Physicists have created a new type of time crystal that may help confirm some fundamental theories about quantum interactions.

A standard time crystal is a new phase of matter that features perpetual motion without expending energy. According to Chong Zu, an assistant professor of physics at Washington University in St. Louis and one of the team’s lead researchers, a time crystal resembles a traditional crystal.

However, unlike a traditional crystal, which repeats a pattern across the physical dimension of space, a time crystal repeats a pattern of motion, rearranging its atoms in the same way over time, Zu said. This causes the time crystal to vibrate at a set frequency.

A time crystal is theoretically capable of cycling through the same pattern infinitely without requiring any additional power — like a watch that never needs to be wound. The reality, however, is that time crystals are incredibly fragile and thus succumb to environmental pressures fairly easily.

Although time crystals have been around since 2016, a team has achieved something unprecedented: They’ve created a novel type of time crystal called a time quasicrystal. A quasicrystal is a solid that, like a regular crystal, has atoms arranged in a specific, nonrandom way, but without a repeating pattern.

Related: Scientists create weird ‘time crystal’ from atoms inflated to be hundreds of times bigger than normal

This means that, unlike a standard time crystal that repeats the same pattern over and over, a time quasicrystal never repeats the way it arranges its atoms. Because there’s no repetition, the crystal vibrates at different frequencies. As the researchers state in their findings, published in the journal Physical Review X, time quasicrystals “are ordered but apparently not periodic.”

How to build a quasicrystal

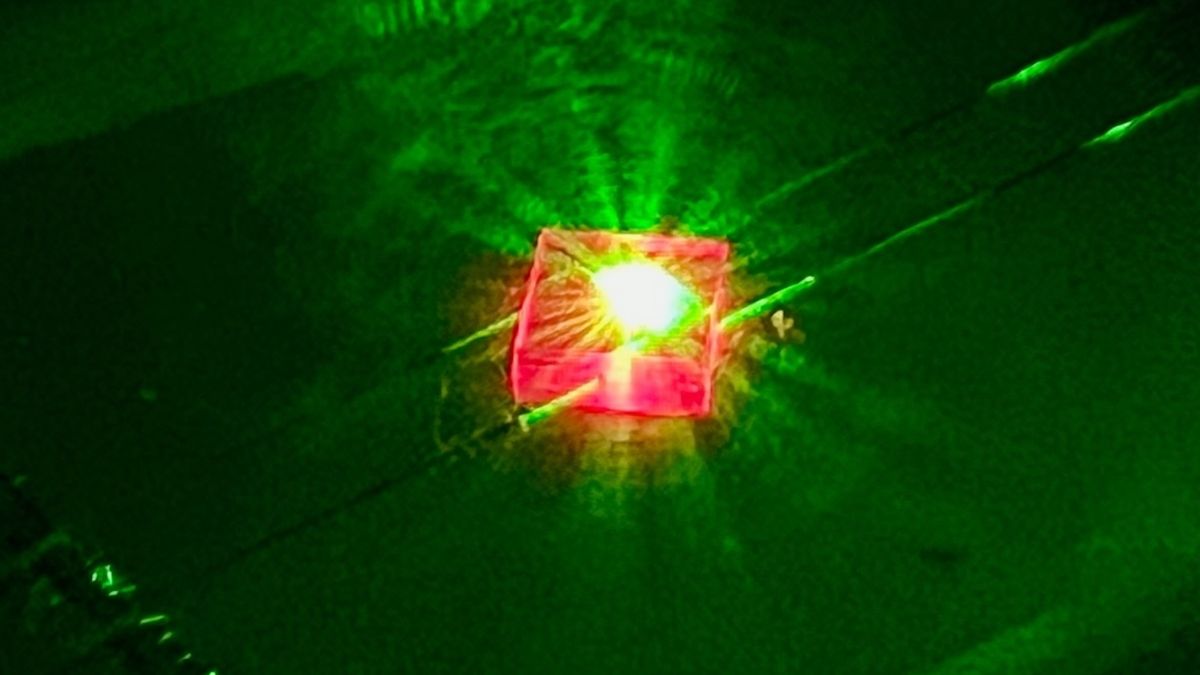

To create these new time quasicrystals, the researchers started with a millimeter-sized piece of diamond. Then, they created spaces inside the diamond’s structure by bombarding it with powerful beams of nitrogen. The nitrogen displaced carbon atoms within the diamond’s interior, leaving behind empty atomic chambers.

Nature abhors a vacuum, so electrons quickly flowed into these empty spaces and immediately began to interact with neighboring particles on a quantum level. Each time quasicrystal represents a network of more than a million of these empty spaces inside the diamond, though each measures just one micrometer (one-millionth of a meter).

“We used microwave pulses to start the rhythms in the time quasicrystals,” Bingtian Ye, a researcher at MIT and a co-author of the paper, said in a statement. “The microwaves help create order in time.”

Potential applications

One of the most important outcomes of the team’s research is that it confirms some basic theories of quantum mechanics, according to Zu. However, time quasicrystals may have practical applications in fields such as precision timekeeping, quantum computing, and quantum sensor technology.

For sensors, the crystal’s fragility and sensitivity are actually a boon; because they’re so sensitive to environmental factors like magnetism, they can be used to create extremely precise sensors.

For quantum computing, the material’s potential perpetual motion quality is the key.

“They could store quantum memory over long periods of time, essentially like a quantum analog of RAM,” Zu said. “We’re a long way from that sort of technology, but creating a time quasicrystal is a crucial first step.”