Adrienne Warren and Nick Jonas in The Last Five Years.

Photo: Matthew Murphy

The “I’ve been an asshole, but I know I’ve been an asshole, but I’m still going to capitalize on the fact that I’ve been an asshole” piece of art is a specific vibe, and 2001 was a peak year for it. That moment gave us Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years, a kind of stripped-down twist on Merrily We Roll Along for the Gen X–millennial cusp and still a beloved standard for NETC hopefuls and college-theater departments from here to Skokie (where the show premiered). In 1999, at 29 years old, Brown had already won a Tony for Parade; meanwhile, his marriage to actor Theresa O’Neill had fallen apart. Two years later came this wistful, restless two-hander about the breakdown of a marriage between a young Jewish writer whose star is rapidly rising and his partner, an actress who can’t escape summer stock. Art didn’t exactly soothe the wounds of life: O’Neill sued Brown and Brown sued her back. Lincoln Center stepped away from producing the musical’s New York premiere in 2002, possibly because of the lawsuits, and Brown—despite insisting that the show wasn’t autobiographical—rewrote its second number to make the female protagonist less like O’Neill.

Well, it’s all water under The Bridges of Madison County by this point. But for anyone staging The Last Five Years, questions still hover around how to balance and complicate the musical’s sympathies. For Cathy, the actress, the story runs backward, from heartbreak to first magical meeting. For Jamie, the author, events go forward — he begins as an aspiring, about-to-get-his-break novelist who’s thrilled to belt out an ode to his “Shiksa Goddess” (“I’ve had Shabbas dinners on Friday nights / With every Shapiro in Washington Heights,” he sings giddily. “But the minute I first met you / I could barely catch my breath”). He ends—not unlike another successful artist who’s recently stared disconsolately out from a Broadway stage—famous and fortunate, and also a cheater who’s slipping off his wedding ring, leaving a note, and walking away.

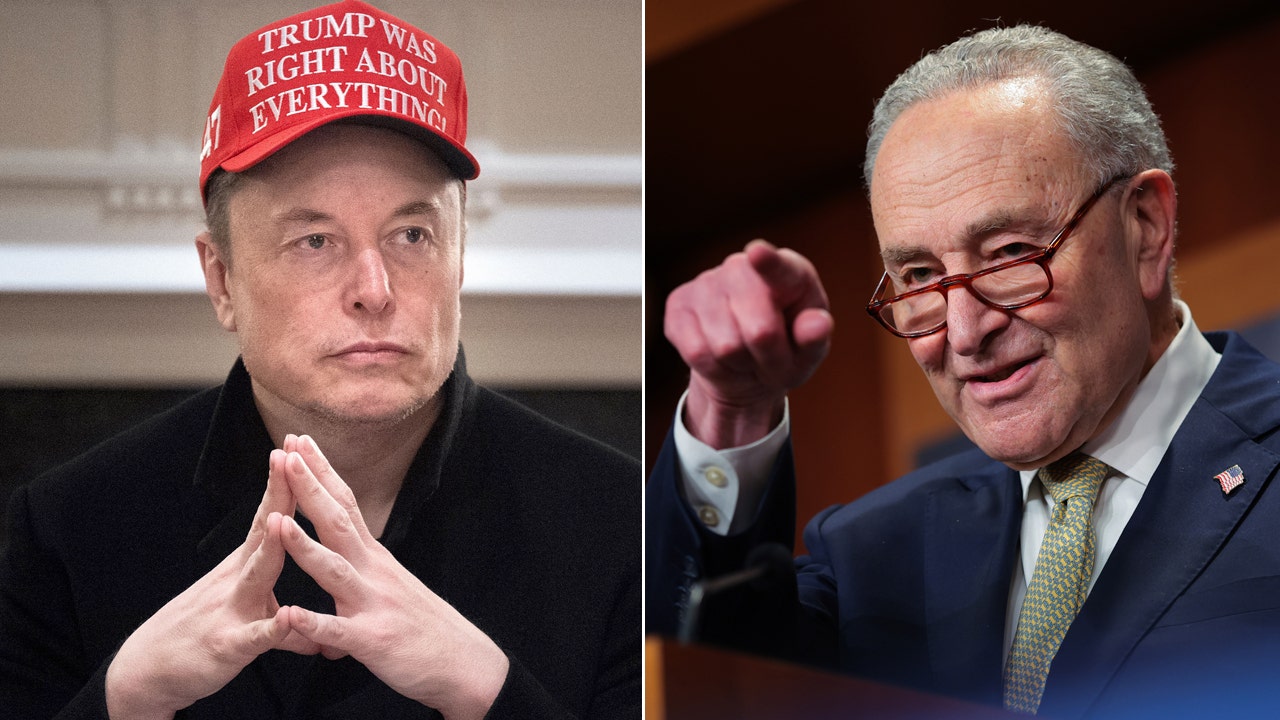

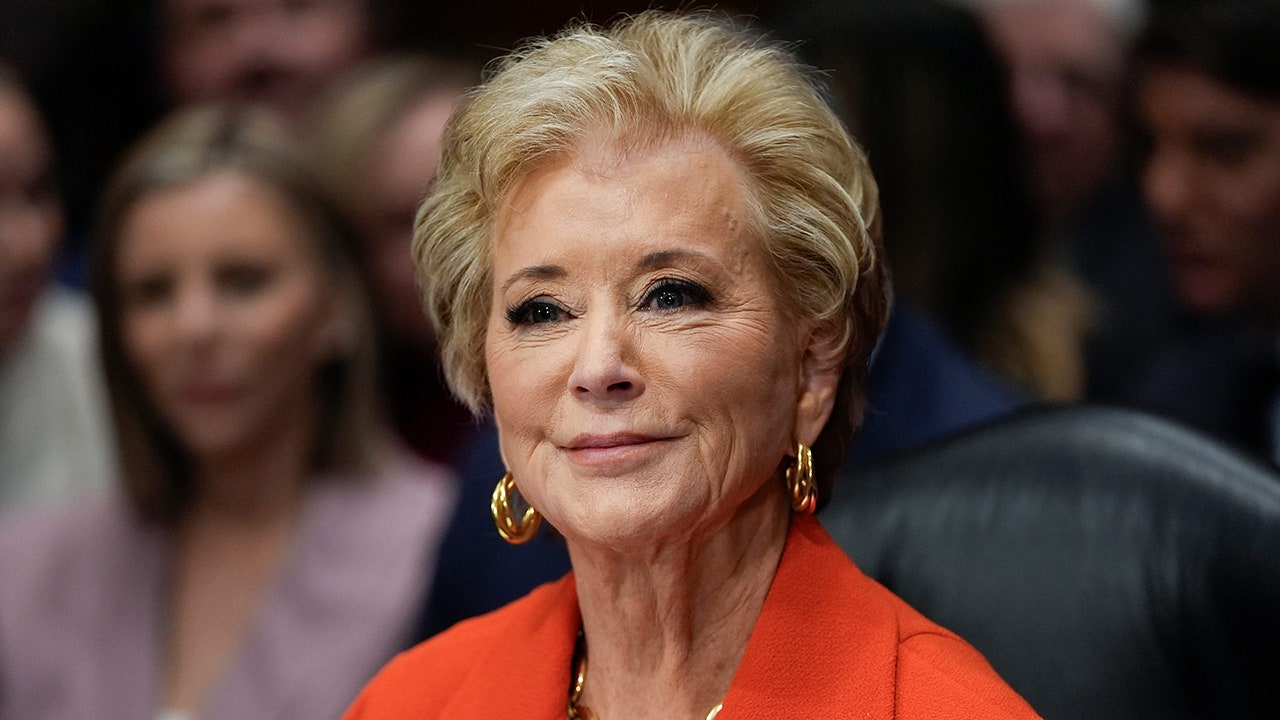

Whitney White’s revival is sleek and unpretentious—Stacey Derosier’s lights, elegantly juxtaposing oranges, golds, and blues, are particularly lovely in helping to score the story’s temporal and spiritual separations—but it hasn’t quite solved the asshole problem. Emotionally, this Last Five Years goes the route it’s easiest for the show to go: It belongs unquestionably to its Cathy, the luminous Adrienne Warren. It would be tough to accept a performer so radiant, with such a killer voice, as an actor who can’t get the gig — except that Warren brings such sincere frustration and longing to Cathy’s struggles that she becomes an unhappy reminder of just how many extraordinary talents there are out there, battling it out against a system that refuses to give. As we follow her through a series of soul-crushing auditions in “Climbing Uphill,” the satirical accuracy gets almost almost too agonizing. “Why is the director staring at his crotch?” she sings frantically, her internal monologue emerging as she executes a series of discount-Fosse dance moves:

Why is that man staring at my résumé?

Don’t stare at my résumé.

I made up half my résumé.

Look at me…

No, not at my shoes.

Don’t look at my shoes —

I hate these fucking shoes.

Why did I pick these shoes?

Why did I pick this song?

Why did I pick this career? …

Why am I working so hard?

These are the people who cast NeNe Leakes in a musical.

NeNe Leakes, in earlier productions, was Linda Blair: The show has received a few tweaks for the new era of celebrity stunt casting. Whether its creative team feels any sense of irony about its own participation in that trend—his name is Nick Jonas and he’s playing Jamie—can’t be seen onstage. There, Jonas does his best, but his Jamie just doesn’t have enough going on for us to withdraw half our hearts from Warren’s Cathy and invest them in him. As a singer, he’s predictably stronger in the poppier, swoopier segments; despite being mic’d up, he gets breathy and hard to hear in his lower range. But it’s not his voice that lets him down; it’s the lack of contours in his character. This Jamie is too easily dismissed as Basically Selfish Straight White Guy 101. He (Jamie, not, notably, Jonas) may be emphatically Jewish—the brothers Rick and Jeff Kuperman’s choreography includes its share of Fiddler–esque dance moves, and at one point Jamie prefaces giving a Christmas gift to Cathy with a big song-and-dance of a fable about a tailor named Schmuel—but the primary drivers of his personality, and of the growing strife in his marriage, come off as basic hetero stereotypes. He’s ambitious; she’s needy. He cheats; she suffers. He can’t stop staring at every “pair of breasts” that walks by after they’re married; she sings about “forever” and wanting to bear his child. “I don’t want you to hurt,” he sings to her four years along in his story arc. “But … No one can give you courage / No one can thicken your skin / I will not fail so you can be comfortable, Cathy. / I will not lose because you can’t win.”

Those are some devastating lyrics, with the potential, to Brown’s credit, to land not just with blunt force but with the sting of truth. Being the one in a relationship to feel like your horse is galloping far ahead of your partner’s can bring its own kind of anxiety and empathic pain. But White and Jonas haven’t built an anxious or a particularly compassionate Jamie. Even in the character’s early song of snowballing success, Jonas plays the whole thing psyched up and triumphant, giving no nuance to the upbeat number’s giveaway refrain, “I’ve got a singular impression / Things are moving too fast.” Later, “The Schmuel Song” feels less like an offering to Cathy and more like a look-at-me performance she’s got to sit through. When Jamie at last confronts her with the possibility of her own timidity and self-sabotage, he seems only personally aggrieved, not racked by the complexities of their power dynamic, not fighting for her despite, or even through, the harshness of what he’s got to say.

“There’s no message to the show,” Brown told Playbill in 2022. “I don’t have a statement to make. It’s just a story about two people who want desperately to be together and can’t be … It’s just a tiny bird that flies beautifully.” That’s fine, but for that flight to achieve real beauty, a production has to find a way to correct for the lopsidedness that’s baked into the script. Here, Warren’s performance is the only thing to truly soar. “I can do better than that,” she sings to Jamie, recounting her past in her own early-in-the-relationship song of hope and chutzpah. If only it weren’t so easy to wish she were singing it in his wake.

The Last Five Years is at the Hudson Theatre.