Scientists have discovered a new type of cell in the liver that plays a critical role in repairing damage.

These “leader cells” are responsible for dragging healthy tissue into wounds as they heal after injury, essentially filling the gap and allowing cellular regeneration to occur.

This newfound knowledge could be used to create novel treatments for liver disease, researchers say. They described their findings in a paper published May 1 in the journal Nature.

“Cutting-edge technologies have allowed us to study human liver regeneration in high definition for the first time, facilitating the identification of a cell type that is critical for liver repair,” Dr. Neil Henderson, co-senior study author and a professor at the Centre for Inflammation Research at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, said in a statement. “We hope that our findings will accelerate the discovery of much-needed new treatments for patients with liver disease.”

Related: Dozens of unexplained cases of liver disease seen in UK children

The liver helps remove toxins from our blood, produces bile to remove waste products of digestion and metabolizes drugs. The liver also has the remarkable ability to repair itself after damage, for instance due to viral infections such as hepatitis, drug-induced injury and alcoholic liver disease.

However, sometimes the liver is so damaged that it can’t heal quickly enough, leading to acute liver failure, which affects more than 2,000 Americans a year. The condition can happen within 48 hours, potentially causing symptoms such as yellowing of the skin, excessive bleeding, brain swelling and multi-organ dysfunction.

Depending on the cause, some cases of acute liver failure, for example those induced by poisoning, can be reversed with drugs. However, in severe cases, the only cure is an emergency liver transplant. There is, therefore, an urgent need for new therapies that enhance the liver’s own natural ability to heal itself, say the authors of the new paper.

To better characterize this healing process, Henderson and colleagues studied liver tissue from patients with acute liver failure who’d gone on to receive transplants. Although many liver cells from these patients could multiply, their livers still showed signs of significant damage. The team therefore wondered whether repairing the liver required more than simply making new cells to replace the damaged ones.

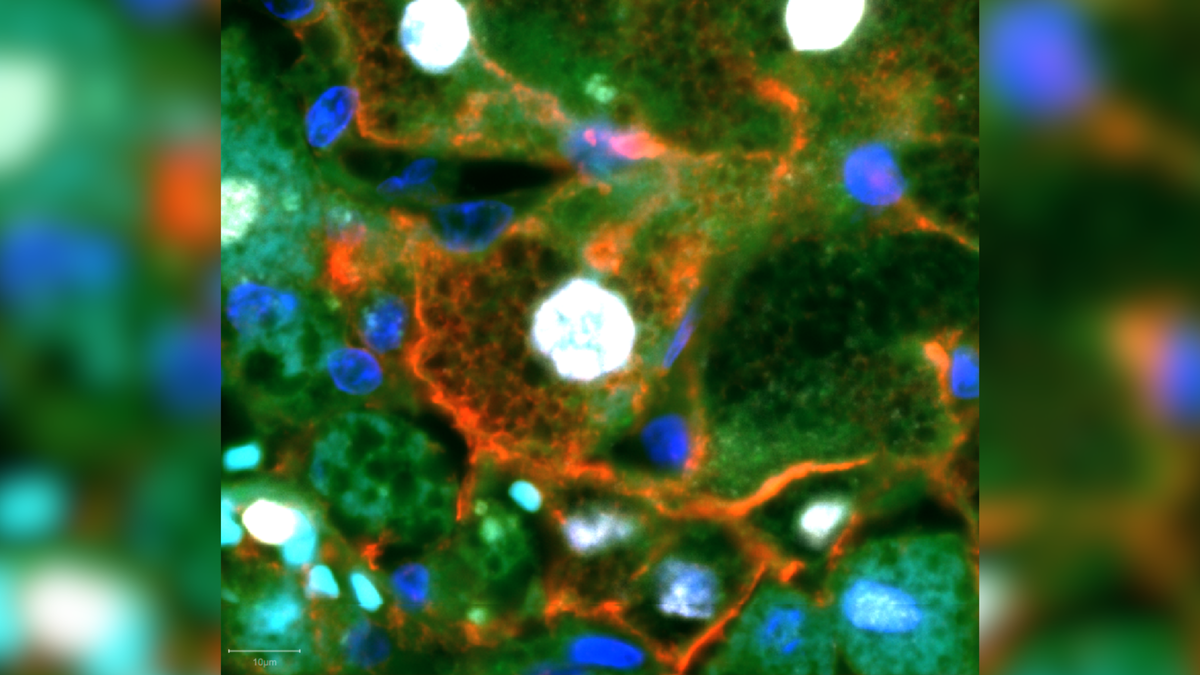

So the team sequenced the genes of every liver cell, comparing those from patients with acute liver failure to ones from healthy individuals. This allowed them to generate an “atlas” of liver regeneration, showcasing which cells were active and when during the repair process, including the freshly-found leader cells.

The team also viewed these cells in mice as they helped repair the liver after acetaminophen-induced injury. They noticed that during wound healing, leader cells emerge first, to rapidly close the wound, before cell proliferation helps further seal the gap. This suggests that the liver prioritizes wound closure before new tissue is made to prevent bacteria entering the organ from the gut and causing widespread infection, the authors wrote in the paper.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line “Health Desk Q,” and you may see your question answered on the website!