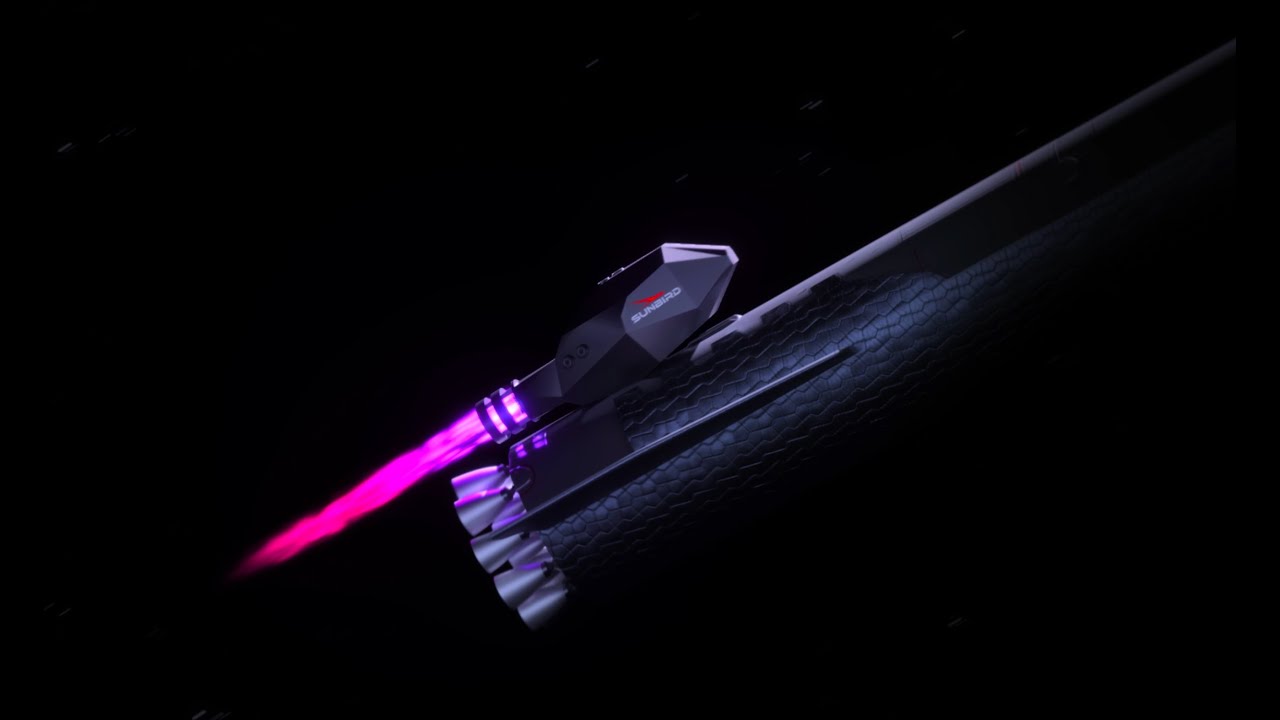

A U.K. start-up has shocked the space exploration community after unveiling plans to use a novel nuclear fusion propulsion system to power an orbital fleet of reusable “alien-like” rockets, known as Sunbirds, which the company says could revolutionize how we explore the solar system — and beyond.

The technology behind this ambitious project will begin testing this year and could make it into space by 2027, Richard Dinan, the founder and CEO of Pulsar Fusion, which is making the rockets, told Live Science. However, the company has set no timeline for when the futuristic spacecraft could become a reality. One expert told Live Science it could be at least a decade away, if not more.

Pulsar Fusion, which also makes traditional plasma thrusters and is developing nuclear fission engines, first announced the Sunbird project on March 6 after developing the concept in “complete secrecy” over the last decade, according to a statement emailed to Live Science. The project was then fully revealed to the public on March 11 at the Space-Comm Expo in London’s ExCel center.

In theory, the proposed rockets will be stored in massive orbital satellite docks before being deployed and attached to other spacecraft and rapidly propelling them to their destinations like giant “space tugs,” which would massively reduce the cost of long-haul space missions.

A concept video shows how the futuristic rockets could be used to transport a larger spacecraft to Mars and back using docking stations at both ends of the journey (see below).

Related: How do space rockets work without air?

The Sunbirds’ core technology is the Duel Direct Fusion Drive (DDFD) engines, which the company claims will harness the elusive power of nuclear fusion and, hypothetically, provide exhaust speeds much higher than those currently possible.

If it works, this could cut the potential journey time to Mars in half and allow probes to reach Pluto in 4 years, according to Pulsar Fusion. (The current record for a trip to Pluto is 9.5 years, which was set by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft in 2015.)

“If we are going to be the species that actually get to other planets, then exhaust speeds are pretty much the most important thing,” Dinan said during a talk at Space-Comm Expo. “In terms of what can be [theoretically] produced in exhaust speeds, fusion is king.”

Watch On

Fusion in space

On Earth, using nuclear fusion as a source of near-limitless energy is still likely decades away, which at first glance makes the idea of fusion rockets seem like pure science fiction. However, the opposite is true because “the bar is lower for fusion in space,” Dinan told Live Science in an interview at Space-Comm Expo.

That’s because the proposed reaction needed in space is different from what physicists are attempting on Earth. In traditional nuclear fusion reactors, known as tokamaks, the goal is to fuse deuterium and tritium — both heavy isotopes, or versions, of hydrogen — in order to emit a constant stream of neutrons, which generates heat (and in turn energy), as well as breeding more fuel for the continued reaction.

However, the planned fuel for the DDFD is deuterium and helium-3, an extremely rare isotope of helium with one less neutron than the dominant form. In this case, the reaction would pump out protons, and their charge can be used for direct propulsion. Additionally, the proposed reaction would only need to last for short periods at a time, similar to the timescales already achieved on Earth.

The shape and scale of the reactor are also important. Tokamaks are large doughnut-shaped chambers that must mimic the vacuum of space and withstand sustained temperatures equivalent to the surface of the sun. To do so, they use extremely powerful electromagnets to confine plasma into a constant loop. But the DDFD is a linear reactor that does not need to fully constrain the plasma within. In space, there is also a natural vacuum and temperatures reaching absolute zero, which will prevent the reactor from overheating.

However, the designs of the DDFD are still a closely guarded secret and have not yet been properly tested, so their exact workings and feasibility are unclear.

Dinan said he understood why people might be initially skeptical of the feasibility of fusion in space but added that when people look at it logically it starts to make a lot of sense. “This is in every way achievable,” he added. “If we can do fusion on Earth, we can definitely do fusion in space.”

But not everyone agrees that it will be so easy.

“I’m skeptical,” Paulo Lozano, an astronautics professor at MIT who specializes in rocket propulsions, told Live Science in an email. “Fusion is tricky and has been tricky for many reasons and for a long time, especially in compact devices.” However, without seeing the full Sunbird designs, he added that he has “no technical basis to judge.”

Sunbirds are go

If Pulsar can master the DDFD, the plan is to use the resulting Sunbirds as “space tugs” that can propel any spacecraft from low-Earth orbit (LEO) further into space — largely because fusion is not a viable or safe way of launching rockets directly from Earth’s surface.

So rather than having to build giant rockets with massive thrusters in order to completely escape Earth’s gravity, as SpaceX’s temperamental Starship rocket does, sunbirds will allow any spacecraft that makes it into LEO to escape our planet’s pull. This would make missions to the moon, Mars and beyond much more feasible — and cheaper, Dinan said.

Pulsar also envisions the Sunbirds acting as a battery that can power the systems of any spacecraft it is attached to during the journey. Although this is not the primary goal.

Related: 10 times space missions went very wrong in 2024

Another big draw of the Sunbirds is that they would only require small amounts of fuel and could be easily refilled and recharged while they are “perched” on their orbital docking stations, potentially making them much more reusable than most other propulsion systems, Dinan said.

The Sunbirds will likely be around 100 feet (30 meters) long and were described as having a “distinctive alien-like design” in the initial press release. This is due to thick “tank-like” armor plating that will hopefully allow them to survive being bombarded with cosmic radiation and micrometeorites in space, which is why they look “super weird,” Dinan said.

Each Sunbird could cost upwards of $90 million (70 million British pounds) to produce, largely because of how expensive helium-3 is to obtain, Dinan estimated. However, the amount of money that these rockets could save a potential client means they would be well worth the cost, he added. “If I can get them there quicker, they will pay for it.”

In the future, helium-3 could be mined from regolith on the moon, which would be much cheaper than trying to produce it on Earth, Lozano said. But this is not currently part of Pulsar’s plans.

Next steps

Pulsar will conduct the first static tests of the DDFD engine this year inside a pair of giant vacuum chambers recently constructed at the company’s campus in Bletchley, England. These chambers are the largest of their kind in the U.K. and possibly the largest in Europe, Dinan said.

These initial tests won’t use helium-3 because it is too expensive to obtain for use in a prototype, meaning that true fusion will not be achieved. Instead, an “inert gas” will be used in its place to test how the engine could theoretically work, Dinan said.

Next, Pulsar Fusion plans to undergo an orbital demonstration for some of the “key technological components” in 2027, he added. However, Dinan didn’t clarify what this will entail.

If the upcoming tests are successful, Pulsar will begin to raise funds to build a full-scale Sunbird prototype and begin trying to achieve true fusion using helium-3. However, Dinan says that there is no timeline for creating the first Sunbird prototype and it is “too speculative” to predict when this may happen.

Lozano “optimistically” predicts that a fully operational Sunbird prototype is at least a decade away but added that physicists often joke that “fusion is 20 years in the future and always will be.”