The bottom of the Japan Trench has some of the harshest conditions for life on Earth. But despite this, it is crawling with deep-sea creatures that dig intricate burrows and deep, corkscrew-like tunnels, new X-ray images show.

These creatures thrive 4.7 miles (7.5 kilometers) beneath the Pacific Ocean’s surface thanks to regular deliveries of sediment from above, according to a study published Tuesday (Feb. 18) in the journal Nature Communications. So-called turbidity currents — currents loaded with suspended particles — dump this sediment at the bottom of the trench, supplying oxygen and vital nutrients to the deepest reaches of the ocean.

Researchers have long thought that the ocean’s hadal zone, which extends between 3.7 and 6.8 miles (6 to 11 km) beneath the waves, is scarcely inhabited due to the harsh pressure, temperature and limited food availability. But these new findings provide evidence that an abundance of life does survive even in the deepest parts of the ocean.

“It is paradoxical that the deepest (hadal) parts of our oceans are more dynamic and support more diverse benthic [bottom-dwelling] communities than the surrounding abyssal plains,” study lead author Jussi Hovikoski and co-author Joonas Virtasalo, both researchers at the Geological Survey of Finland, told Live Science in an email.

Abyssal plains are flat expanses of muddy sediment found at depths of 1.9 to 3.7 miles (3 to 6 km) in the ocean’s abyssal zone — the layer above the hadal zone. Creatures on these plains have evolved to extract nutrients from the mud, and they often dig shallow burrows in search of their next meal, Hovikoski and Virtasalo said.

Related: Creepy ‘biotwang’ noises coming from the Mariana Trench finally explained after 10 years

But the hadal zone appears to host much more intense burrowing activity than abyssal plains, likely because huge amounts of sediment are siphoned to the bottom of ocean trenches, the researchers said.

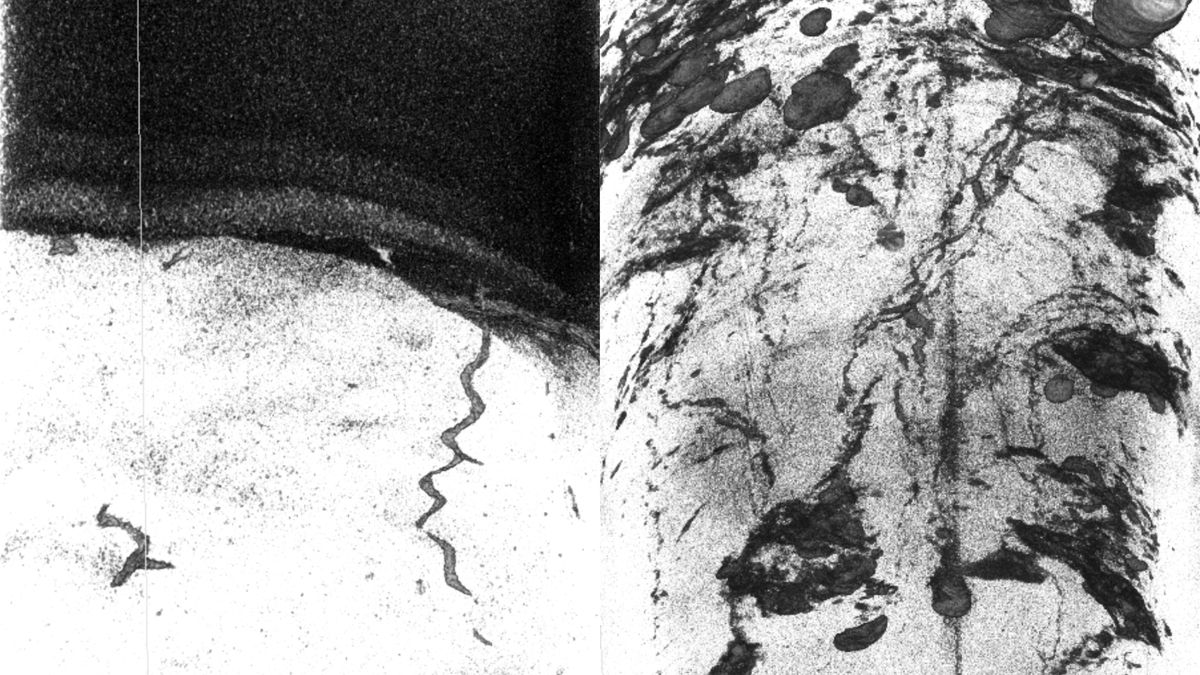

For the new study, scientists analyzed the top section of 20 sediment cores from the bottom of the Japan Trench, a 5-mile-deep (8 km) tectonic chasm located off the east coast of Japan along the Pacific Ring of Fire. The team used an X-ray scanner to obtain detailed cross-section images of the cores, revealing deep, extensive animal-burrow structures for the first time.

The X-ray scans revealed that some burrows in the Japan Trench are preserved thanks to deposits of minerals, such as pyrite, produced by microbes in the sediment. “Pyrite has higher density than sediment and such structures are exceptionally well visible in X-ray CT images,” Hovikoski and Virtasalo said.

Worm-like organisms and sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea) burrow into the sediment to feed — but it was beyond the scope of the study to identify the species responsible for the burrows.

Watch On

Sediment deliveries press reset

The researchers also performed geochemical analyses and examined the grain size of sediments in the cores. Their results showed that regular sediment deliveries from above are crucial for the survival and regeneration of animal and microbe communities at the bottom of the Japan Trench.

The effect of sediment falling to the bottom of the Japan Trench on bottom-dwelling creatures “can be compared to the effect of forest fires,” Hovikoski and Virtasalo said, because “fires reset vegetation successions and change key ecological parameters such as light, temperature and nutrient availability.” Similarly, clouds of sediment may initially suffocate creatures directly below, but once the dust settles, the nutrient-rich delivery resets environmental parameters and attracts animals from all around, the researchers said.

Opportunistic species flock to where sediment has landed as soon as the current ends to exploit the nutrients and oxygen inside the newly refreshed ocean floor, Hovikoski and Virtasalo said. The results of the study suggest sea cucumbers play a major role in these colonization events, the researchers said.

Over time, opportunists like sea cucumbers deplete the oxygen and nutrients in the fresh sediment. Microbes that thrive in oxygen-poor conditions take over, which in turn attracts invertebrates that feed on these microbes, the researchers said.

This cycle repeats itself every time a mass of sediment falls to the bottom of the trench, benefitting the entire deep-sea ecosystem by repeatedly delivering nutrients and oxygen, Hovikoski and Virtasalo said

“Owing to mass flows, the species composition and activity of benthic communities in trenches are also more diverse than those of the surrounding deep-sea floor,” the researchers said.