Mitochondria — the powerhouses of cells — carry unique DNA that is mutated in specific diseases, causing cells to be starved of energy. Now, scientists have uncovered a first-of-its-kind molecule that can reverse the effects of common mutations behind these genetic disorders.

“They [the mutations] can cause very different diseases for which no cure is available,” said Carlo Viscomi, an associate professor in the University of Padova’s Department of Biomedical Science and Padua Neuroscience Center in Italy.

“I think the paper really makes a breakthrough,” said Viscomi, who was not involved in the research but previously collaborated with some of the authors. “It may open amazing possibilities for these conditions.”

One limitation of the work is that it did not demonstrate how well the molecule works in a living animal or person, Viscomi said. But off the back of the research, scientists went on to develop a similar molecule that’s now being tested in a trial with humans. That trial is being run by Pretzel Therapeutics, which several authors of the paper are affiliated with as founders, consultants, employees or shareholders. The trial will test the safety of the drug in healthy individuals, and next year, the company plans to run a trial with people with mitochondrial diseases.

The team’s background research was “an important step” toward launching the ongoing trial, study co-author Claes Gustafsson, a professor in the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Cell Biology at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, told Live Science.

Related: Malfunctioning mitochondria may drive Crohn’s disease, early study hints

“Extremely variable” diseases

The study, published in April in the journal Nature, focused on polymerase gamma-related diseases, called POLG-related diseases for short. These rare, inherited conditions affect an estimated 1 in 10,000 people worldwide and are caused by mutations in the POLG gene, which codes for a key protein in mitochondria.

The DNA within mitochondria needs to be replicated as new mitochondria are made. Mitochondrial DNA must also be repaired after factors like oxidative stress damage it. However, around 300 different mutations in the POLG gene derail this replication-and-repair process by messing with the enzyme tasked with the job: polymerase gamma (POLG).

POLG mutants spur harmful mutations to accumulate in mitochondrial DNA, cause chunks of the DNA to be deleted over time, or both. POLG diseases result in a wide range of symptoms that vary among people and progress at different rates depending on which mutations a person carries and how many copies they’ve inherited from their parents. “It’s extremely variable,” Viscomi told Live Science.

Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome, one of the most severe POLG diseases, typically starts triggering symptoms between age 2 and 4; causes liver failure and seizures; and kills within four years of symptom onset. Some POLG-related diseases emerge earlier, shortly after birth, while others arise later, between the ages of 12 and 40, or even after 40. Those whose symptoms arise after 40 have the best prognosis and fairly mild symptoms at first, including droopy eyelids and eye-muscle weakness.

In general, people with POLG diseases survive between three months and 12 years after their symptoms first begin.

Because hundreds of mutations trigger these conditions, they would be challenging to address with gene-editing approaches, like CRISPR, said William Copeland, a senior investigator and head of the Mitochondrial DNA Replication Group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in the U.S., who was not involved in the study. For that reason, various groups have explored using small molecules to treat the diseases, with limited success, he told Live Science in an email.

What makes the new study unique is that it has introduced the “first drug specifically targeted against mutant forms of the POLG gene,” Copeland said. And at least in lab-dish experiments, the drug appears to “significantly” improve the function of the POLG protein, he added.

Related: We finally know why the brain uses so much energy

Hunt for a promising drug

The researchers theorized that if they could find a drug that enhanced the activity of healthy POLG, the same drug might work on mutant versions, too. They began by screening a diverse collection of 270,000 compounds to see how they impacted the activity of healthy POLG. This revealed one promising molecule that the team then chemically tweaked, to increase its potency, and tested on common mutants. They dubbed the optimized version of the molecule PZL-A.

In the study, the researchers focused on just four POLG mutants, rather than studying all 300. However, about 70% of people with POLG diseases carry at least one of these four mutations, they noted.

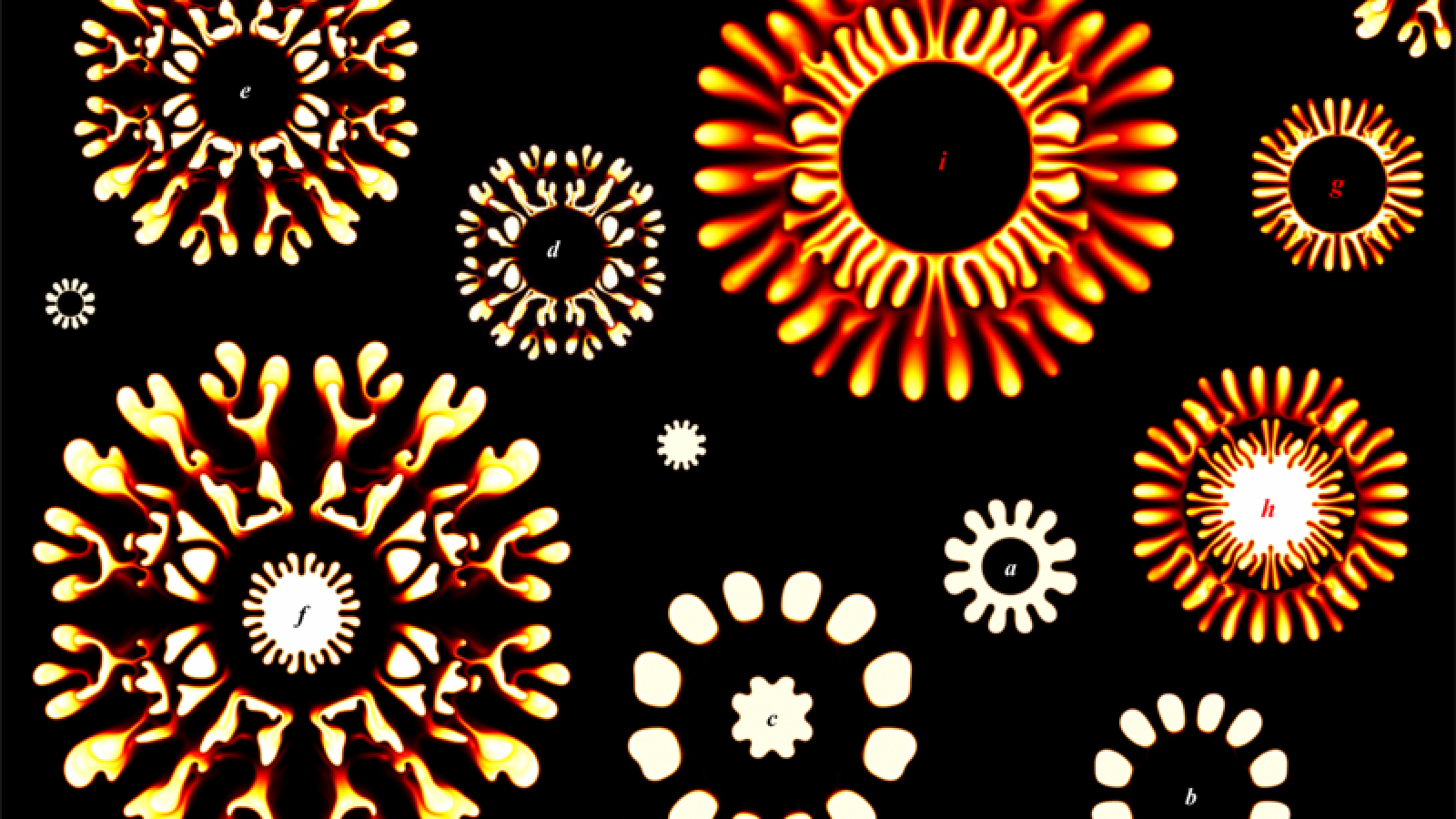

The team used a technique called cryogenic electron microscopy to reveal in fine detail how the molecule interacted with each mutant and with healthy POLG. The protein is composed of three parts that fit together: one “A” component and two “B” components. The analysis revealed that the PZL-A compound sits in a pocket between A and B. That pocket happens to be “unaffected by the most common disease-causing [POLG] mutations,” the authors noted in their paper.

By binding there, the molecule enhances the overall stability of the protein; this, in turn, boosts its ability to replicate and repair DNA, regardless of whether a mutation is present. “They didn’t test all the existing mutations, but the mutations they tested, they seem all to be ‘rescued,’ in a sense, by using this compound,” Viscomi said.

The researchers backed up these initial findings by running lab-dish experiments with cells from patients with the four common mutations they explored. First, the researchers depleted the mitochondrial DNA in the cells, to see how quickly the cells could recover that lost DNA. Cells treated with the compound recovered their DNA far faster than untreated cells did, and even kept up with the healthy version of the protein in some experiments.

“I wasn’t prepared for this outcome — that we would actually find one stone that will kill all these birds,” Gustafsson said. “But we did.”

Copeland agreed, saying, “I’m surprised that such a small molecule can stabilize the mutant forms of POLG,” as well as stabilize and alter the activity of healthy versions of the protein.

The team has begun testing the compound on additional POLG mutants. So far, they’ve found that “we see effects in many of these other mutations,” Gustafsson said. That recent work has yet to be published. Meanwhile, the clinical trial has just begun to test a molecule that is “structurally very much related” to PZL-A, he added.

The clinical trials will be needed to see if the newfound compound causes any unacceptable side effects and whether it has the expected effects in humans, Copeland said. If it does prove safe and effective, “I’m assuming the patient would have to be on continuous treatment for the duration of their life,” he added.

Such a treatment would fulfill an unmet need for people with these diseases, as current treatments are not aimed at curing the conditions but at managing patients’ symptoms.

In addition, Viscomi and Gustafsson both noted that the depletion of mitochondrial DNA is tied to diseases of aging, including neurodegenerative conditions. So it may be that, beyond POLG diseases, scientists could explore additional applications for the compound.