In the last five years, the number of satellites orbiting Earth has more than doubled and will likely double again within a similar timespan, thanks to the efforts of private companies such as SpaceX. But while these spacecraft can provide important benefits, they are also causing multiple issues that are only just being realized by scientists.

So, how many satellites can we expect to see in our skies in the coming decades? And — more importantly — how many is too many?

As of May 2025, there are around 11,700 active satellites in orbit around Earth, ranging from military spy satellites and scientific probes to rapidly growing private satellite networks. But the rate at which spacecraft are being launched into space is increasing year-on-year.

The biggest contributor to this trend is SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, which currently has around 7,500 active satellites in orbit — more than 60% of the total number of operational orbiting spacecraft, Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who has been tracking satellites since 1989, told Live Science. All of these have been launched since May 2019.

However, other organizations are also beginning to develop their own “megaconstellations,” such as Amazon’s Project Kuiper and China’s “Thousand Sails” constellation. It is also getting easier to put new satellites into space thanks to the reusability of rockets, such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, which is being used to launch multiple competing satellite networks. Other companies are also exploring new ways of launching larger payloads, including shooting hundreds of satellites into space at once using a giant spinning cannon.

Related: There was nearly 1 rocket launch attempt every 34 hours in 2024 — this year will be even busier

All of this activity has left researchers wondering how many satellites could eventually end up orbiting our planet and what problems they might cause along the way.

“Megaconstellations are planning to cover most of the Earth’s surface,” Fionagh Thomson, a senior research fellow at the University of Durham in the U.K. who specializes in space ethics, told Live Science. But there is still “a large amount of uncertainty” over how large they might get and how damaging they could become, she added.

Best guess

It is difficult to estimate how many satellites will be launched in the future because satellite companies often change their plans, Aaron Boley, an astronomer at The University of British Columbia in Canada who has extensively studied the potential effects of megaconstellations, told Live Science.

“Companies update their plans as they develop their systems, and many proposed systems will never be launched. But many will,” Boley said.

Proposals for more than 1 million private satellites belonging to around 300 different megaconstellations have been submitted to the International Telecommunications Union, which regulates communications satellites, according to a 2023 study co-authored by Boley. However, some of these, including a proposed 337,000-satellite megaconstellation from Rwanda, are unlikely to come to fruition, the researchers noted.

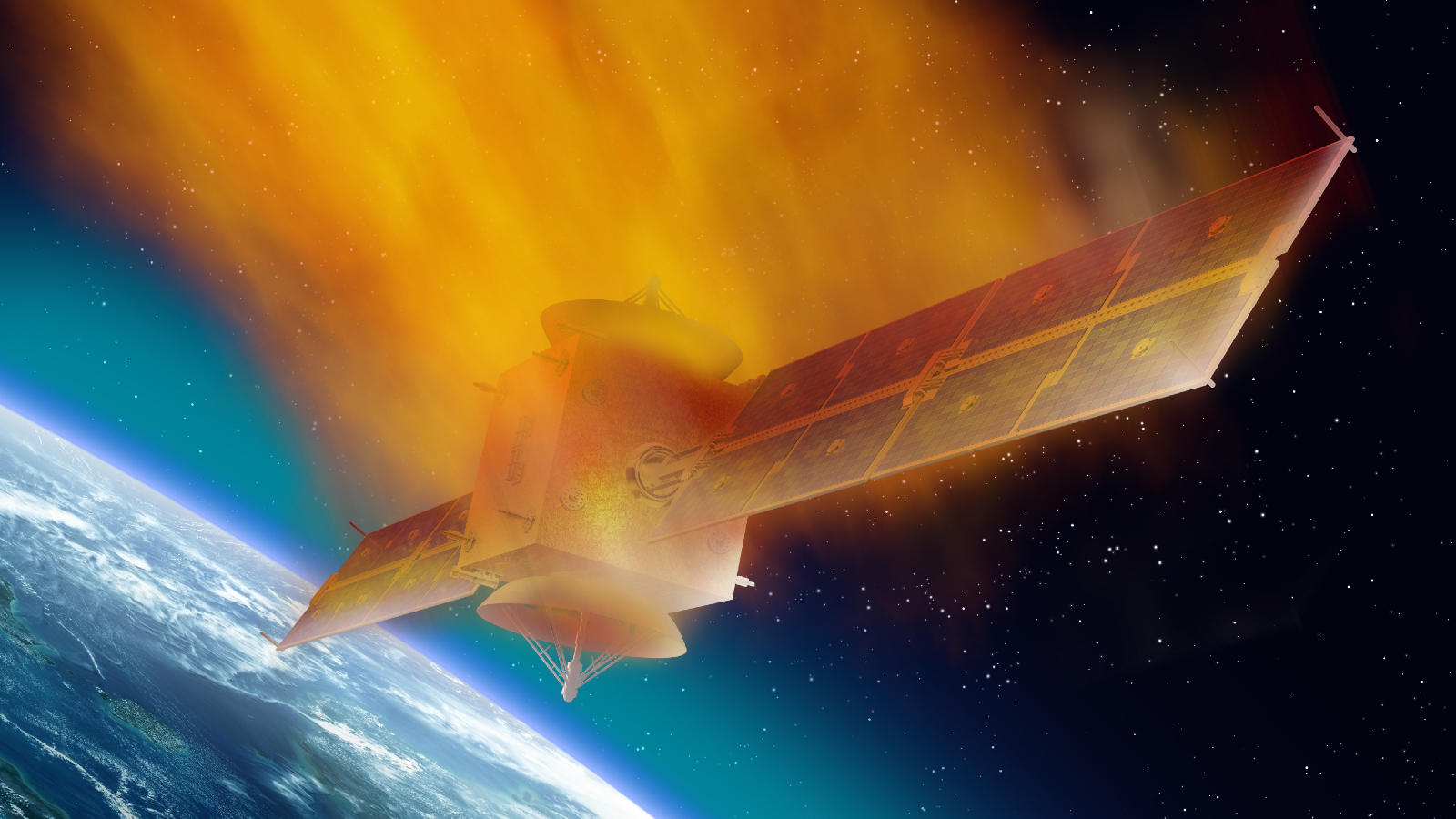

The proposed number seems massive, but most private satellites have short lifespans. For example, the average Starlink satellite spends around five years operational, after which it falls back to Earth and burns up upon reentry. So even if all 1 million proposed satellites are launched, they will not all be orbiting Earth at once.

While it is tricky to predict how many satellites will be launched and when, researchers have estimated a maximum number of spacecraft that can coexist within low-Earth orbit (LEO) — the region of space up to 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) above Earth’s surface, where a vast majority of private satellites operate. Above this upper limit, or carrying capacity, satellites would likely start constantly crashing into one another.

McDowell and Boley, as well as other astronomers — including Federico Di Vruno at the transnational Square Kilometer Array (SKA) Observatory and Benjamin Winkel at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany — all believe that the carrying capacity for LEO is around 100,000 active satellites. Above this number, new satellites will likely only be launched to replace those that come to the end of their operational lives.

It is unclear exactly when this carrying capacity will be reached. However, based on the current rate of increasing launches, several experts told Live Science that it could happen before 2050.

Mega-problems

Given the impending rise in satellite numbers, researchers are hard at work trying to figure out what problems they may cause.

A major issue associated with megaconstellations is space junk, including rocket boosters and defunct satellites, that will litter LEO before eventually falling back to Earth. If space junk collides , it could create thousands of smaller pieces of debris that increase the risk of further collisions. If left unchecked, this domino effect could render LEO effectively unusable. Researchers call this problem the “Kessler syndrome” and are already warning that it should be tackled now, before it is too late.

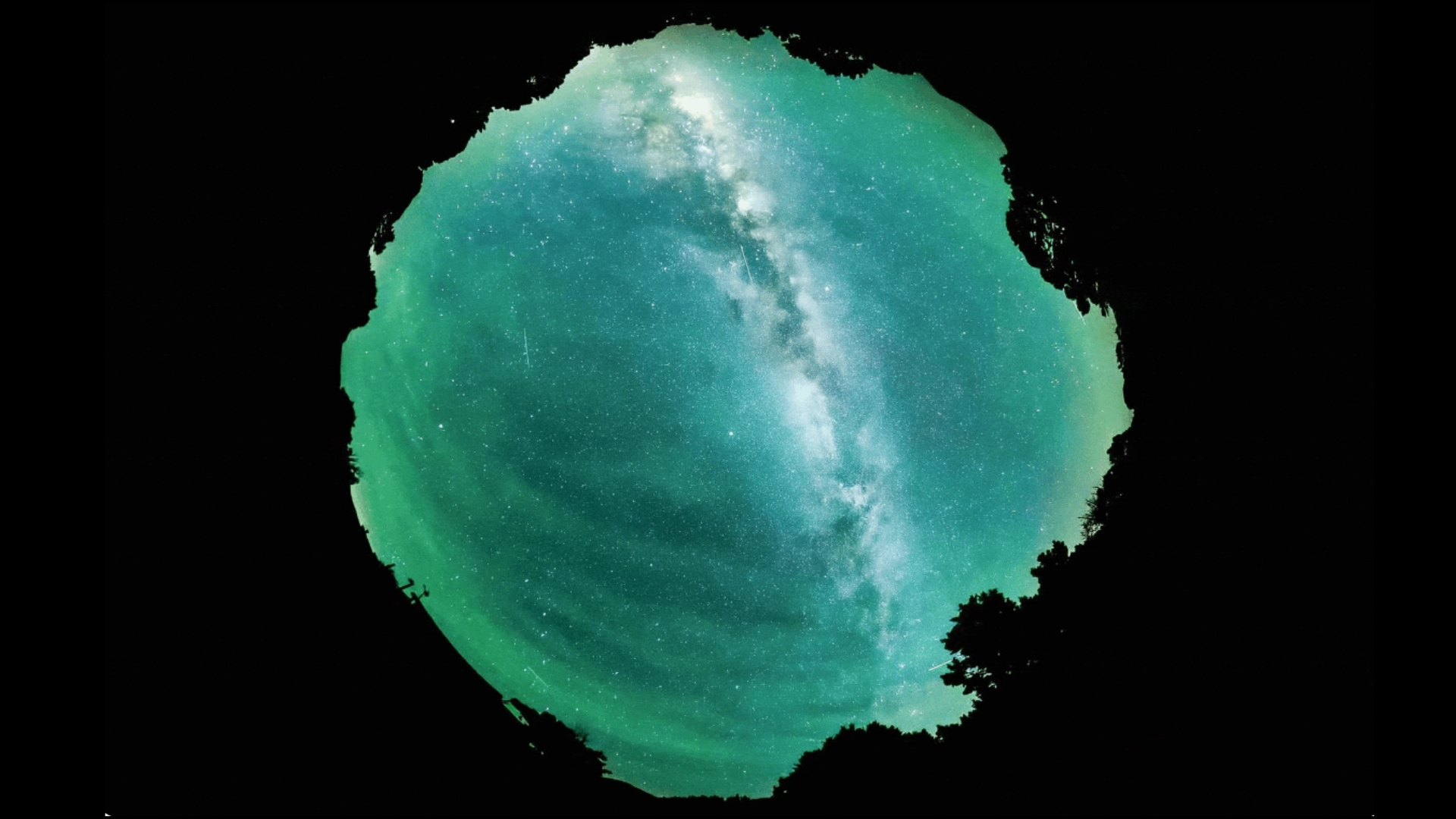

Megaconstellations also threaten to severely limit ground-based astronomy in two main ways: First, light reflecting off satellites can interfere with optical astronomy by photobombing telescopes as they pass overhead; Second, electromagnetic radiation that unintentionally leaks from communications satellites can interfere with radio astronomy by obscuring signals from distant objects, such as faraway galaxies.

If the carrying capacity is reached, some experts fear that the level of radio interference could render some types of radio astronomy completely impossible.

Related: Controversial paper claims satellite ‘megaconstellations’ like SpaceX’s could weaken Earth’s magnetic field and cause ‘atmospheric stripping.’ Should we be worried?

Satellites can also impact the environment via greenhouse gases that are emitted during rocket launches, as well as through metal pollution that is accumulating in the upper atmosphere as defunct satellites and other space junk burn up upon reentry.

Given all these potential impacts, most researchers are calling for companies to reduce the rate at which they launch satellites.

“I don’t think a full stop on satellite launches would work,” Boley said. “However, slowing things down and delaying the placement of 100,000 satellites until we have better international rules would be prudent.”

Do we need 100,000 satellites?

While private satellites help monitor Earth and connect rural and disadvantaged communities to high-speed internet, many experts argue that these benefits do not outweigh the potential risks.

Others are more skeptical and question whether the payloads being put into orbit will really do any good or if they are just a way for companies to make more money. “Do we really need another CubeSat in space that allows us to take selfies?” Thomson asked. “And in reality, does connecting remote communities [to the internet] help solve systemic issues of inequality, poverty and injustice?”

Many benefits could also be achieved with fewer satellites. The proposed numbers are so high, mainly because there are so many different companies competing to provide the same services.

“It would be better to cooperate more, in order to need fewer satellites,” Winkel told Live Science. “But I find that highly unlikely given the current situation in the world.”