Nearly 35 years after its launch, the Hubble Space Telescope is still revealing new things about the cosmos.

In a newly released series of images, scientists used Hubble to probe a quasar 2.5 billion light-years away. The results deepen our understanding of how these mysterious objects develop — but also reveal “weird things” in the quasar’s vicinity that researchers cannot fully explain, the team wrote in a NASA statement.

“We’ve got a few blobs of different sizes, and a mysterious L-shaped filamentary structure,” Bin Ren, an astronomer at the Côte d’Azur Observatory and Côte d’Azur University in Nice, France, said in the statement. “This is all within 16,000 light-years of the black hole [at the quasar’s center].”

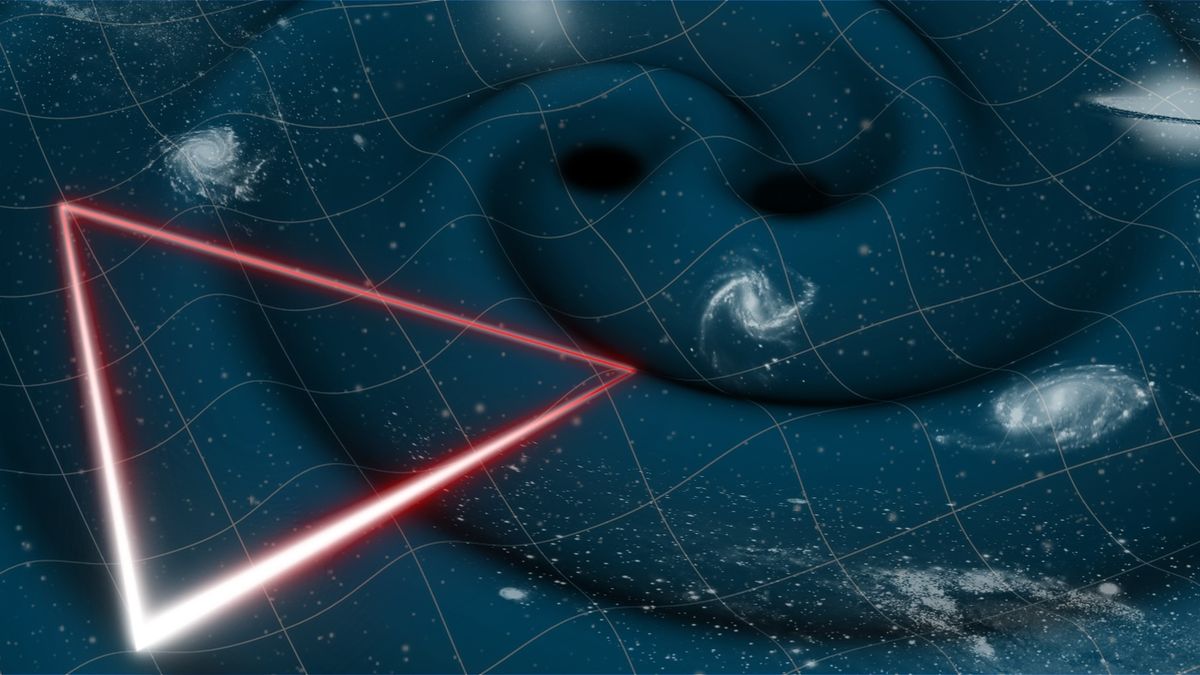

Quasar is short for “quasi-stellar radio source” — bright, star-like objects that emit radio waves and are powered by actively feeding supermassive black holes. The first quasars were identified in the 1950s, but many of their qualities remain mysterious. For example, due to their brightness, researchers don’t know much about the environments that typically surround quasars. However, Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) tool is able to block some of this excess light, similar to how the moon obscures the sun during a total solar eclipse.

Related: Black hole paradox that stumped Stephen Hawking may have a solution, new paper claims

Researchers pointed STIS at a known quasar named 3C 273. This particular celestial object was the first quasar to ever be officially recognized, in 1963, and is incredibly bright, emitting thousands of times more light than the average galaxy. Scientists theorize that this is because 3C 273 is surrounded by galactic debris and powered by a massive black hole devouring the remnants of the smaller galaxies in its vicinity.

Hubble’s instrument blocked enough light to examine the 300,000-light-year-long jet of material streaking out from 3C 273. Then, the researchers compared the images with Hubble data captured 22 years earlier. They found that the quasar’s jet has moved faster the farther away it gets from the location of the theorized black hole. This suggests that the black hole is helping drive the quasar’s brightness as it devours the remnants of smaller satellite galaxies. The “blobs” and L-shaped structures observed in the new images may be the remnants of those galaxies, the team added, but more study is needed to identify them conclusively.

“Hubble bridged a gap between the small-scale radio interferometry and large-scale optical imaging observations, and thus we can take an observational step towards a more complete understanding of quasar host morphology,” Ren said.

In coming years, scientists plan to use the James Webb Space Telescope to further deepen their understanding of this unique quasar by peering into its infrared spectrum.