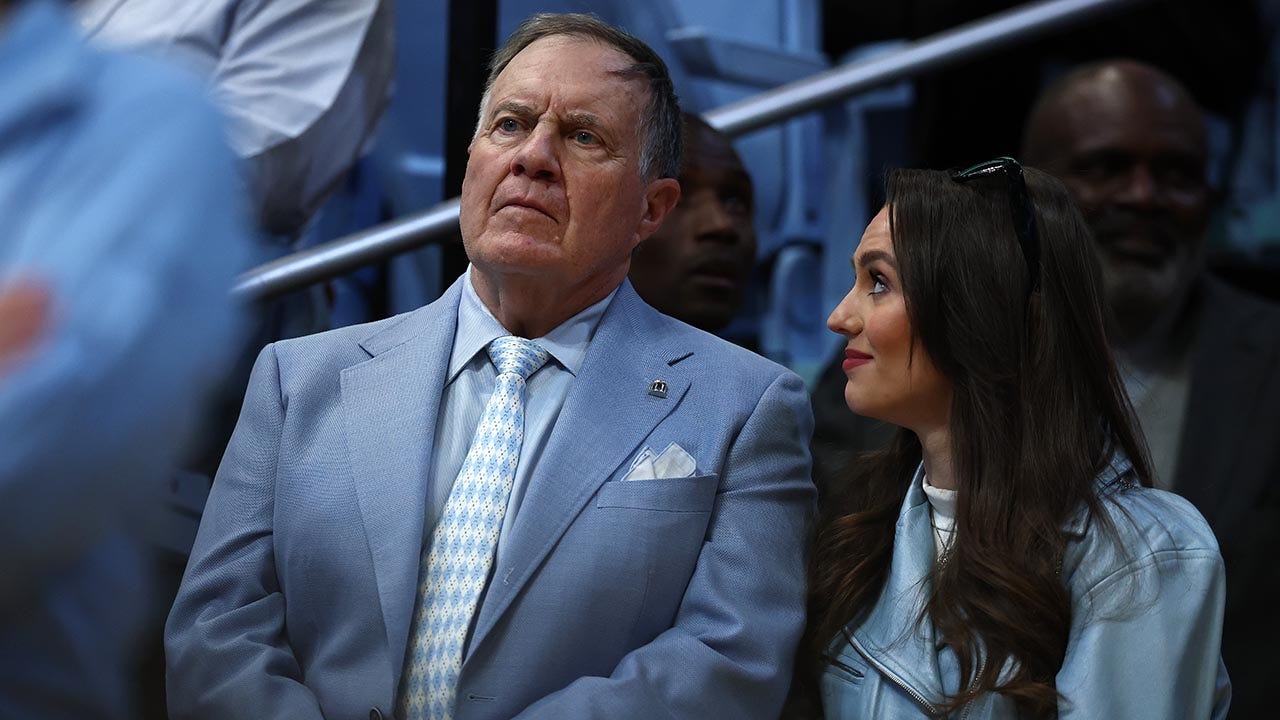

Photo: Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman

The London-born small-screen-to-big-stage techapalooza Stranger Things: The First Shadow couldn’t have landed at a more appropriate Broadway theater. On the third floor of the Marriott right off Times Square, the Marquis already feels like an entertainment-palace Experience™ — the kind of venue where a romantasy con, a ritzy corporate retreat, or a Jimmy Buffett brand extension would be equally at home. Bankrolled by Netflix and Sonia Friedman and unabashedly targeted at binge watchers, this Stranger Things (a prequel mostly set 20-odd years before season one of the Duffer brothers’ hit series) embraces the exit-through-the-gift-shop strategy with open tentacles. You can buy a cute plush Demogorgon in the lobby, along with, perhaps more disturbingly, a stuffed animal of Prancer, an orange cat that gets predictably and horribly mangled during the show.

The vibe, in other words, is lit. The crowd takes selfies with their souvenir monsters, and the cheer when the TV show’s moody title sequence fills up one of the set’s enormous screens and scrims as the story kicks off is — like much of the following almost three hours — deafening. If The First Shadow is purely an act of fan service, at least it’s an unapologetic and, if the audience around me was any judge, satisfying one. Is it a play? I mean, yes-ish? Is it an extravagant TV-meets-theater-meets-theme-park hybrid that probably has not entirely heartening implications for the future of Broadway? For sure. Is it also so unrelentingly absurd that it’s hard to be mad at? Absolutely.

Kate Trefry’s script — her first for the stage, based on a concept that she generated with the Duffers and Harry Potter vet Jack Thorne — seems to be based mostly on the premise that in order to sustain an audience somewhere as archaic as a theater, the thing inside the proscenium should attain maximum velocity and volume immediately and then stay there. I can only imagine the writing-room notes: Bigger, faster, louder! Another jump scare! Another flailing, electricity-sparking psychic break! Full speed ahead! Sound designer Paul Arditti racks up the sonic booms and spectral shrieks by the dozen. Jon Clark’s lights flash blindingly, then plunge into darkness, then send sinister tubes of red neon sliding across the set like old-school wipe transitions. The video and visual effects, by 59 Studio, are on pretty much constant blast (thankfully, they’re handled more effectively than many a recent Broadway show’s lazy deployment of LED screens). Perhaps out of a sense of frantic necessity, director Stephen Daldry has most of his cast performing at a similarly exaggerated scale.

The First Shadow takes place in the type of world where the two teenage misfits at the story’s center are the only real people. Braving the horrors of both the Upside Down and high school in Hawkins, Indiana, they navigate a universe of high-octane cutouts and cartoons. Playing young Joyce Maldonado, who turns out to be an extreme drama nerd, Alison Jaye hollers so much that I fear for her voice, which already sounds ragged beneath her character’s nonstop enthusiasm. When the shy, slump-shouldered new kid, Henry Creel (Louis McCartney, looking like the eerie love child of Peter Lorre and Pee-wee Herman) arrives in Hawkins, he receives the requisite tour of school cliques from senior-class president Sue Anderson (Ayana Cymone). Daldry (who co-directs with Justin Martin) lays the ham and cheese on thick as the inset turntables of Miriam Buether’s set spin and Sue introduces a literal merry-go-round of teen stock types: jocks, freaks, geeks. Young Jim Hopper (Burke Swanson) is there — cop’s son, bad boy, smarter than advertised — and so is baby Bob Newby (Juan Carlos), projecting intense Gene Belcher energy as the founder of the school’s AV club and self-appointed DJ of its radio station (very useful for regular exposition updates). Does Joyce’s fellow drama kid Alan (Eric Wiegand) hoist a skull aloft and declaim some Shakespeare in a bad English accent? Does it even need asking? If there’s an easy place to go in the big-box store of genre tropes, The First Shadow heads there with gusto, rampaging down the aisles and knocking full shelves of stuff into its shopping cart: Look, if the people want Fast Times at Hawkins High, give it to them. If there’s a way to shoehorn in a Las Vegas dance number, complete with jazz hands and ostrich feathers, do it! If you can start with a cold-open set ten years before the main action, with a gory, supernatural naval disaster and hints of a top-secret government project, why in god’s name wouldn’t you?

Although the show’s story at its most boiled-down follows poor, tormented Henry and his burgeoning relationship with fellow outcast Patty Newby (a sensitive, versatile Gabrielle Nevaeh) over the course of one calamitous year, its dramaturgy is really that of the fairground — or, perhaps more accurately, Instagram or TikTok. The attractions, diversions, and climaxes just keep on coming: cortisol, dopamine, cortisol, dopamine, boom-boom-boom. Henry, afflicted by a psychic link to the monsters behind the veil of the Stranger Things universe, has to go into writhing, spitting paroxysms at least once every 20 minutes or so. It must be exhausting, but McCartney and the audience are game: They both, it seems, signed up for a play with all the subtlety of a firehose.

What an audience largely made up of Netflix emigrants might not anticipate, and what I couldn’t stop giggling at, is the fact that The First Shadow’s plot is significantly bound up with a play-within-the-play. Joyce, with visionary zeal, puts her foot down at staging yet another production of Oklahoma! — instead, she’s going to direct a weird, risky musical called The Dark of the Moon, “the story of a Witchboy … who falls in love with a human woman and gives up his powers to be with her.” And because everybody in Hawkins apparently does everything together, from school to church to supposedly secret but very seriously produced drama-club productions, the whole gang’s onboard, with Henry as the Witchboy and Patty as his mortal love. I could have done with fewer gags surrounding Alan — who checks all the tedious boxes, from going Method to speaking in indecipherable Cockney to appearing in an outfit that screams Cats — but there’s still something sweet about a project like The First Shadow, with all its commercial bulk and all the digital streaming in its DNA, paying nerdy, affectionate homage to its newly adopted form. There’s even a nod (intentional or not) to Waiting for Guffman, as Joyce assures her cast that “Gary Lancaster from the Greater Indiana High School Theater Arts Scholarship will be here on opening night!” Notwithstanding all the Demogorgons, Mind Flayers, and portals to evil alternate dimensions you can shake an X-Ray Computed Tomograph at, the stakes for a teenage theater kid don’t get much higher than that.

_

Far away from Hawkins, in a cabin in Hurt, Virginia, at the sweaty height of summer, a different group of teenagers is battling through the days. They’re not solving mysteries or fighting transdimensional demons; instead, they’re dealing with the thing that probably makes us dream up a lot of that stuff in the first place — real, unfixable loss. After several months of delay during a strike by the stagehands’ union, the Atlantic Theater Company’s spring productions are back in swing: Eliya Smith’s Grief Camp is one of them, and if Smith’s shimmer-edged, soft-footed play shares anything with the Netflix behemoth uptown, it’s the heartening fact that both of them are driven by extremely talented young actors, many making their New York debuts. The show, under the gentle hand of Les Waters, also marks the Off Broadway premiere for Smith, who’s currently finishing an MFA at UT Austin — and while it doesn’t quite transcend the loose-limbed quality of a script in workshop mode, it also contains many moments of sharp poignancy and playful beauty.

Smith’s writing shines brightest in small units, be they sentences or scenes. The six teenagers at her imagined grief camp — a ramshackle labor of love run out of the home of its founder Rocky (voiced by Danny Wolohan), who remains unseen but asserts a deeply earnest, increasingly surreal presence over the camp loudspeaker — are all weird normies, ordinary weirdos. They are “not special,” Smith insists in a script note, but the collision of their normal teenagerdom with the various wrecking balls that have shattered each of their lives results in fragments of tilted humor, shards of half-poetry — a tentative, musical mix of the odd, the existential, and the mundane. “We should all totally do a Pina Bausch dance,” muses Esther (the wonderful Lark White) while lying on the cabin floor. “I love Pina Bausch!” says Bard (Arjun Athalye). “Who’s Pina Bausch?” says Luna (Grace Brennan, willowy and softly wacky). Earlier, in the middle of the night, Luna has crept out of her bunk bed and huddled in front of a box fan to do that thing every kid absolutely has to do if there’s a box fan around: “Brad,” she burbles into the whirring blades (poor Bard — everyone thinks his name is Brad). “Braaaaaad … I am sooooooooo … sweating through my pajamas … except for my feeeeet, which are … cold. I am making out with this fan. I love … cheese.”

Meanwhile, Blue — all big glasses, long hair, short bangs — shares pages from the script she’s writing for a solo musical about a woman who lives alone on an island in a mansion that’s somehow both purple and made of glass. “What’s it called?” asks Esther. “Untitled Mansion Island Purple House Project,” says Blue, who wants feedback but would “prefer if you kept it sort of granular.” Maaike Laanstra-Corn — whom I still recall as the highlight of a show I saw almost two years ago in a Brooklyn supermarket — brings the perfect blend of enthusiasm, innocence, and anxiety to the aspiring artist. For her, grief is sublimated in manic flights of imagination; for Gideon (Dominic Gross), it’s kept at bay by a stuffed dinosaur; and for Olivia (Renée-Nicole Powell), Esther’s brooding sister, it lashes out, snakelike, in brief, venomous spurts of sexuality. “Why can’t I have you?” she glowers at Cade (Jack DiFalco), a former camper turned counselor and a tense, thoughtful type in a jock’s body, who takes his duties to the campers seriously. His square-offs with Olivia, at once evasive and intrigued, escalate throughout the play, and like many of Smith’s scenes, they compel in the moment-to-moment — on what Blue might call the granular level.

It’s when one zooms out that Grief Camp begins to wobble. In her introduction to the script, Smith quotes Waters, who gave words to the effect she was hoping to create with the play’s chronology: “a sort of time soup.” That squares with the emotional experience of mourning, but it’s a tricky thing to achieve structural rigor and textural haze at the same time. Ultimately, Grief Camp leans into the latter at the former’s expense. Its devices for dealing with the passage of time — an obscure gong sound; the appearances of a guitarist (Alden Harris-McCoy) who seems more like a benign visitor from another dimension than what he is, an employee of the camp; hard cuts from night to day and back again — come off as a gestural mishmash, splashes of surreality for its own sake rather than reservoirs of meaning. (Similarly, Hurt, a real town in Virginia, is no more than a thematically appropriate name — no deeper sense of place develops.) Much floats; little accumulates. And while no play need proceed along traditional lines of rising action to climax to denouement and so on, Grief Camp still registers a bit too much like a collection of strong scene exercises, its connective tissue simply quirky when it should also be load-bearing. Its wavelets lap enticingly at our feet, but the breaker that might truly knock the breath out of us never comes.

Stranger Things: The First Shadow is at the Marquis Theatre.

Grief Camp is at Atlantic Theater Company through May 11.