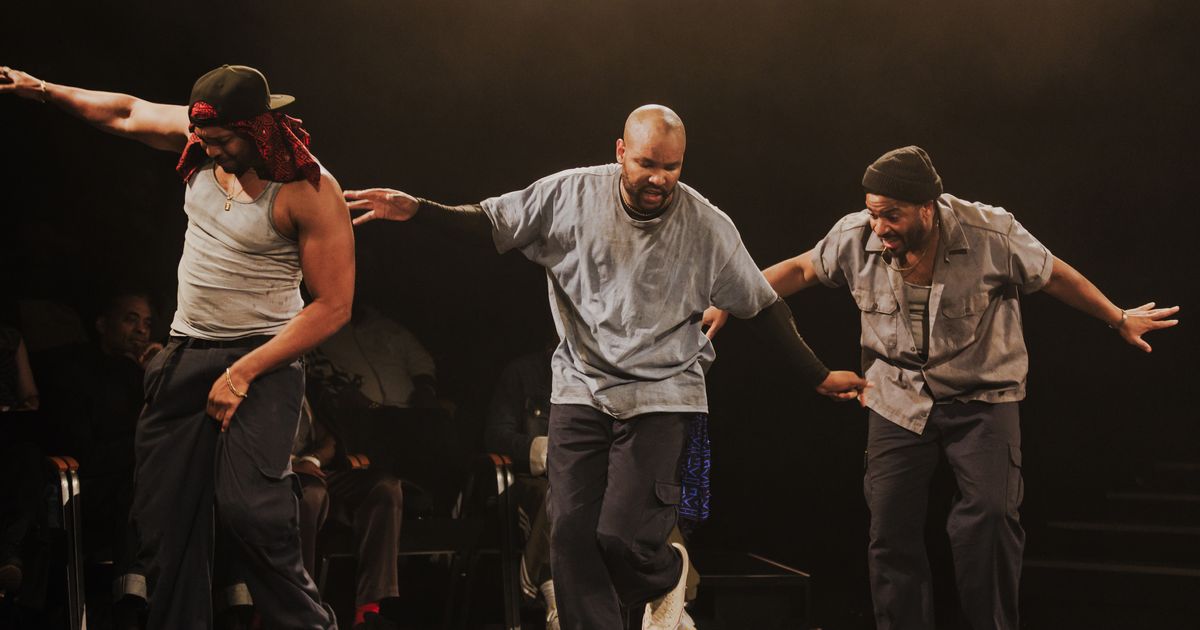

From The Brothers Size, at the Shed.

Photo: Marc J. Franklin

It’s high time The Brothers Size found its way back to New York. Tarell Alvin McCraney’s robust, balletic play has been making the rounds for almost 20 years, ever since its 2007 joint premiere at the Public Theater and London’s Young Vic. (Two years later, the Public presented the full trilogy of which the play is the first part, followed by In the Red and Brown Water and Marcus; Or the Secret of Sweet.) When he wrote the Brother/Sister Plays, McCraney was still a graduate student at the Yale School of Drama, where he would go on to chair the playwriting program in the institution’s more recent years as the David Geffen School of Drama. These days, he’s switched Geffens — in 2023, McCraney became artistic director of the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles, launching his tenure with a return to the dusty Louisiana crossroads of The Brothers Size, co-directing with Bijan Sheibani, who also staged the London premiere 18 years ago. It’s a version of this production — at once new and old, brought to life by collaborators with nearly as much history as the brothers of its title — that’s just arrived at the Shed, and the work onstage is a testament not only to the vigor of McCraney’s writing, but to the music and muscle, the sheer biorhythmic confidence, that can develop among artists who have the chance to hone their tools together over decades.

That sense of shared vocabulary and creative intimacy doesn’t just flow between the production’s co-directors. McCraney and André Holland — who’s riveting as the older of the brothers, Ogun Size — are also bringing a deep working relationship to bear. Back in 2009, in the Public’s take on the full triptych, a not-too-long-out-of-NYU Holland played the show’s mysterious third wheel, Elegba; now he provides the piece with its emotional anchor, shouldering the tragic weight that sits at the story’s center while Alani iLongwe’s bright, impulsive Oshoosi Size and Malcolm Mays’s subtle Elegba orbit him, shifting and “drifting,” as the play puts it, “like the moon.”

Ritual, cyclical movement hums in the cadences of McCraney’s at once rich and spare text. Phrases repeat like gestures in a dance; characters turn on a wheel of love, resentment, guilt, longing, and love again. Even on the page, it’s clear that The Brothers Size is a kind of incantation, perhaps even, ultimately, a kind of exorcism. Here, the three actors are accompanied by the musician Munir Zakee, whose percussive loops and accents provide a crucial fourth voice, harmonizing and fleshing out a score where every beat, every “Mmm” or “Huh!” or slap of a drum, has its place in the greater musical pulse. Sitting somewhere between myth and modernity (McCraney notes that the play takes place in “the distant present”), Size tells the story of its two brothers, the elder a mechanic and the younger perpetually “seeking employment” after a prison term. But the two men carry names that vault them into another sphere, calling into question, one could say, the brothers’ size. Ogun and Oshoosi are also the names of Yoruba deities, or Orishas. Elegba is, too, and as the play begins, Mays enters the near-empty space, arranged in the round by scenic designer Suzu Sakai, and walks in a wide circle, trailing a ring of white powder poured from a rusty old oil funnel behind him. It could be sand or moon dust, or even — as a late twist in the plot threatens — something more illicit. But what it is most of all is a kind of casting circle, a place for the songs of griots and the invocation of gods.

For Ogun and Oshoosi aren’t simply named after the ancient Orishas; the fact that even their unseen, ferociously Christian aunt, who raised them after the death of their mother, also bears a Yoruba name provides a glimpse of the wider ripples in McCraney’s play. In a certain light, his characters are the gods themselves, trapped by the confines of human bodies and of America’s long and ugly history of injustice. In the “distant present,” near the Louisiana Bayou, the royal warrior god of metalwork, Ogun, spends his days underneath broken-down cars. His brother, god of hunting and tracking, is caught in the cruel paradox of parole — somehow still unfree and searching for liberty and purpose, yearning for the seeming escape of his own car on the open road, always in danger of being hunted down himself. And the trickster god Elegba, Orisha of the crossroads, stands between them, a wily ex-con buddy of Oshoosi’s — not bad, not good, a Mephistophelean drifter who secretly longs for the fraternal intimacy that is his friend’s by birthright. (Though there are no weak links in the ensemble, I did long for more of a quicksilver glint from Mays, whose Elegba dims a bit in the fierce glow of the brothers.)

Sheibani and McCraney know that the way to bring out the sorcery of a play layered in myth and ritual is not to weigh it down. Their long-term collaboration has led to the confidence of intentional simplicity: Dede Ayite dresses all three men in variations of what could be prison attire — monochromatic cargo pants, T-shirts, and work shirts, their personalities only allowed to shine through the cracks. (In a clever touch, Mays’s Elegba wears the sole splash of color — red and black, the deity’s traditional hues — in a dirty bandana draped beneath his backwards ball cap.) No props are needed in Sakai’s conjuring circle of a stage, and Spencer Doughtie’s lights are given the space to sculpt striking tableaux out of the actors’ bodies in the void. The choreography by Juel D. Lane is fluid, precise, and often wonderfully giddy, especially in the warmer scenes between Holland and iLongwe. A sequence near the play’s end in which the brothers sing along, ever more rambunctiously, to Otis Redding’s recording of “Try a Little Tenderness” is at once utterly delightful in its unabashed miming and mugging and, bit by bit, as gutting as it gets.

In this same mode, McCraney often has his characters speak their own stage directions. “Kissing his teeth,” a Size will say with indignation before doing just that; “Ogun enters,” Holland intones before stepping into the circle; “Oshoosi smiles innocently,” declares iLongwe, getting a double rise out of his brother. Rather than creating Brechtian distance, the technique works a kind of alchemy between the play’s spoken and physicalized modes of poetry. It’s internal direction, keeping the actors’ bodies in constant motion, encouraging a dancelike engagement with the text while demanding, with its verbal dexterity, a certain amount of remove. As in Shakespeare, the actor as storyteller, as craftsperson, must be present at all times, fully awake and galloping alongside a character that’s fully embodied. That synchronicity — and the co-directors’ wise choice to lean into the play’s rich veins of humor — is what keeps The Brothers Size light on its toes, thrilling and energizing despite the fundamental heaviness of its heart. It’s the rare kind of production that lets a superb actor like Holland sparkle without highlighting him as a celebrity. He is a single point of a moving triangle, a single strand of a braid that McCraney has woven with one of theater’s intrinsic paradoxes infusing its fibers: It’s somehow both tight and spacious, a structure with its own integrity that still makes room for all the galvanizing possibilities of play.

The Brothers Size is at the Shed through September 28.