The universe’s missing matter may have finally been found.

Astronomers think regular matter — that is, the stuff that isn’t dark matter — makes up about 15% of the universe’s total mass. However, for years, researchers have run into a problem when trying to quantify it: They haven’t been able to find about half of that “normal” matter in the stars, galaxies and other space structures we can see.

But now, a large, international team of researchers has found that the diffuse hydrogen gas surrounding most galaxies is significantly more extensive than scientists previously thought — so extensive, in fact, that it could account for most of the universe’s missing matter, the team says.

“The measurements are certainly consistent with finding all of the [missing] gas,” study co-author Simone Ferraro, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. The study is currently available on the preprint server arXiv and is undergoing peer review for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The hunt for the missing matter

For their investigation, the researchers used data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, as well as from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Chile.

Related: ‘The universe has thrown us a curveball’: Largest-ever map of space reveals we might have gotten dark energy totally wrong

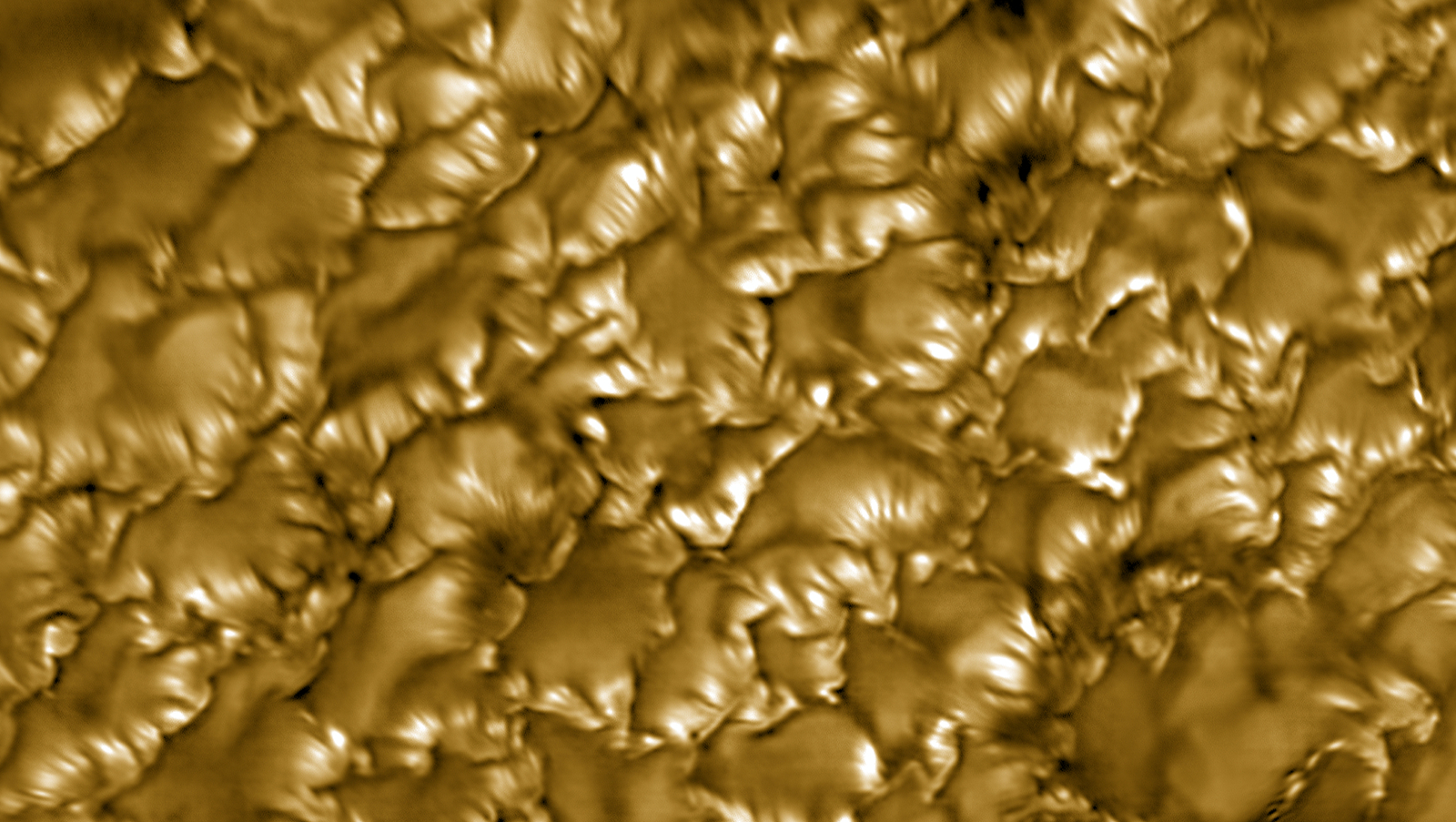

Using DESI observations, the team stacked images of approximately 7 million galaxies to measure the faint halos of ionized hydrogen gas at the galaxies’ edges. These halos are typically too faint to be seen by normal methods. So instead, the team measured how much the gas dimmed or brightened radiation from the cosmic microwave background — leftover radiation from the Big Bang that is prevalent throughout the universe.

The team also discovered that the clouds of ionized hydrogen formed ghostly, nearly invisible filaments between galaxies. If it connects most of the galaxies in the universe, this cosmic web would easily span far enough to account for the previously undetected matter.

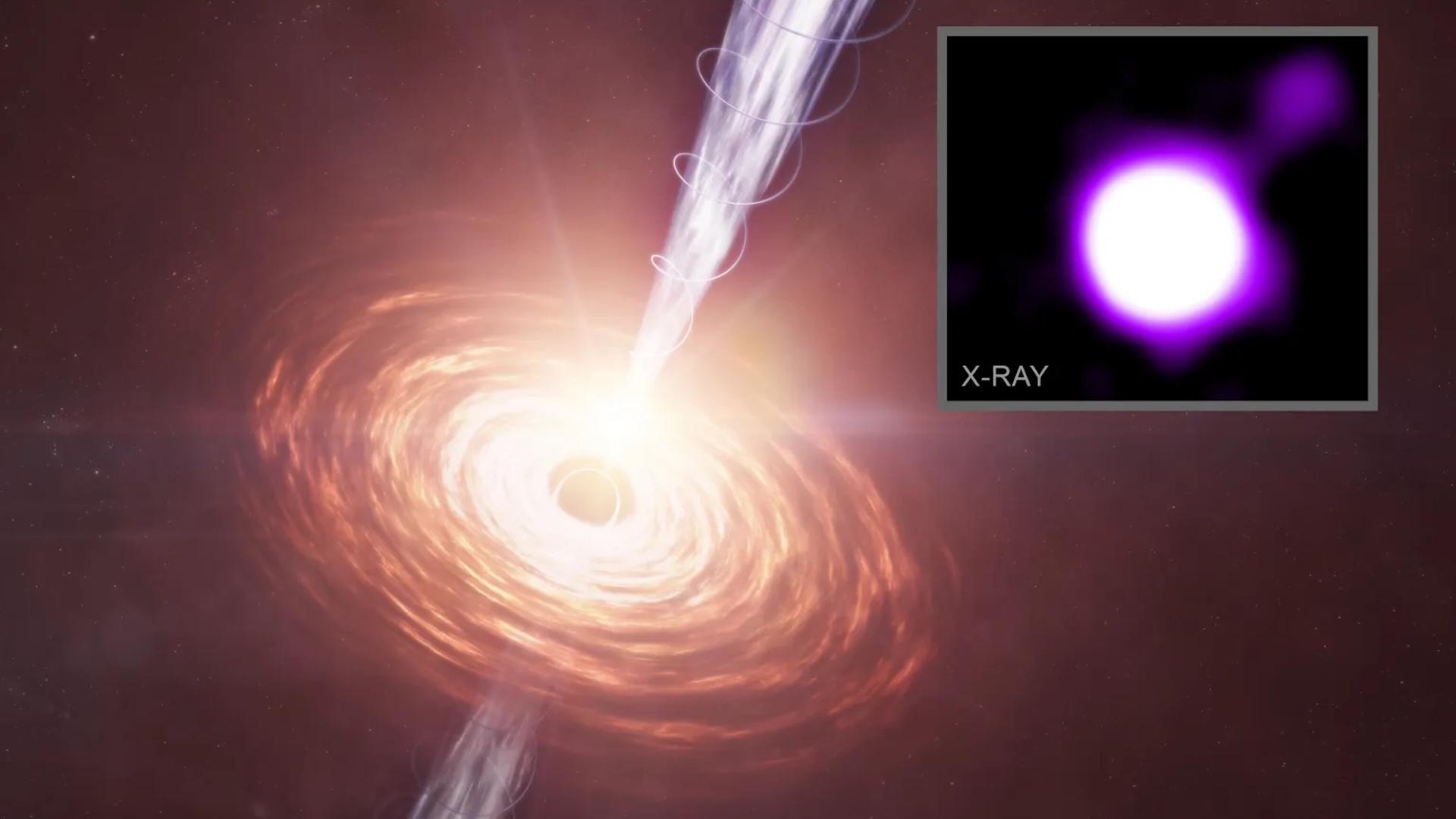

Black holes on duty

The discovery also may change what we know about black hole behavior. Scientists initially thought the supermassive black holes at the hearts of most galaxies only spewed jets of gas early in their life cycles. But the presence of such extensive diffuse gas clouds indicates that these black holes probably become active more frequently than previously thought.

“One of the hypotheses is that [black holes] turn on and off occasionally in what is called a duty cycle,” first study author Boryana Hadzhiyska, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley, said in the statement.

The next step will be to incorporate the new measurements into existing cosmological models. “There are a huge number of people interested in using our measurements to do a very thorough analysis that includes this gas,” Hadzhiyska said.