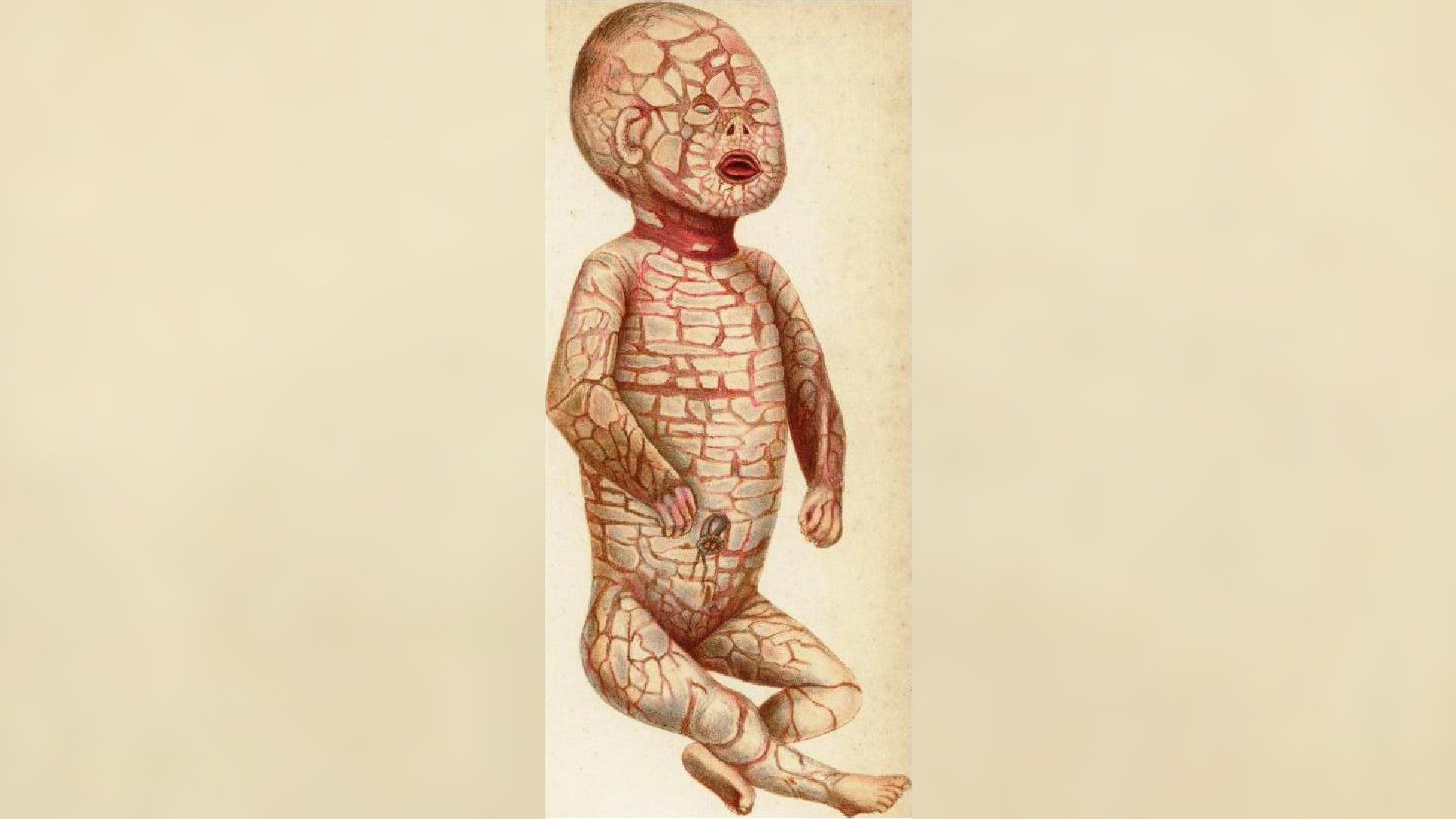

Disease name: Harlequin ichthyosis, also called ichthyosis fetalis and harlequin baby syndrome

Affected populations: This genetic condition affects an estimated 1 in 300,000 live births globally. In the United States, it’s estimated to occur in about 1 in 500,000 births, or about seven births a year, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders. The condition seems to affect males and females in equal numbers and doesn’t occur in greater frequency in any specific racial or ethnic group.

Causes: Harlequin ichthyosis is caused by a variety of mutations in a gene called ABCA12, which carries instructions for proteins that ship molecules across cell membranes. These proteins are key for transporting fats and enzymes in the outermost layer of the skin, known as the epidermis.

Most people with harlequin ichthyosis carry a genetic mutation that causes cells to make ABCA12 proteins that are too short and thus unable to properly transport fats. In some cases, people can’t make the protein at all, which results in the most severe cases of the disease.

Evidence suggests that the condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, meaning a baby must inherit two copies of the broken gene — one from each parent — to develop the disorder. People with only one mutant copy of the gene are “carriers” but do not show symptoms. People with a family history of the disorder can consider seeking genetic counseling to see if they’re a carrier.

Symptoms: The transportation of fat molecules in the epidermis is important for keeping the skin hydrated, and it’s also necessary for the skin to develop properly in the womb and after birth. When babies have ABCA12 proteins that are too short or totally absent, these infants are born with thick, platelike scales of skin, which cause the skin to be stretched very tightly.

The tight skin cracks easily, forming fissures. The tension pulls at the affected baby’s eyelids and lips, turning them inside out, and it also constricts the movement of the chest, which impedes breathing and eating. Poor nail and hair growth are also common.

Babies with harlequin ichthyosis are often born prematurely, and they may also show additional symptoms and traits, such as a flat nose, abnormal hearing, ears that are fused to their head, swollen hands and feet, and decreased joint mobility.

The condition compromises the skin’s protective barrier, leaving the infant vulnerable to dehydration and unable to regulate their temperature or fight infections well. For infants that survive the newborn period, the “armor-like” plates eventually shed and the remaining skin is very red, dry and scaly.

Infants with harlequin ichthyosis often don’t survive the newborn period, but with intensive medical care, it’s possible for them to survive to later infancy, childhood and even early adulthood, in some cases. A report that reviewed 45 cases of the disease found that about 55% of the patients survived the newborn period, with survivors ranging from 10 months to 25 years old at the time of survey. Common causes of death in the period shortly after birth included respiratory failure and/or sepsis, a dangerous body-wide immune response.

Treatments: There is no cure for harlequin ichthyosis, so care aims to manage the symptoms of the disease.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, babies with the condition are cared for in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) immediately after birth. There, they can be placed in high-humidity incubators to help regulate their temperature and skin hydration. They’re also bathed often to soften and loosen the skin plaques, and exfoliating techniques might be used to help remove the scales. Moisturizers and skin barrier repair formulas can also help with the excessive skin dryness and stiffness. Various pain relievers can help make newborns more comfortable.

In severe cases, medications called retinoids may be used and are typically given orally. These drugs help to break down the thick, platelike scales covering the skin, which, in turn, may reduce other symptoms of the condition. However, these medications are conserved for severe cases because they can have toxic side effects if used over the long term.

Antibiotics may be needed to prevent or counter skin infections. The eyes should also be lubricated regularly, as infants with the condition cannot close their eyelids properly.

Once discharged from the NICU, children with harlequin ichthyosis require ongoing skin care, as well as lifelong medical care to manage additional symptoms that may emerge due to their condition. This care usually requires a diverse team of medical specialists, including ophthalmologists, plastic surgeons, nutritionists, physical and occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.