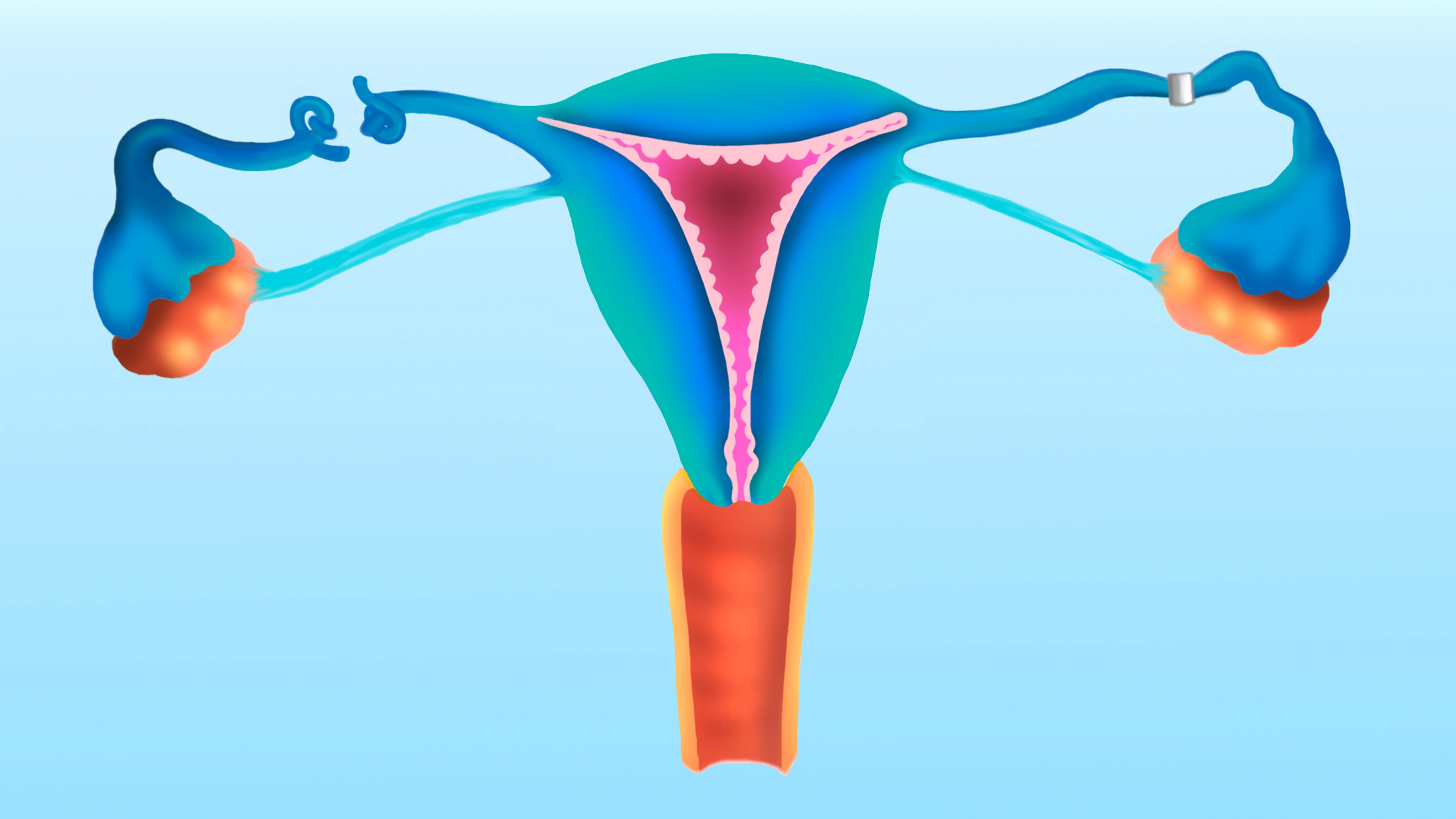

“Getting your tubes tied” is a colloquial way to say that someone is undergoing tubal ligation, a sterilizing surgical procedure that involves closing off the fallopian tubes.

In non-medically assisted pregnancy, an egg travels from the ovary to the uterus via the fallopian tubes, also called uterine tubes. Tubal ligation prevents this movement by permanently blocking, clipping or removing the tubes, thus keeping the egg from becoming fertilized. The removal of the tubes, called a salpingectomy, is a type of tubal ligation.

The procedure is extremely effective, with a 99% free-from-pregnancy rate. That number rises to 100% for surgeries that use large incisions to access the tubes, rather than minimally invasive medical tools that can navigate the body through small incisions.

“It’s a great option for family planning that does, unfortunately, involve a surgical procedure,” Dr. Andrew Rubenstein, director of General Obstetrics and Gynecology at NYU Langone Health, told Live Science.

Side effects are minimal, but can include shoulder pain, bloating, abdominal cramping, nausea and dizziness, according to Cleveland Clinic. The shoulder pain is related to gas used to temporarily inflate the abdomen during some tubal ligation procedures; that gas can linger and irritate the neck, shoulders and chest for up to a couple days after surgery.

Tubal ligation can be performed whether or not the patient has had a pregnancy previously, Rubenstein explained.

Related: Tube-tying surgeries and vasectomies skyrocketed post-Roe

Regardless of when a person gets their tubes tied, extensive consultation between the patient and the physician is required beforehand. The patient’s partner may also be included in the consultation, if applicable.

“It is shared decision making amongst the team members,” Rubenstein said, describing the process of deciding what form of birth control is the best approach for each individual patient. “It’s not a single episode event and then surgery is scheduled. It does require some doctor-patient relationship.”

How does the surgery work?

There are four main methods for completing a tubal ligation, each using a different technique to block the travel of an egg. Doctors may remove both tubes completely — which is called a bilateral salpingectomy, or “bisalp” for short — or partition the tubes by cauterizing, clipping or folding them.

(Unilateral salpingectomies, which remove only one tube, are not a sterilizing procedure but can be used to treat conditions like ectopic pregnancy.)

The method a physician chooses, and whether they agree to carry out the procedure at all, in part depends on a patient’s clinical history, Rubenstein said. Doctors will consider factors like age, past surgical procedures and body mass index to see what’s feasible for a given patient.

The procedure is often completed through two small incisions, one just below the navel and the other on the lower abdomen above the pelvis. Using laparoscopic tools — a small camera and accompanying instruments that allow the surgeon to see within the body — the physician can complete the permanent operation.

Sometimes a tubal ligation is performed as a preventative treatment to decrease a patient’s chances of contracting ovarian cancer. Evidence suggests that ovarian cancers often arise in the fallopian tubes, and that removing the tubes can cut the risk.

“It doesn’t eliminate it, but it definitely reduces that risk for patients,” Rubenstein said. It’s currently unclear by how much tubal ligation lowers the odds of developing ovarian cancer, but some research suggests it decreases by 24% to 42%.

Anyone with fallopian tubes who is uninterested in getting pregnant in the future and already plans to undergo pelvic surgery should consider taking this preventative measure simultaneously, the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology suggest.

Rubenstein warned that not all operating rooms will perform tubal ligations. “Certain organizations will not allow you to do tubal ligation in their facilities based on religious beliefs, so they have to be done then in a nondenominational facility,” he said.

Is it permanent?

Like any operation, tubal ligation can fail — in this context, failure means the patient becomes pregnant after the surgery.

“It’s extremely rare,” Rubenstein said, but it can happen and is more likely to occur for younger patients. Within the first year after the procedure, the failure rate is estimated to be 0.1 to 0.8% across all patients.

Some providers won’t perform the procedure on someone younger than 30, Rubenstein said, on the basis that the patient might later come to regret it. One 2022 study that surveyed about 1,500 patients found that 12.6% of people who underwent sterilization at ages 21 to 30 and 6.7% of those who underwent sterilization when they were older than 30 regretted their choice. Notably, the majority of the patients — 92% — were in the over-30 group, so the sample of under-30s was somewhat small.

To place the 2022 study in greater context, the average regret rate reported is similar to that for knee replacement surgery, at around 10%.

Rubenstein thinks it is important to emphasize that tubal ligation is a permanent surgery. “People have a misconception that tying your tubes is similar to tying your shoelaces. You can tie and untie them,” he said.

While it is medically possible to reverse the operation when the tubes have not been fully removed, just cauterized, clipped or folded, most doctors won’t do so, Rubenstein said. When they are done, reversal surgeries enable about 73% of patients to get pregnant and 53% to give birth, a review of 135 cases found.

In contrast, Rubenstein described in vitro fertilization (IVF) success rates in such situations as “exceptional.” In other words, “we would recommend to that patient to have an IVF cycle and then a transfer of that embryo into the uterus rather than trying to reconnect the tubes.” IVF never requires an egg to travel through the tubes, so the procedure would still work for a person lacking tubes.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.