Scientists have uncovered new insights into the diet of the infamous Tsavo man-eating lions after analyzing clumps of hair found in the predators’ teeth.

In 1898, a pair of male lions (Panthera leo) killed and devoured dozens of workers constructing a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya — killing at least 35 people. They stalked and terrorized the workers for nine months before being shot later that year. Since then, their bodies have been kept at the Field museum of Natural History in Chicago.

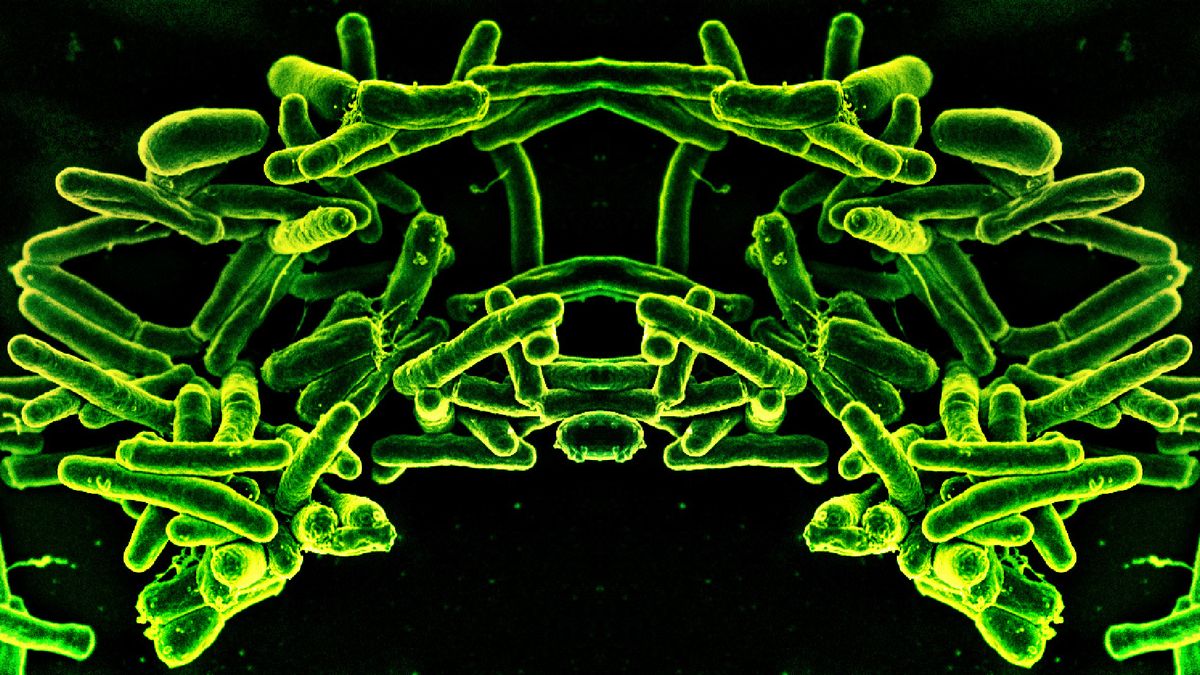

In a new study, scientists extracted the DNA from clumps of hair found in the lions’ teeth.

Their findings identified six prey species, which raises new questions about the lions’ distribution in Kenya at the time they were alive.

“We found mitochondrial genetic material from giraffe, human, oryx, waterbuck, wildebeest and zebra as prey, and also identified hair that came from the lions themselves,” study co-author Alida de Flamingh, a biologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, told Live Science in an email. The researchers published their findings Friday (Oct. 11) in the journal Current Biology.

Related link: ‘All it takes is a predator to learn that children are easier prey’: Why India’s ‘wolf’ attacks may not be what they seem

They conducted a genomic analysis on the hair, extracting mitochondrial DNA from four individual strands and three hair clumps. They then compared the genetic profiles to a list of potential prey species, created from previous research, to identify which species the lions may have hunted during their lifetime.

“One surprising finding was the identification of hair from wildebeest,” de Flamingh said. According to the researchers, the lions would have had to travel 56 miles (90 kilometers) to get to the closest grazing area of wildebeest (Connochaetes), which raises questions about the range of land covered by the Tsavo lions. “It suggests that the Tsavo lions may have either traveled farther than previously believed, or that wildebeest were present in the Tsavo region during that time,” de Flamingh explained.

The Tsavo lions were seen across the workers campsite that stretched eight miles (13 kilometers) of Tsavo National Park, east of mount Kilimanjaro. The size of a lion’s territory can range from 20 to 400 square miles (50 to 1,000 square kilometers), depending on the availability of prey and water. Where prey is sparse, lions will venture further to find another resource.

In the study, the researchers note that the two lions abandoned the area for several months between the attacks and it is possible that during this time they could have traveled to a more productive environment, where prey availability was higher and where wildebeest were present.

Researchers also said the absence of buffalo DNA was unexpected. Previous research from 2015 had identified a single buffalo hair from one of the lions but the metagenomic analysis in this study did not identify buffalo hair.

African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) are among the major prey animals for lions in the Tsavo region. According to the study, these two Tsavo lions may not have preyed on wildebeest because of an infectious viral disease called rinderpest that spread among split-hooved animals in the region, reducing the buffalo population. “The entry of rinderpest into Africa in the 1890s killed ~90% of cattle and had similar impacts on buffalo,” De Flamingh said.

Scientists still aren’t sure exactly why the Tsavo lions hunted humans.

Although some reports suggest these lions consumed up to 135 humans, a stable isotope analysis of the hair and bone of the Tsavo lions found that they ate around 35 humans which equates to around 35% of the diet of one lion and around 13% of the second, according to a 2017 study.

One theory suggests that the rinderpest epidemic contributed to the lions’ human-eating habit because the population of buffalo and cattle had collapsed.

Another theory suggests that this behavior may have started because of painful dental injuries found in the jaws of the two lions, which would have made catching large prey very difficult.

De Flamingh describes the layers of hair found in the Tsavo lions’ jaws as a timeline into the history of what they ate leading up to their attacks. Further analyses could enable scientists to trace changes in the lions’ diet over time and potentially shed light on when and why humans were their target.