Ozempic-like drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity may also treat migraine, even when the medications don’t trigger weight loss, early research suggests.

A preliminary report, published in the journal Headache and presented June 21 at the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) conference, suggests that liraglutide — a drug used to treat obesity and diabetes — slashed the number of days patients experienced severe migraines by almost half. Liraglutide belongs to a class of drugs called GLP-1 agonists, which also includes semaglutide, the active ingredient in the diabetes drug Ozempic and weight-loss drug Wegovy.

But while the idea of treating migraines with these drugs is “extremely innovative and forward-thinking,” the new results should be taken with caution. That’s because the trial was small and didn’t include a comparison group that didn’t use the medication, Dr. Alex Sinclair, a neurologist at the University of Birmingham in the U.K. who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science.

“This is an absolutely tantalizing research study because it gives us a really interesting idea of a new mechanism of delivering drugs for migraine,” Sinclair told Live Science. “But it is very preliminary.”

This “very important and exciting finding” could potentially provide “another treatment option for patients with chronic migraine, especially for those who did not previously respond to other current available treatments,” said Dr. Chia-Chun Chiang, an associate professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota who wasn’t involved in the study.

Migraine days cut in half

To assess the effect of liraglutide on migraine, Dr. Simone Braca, a neurologist at the University of Naples Federico II in Italy, and colleagues gave 31 patients with obesity and high-frequency or chronic migraine 0.6 milligrams of liraglutide daily for one week, followed by 1.2 mg daily for the next 11 weeks.

After 12 weeks, nearly half of the patients reported that their number of headache days per month had dropped, from an average of 20 to nine. This was a “huge” effect, Braca told Live Science.

Seven people saw their headache days drop by 75%, and one patient’s migraines disappeared completely. Overall, the patients also reported a large drop in how much migraine impeded their daily lives. Importantly, the participants did not shed weight during the study. This suggests the improvement in migraine wasn’t linked to weight loss, a noteworthy observation since obesity is known to increase the risk of severe headaches.

Related: Can weight loss drugs help you drink less alcohol?

Braca highlighted that these patients had been selected because they had not responded to other migraine drugs, such as antibodies that target calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a molecule released in the brain during a migraine.

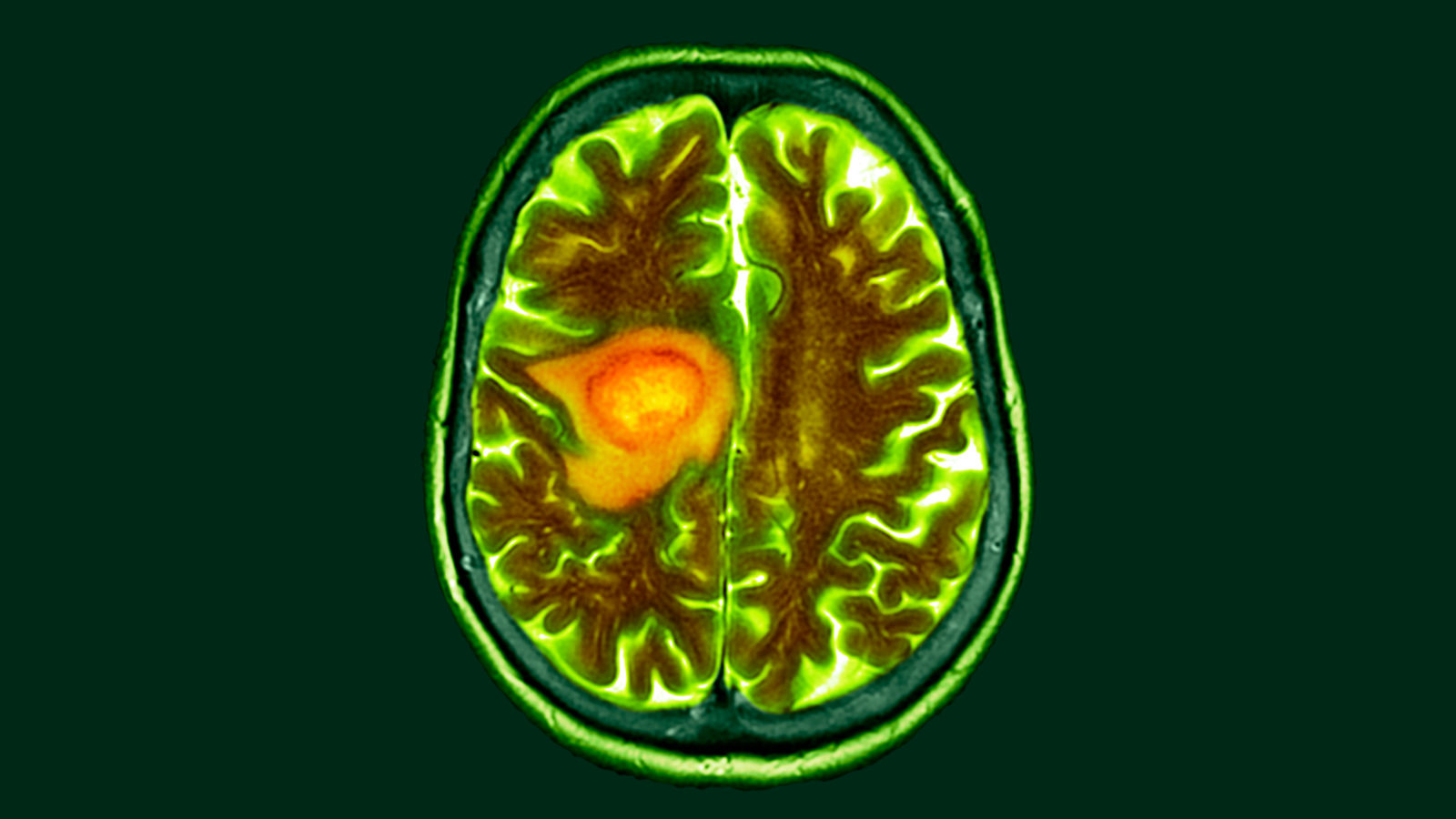

The study authors have some theories about what might be happening, but they didn’t collect measurements that could prove a mechanism of action. GLP-1 drugs may reduce pressure inside the skull by lowering the production of cerebrospinal fluid, which bathes the brain and spinal cord, the researchers suggested. This, in turn, could reduce the release of CGRP, which many scientists think fuels migraine pain.

In support of that hypothesis, Braca’s team pointed to a previous study led by Sinclair and published in the journal Brain in 2023. It suggested that exenatide, another GLP-1 drug, lowers brain pressure. Of note the drug seemed to reduce migraine days among the study participants, although it was unable to show a strong statistical difference.

Other possible mechanisms underpinning the effect in the new study results could be that liraglutide directly reduced the release of CGRP or that the drug regulated glucose metabolism, Chiang said. Previous research has suggested that migraine could be linked to issues in glucose metabolism.

The new study has important limitations, though, Sinclair said. First, the study was very small, with only 31 participants, and it lasted only 12 weeks. Another significant limitation is that the trial did not include a placebo group. The placebo effect, by which people’s symptoms improve even with a sham treatment, is particularly strong when it comes to self-reported pain.

“We have a big placebo response in headache research,” Sinclair told Live Science.

Braca agreed that the trial had limitations. Still, “both the history of multiple previous treatment failures and the magnitude of the observed response reduce the likelihood of a significant placebo effect,” Braca said.

The results now need to be confirmed in larger, placebo-controlled clinical trials before they could guide treatment for patients with migraine. If confirmed, however, the findings could open up a new line of inquiry for migraine treatment, Braca said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.