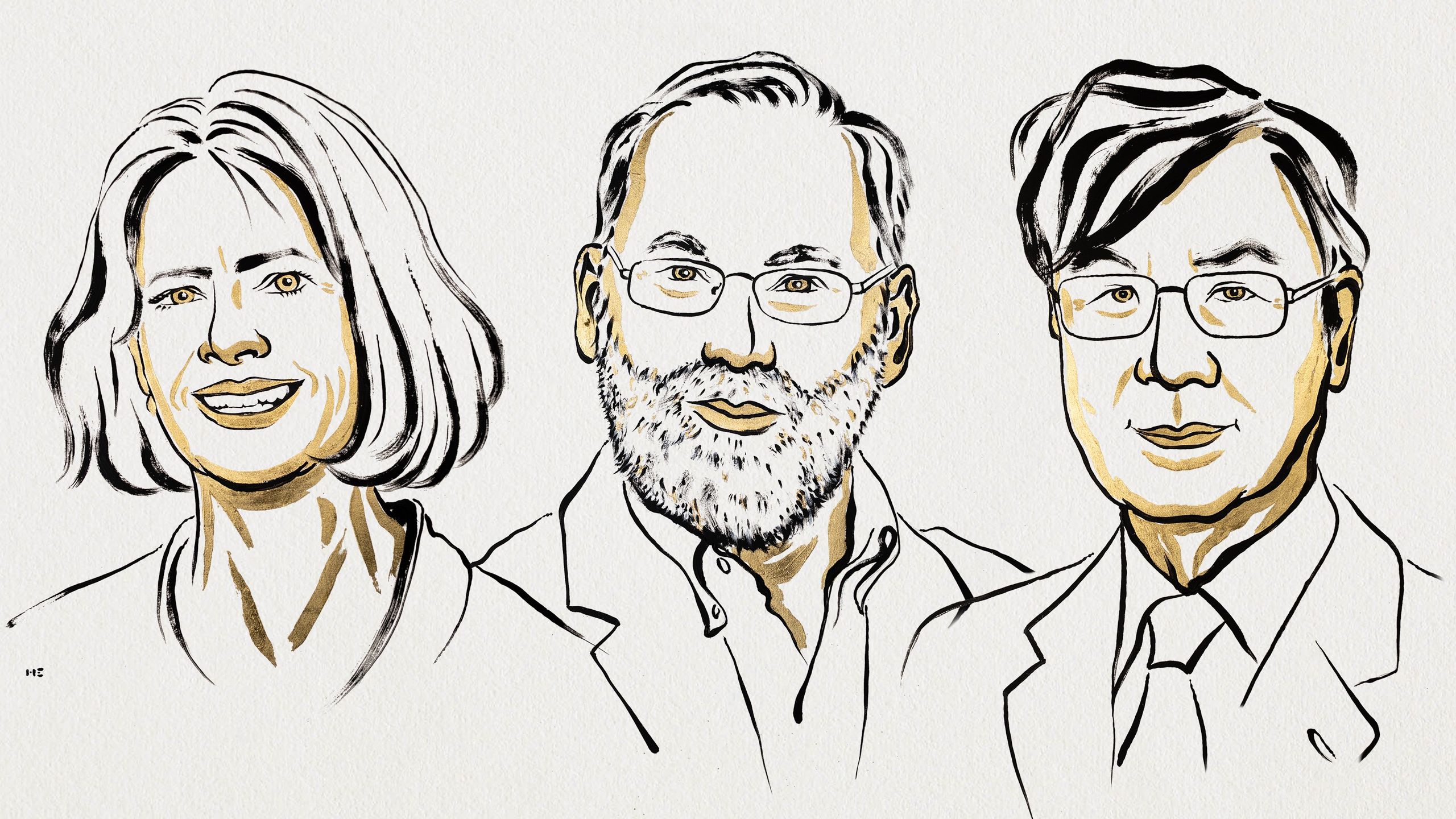

A trio of researchers has won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering how the immune system is prevented from attacking our own bodies.

Mary E. Brunkow of the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, Fred Ramsdell of Sonoma Biotherapeutics in San Francisco, and Shimon Sakaguchi of Osaka University in Japan were awarded the prize “for their discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance.” The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet announced the winners at a ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden, on Monday (Oct. 6).

“Their discoveries have been decisive for our understanding of how the immune system functions and why we do not all develop serious autoimmune diseases,” Olle Kämpe, chair of the Nobel Committee, said in a statement.

Our immune system has to protect the body from a variety of harmful microbes, acting like a biological bodyguard. Some sneaky invaders, such as viruses, can mimic human cells, so part of the immune system’s job is to determine who is on the guest list, while kicking out anything that shouldn’t be there.

The new Nobel Prize winners revealed how our bodies use regulatory T cells to keep the immune system in check. Their work has launched a new field in peripheral tolerance research and led to the development of new medical treatments, including for cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Sakaguchi made the first key peripheral immune tolerance discovery in 1995, when many researchers thought that the immune system only developed tolerance through a process called central tolerance, during which harmful immune cells are dealt with in the thymus — a specialized organ in the chest that makes white blood cells.

However, Sakaguchi demonstrated that the immune system has additional complexities by discovering immune cells, called regulatory T cells, that suppress overactive immune responses to protect the body’s cells from autoimmune diseases.

These specialist cells keep an eye on other immune cells to ensure the immune system tolerates the body’s natural tissues. In other words, they prevent our biological bodyguard from getting overzealous.

Brunkow and Ramsdell’s contribution came six years later with their discovery that some mice had a gene mutation, named Foxp3, that makes them especially vulnerable to autoimmune diseases. The pair also found that alterations to the human version of this gene were responsible for immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, an autoimmune disease.

In 2003, Sakaguchi demonstrated that the Foxp3 gene is responsible for governing the development of regulatory T cells.

Stay tuned for more Nobel Prize announcements this week. The next announcement will be on Tuesday (Oct. 7), when we’ll learn who is awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize for Physics.