The patient: A 34-year-old man named Brent Chapman in British Columbia, Canada

The medical history: When Chapman was 13 years old, he had a rare and serious autoimmune reaction after taking a normal dose of ibuprofen. This reaction, known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, trips the immune system, causing cells to attack the skin and mucus membranes. In this case, the syndrome caused severe burn-like injuries all over Chapman’s body, including the surfaces of his eyes.

His left cornea — the transparent dome that covers the eye — was destroyed when one of these injuries became infected, and he lost most of the vision in his right eye due to corneal damage.

Over the next two decades, Chapman had more than 50 surgeries — including 10 attempts at corneal implants in his right eye — but most were unsuccessful. Some of the surgeries temporarily restored partial vision, but none could permanently restore his sight.

What happened next: Doctors proposed a surgical procedure called osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis, or tooth-in-eye surgery, to restore vision in Chapman’s right eye. The technique has been around since the 1960s but had never before been performed in Canada before Chapman’s case.

The procedure involves removing one of the patient’s teeth and then implanting it in their eye socket, where it serves as a platform for a transparent, plastic lens. The lens stands in for the injured cornea and enables light to enter the eye.

Candidates for tooth-in-eye surgery typically have damaged corneas and a healthy retina and optic nerve — meaning the light-sensitive tissues and nerves at the back of the eye still work well. According to a 2022 study of 59 patients who underwent tooth-in-eye surgery, 94% showed long-term vision retention, based on follow-up visits spanning 30 years.

The treatment: Dr. Greg Moloney, a clinical associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of British Columbia, performed the first stage of the operation on Chapman and two other Canadian patients in February 2025.

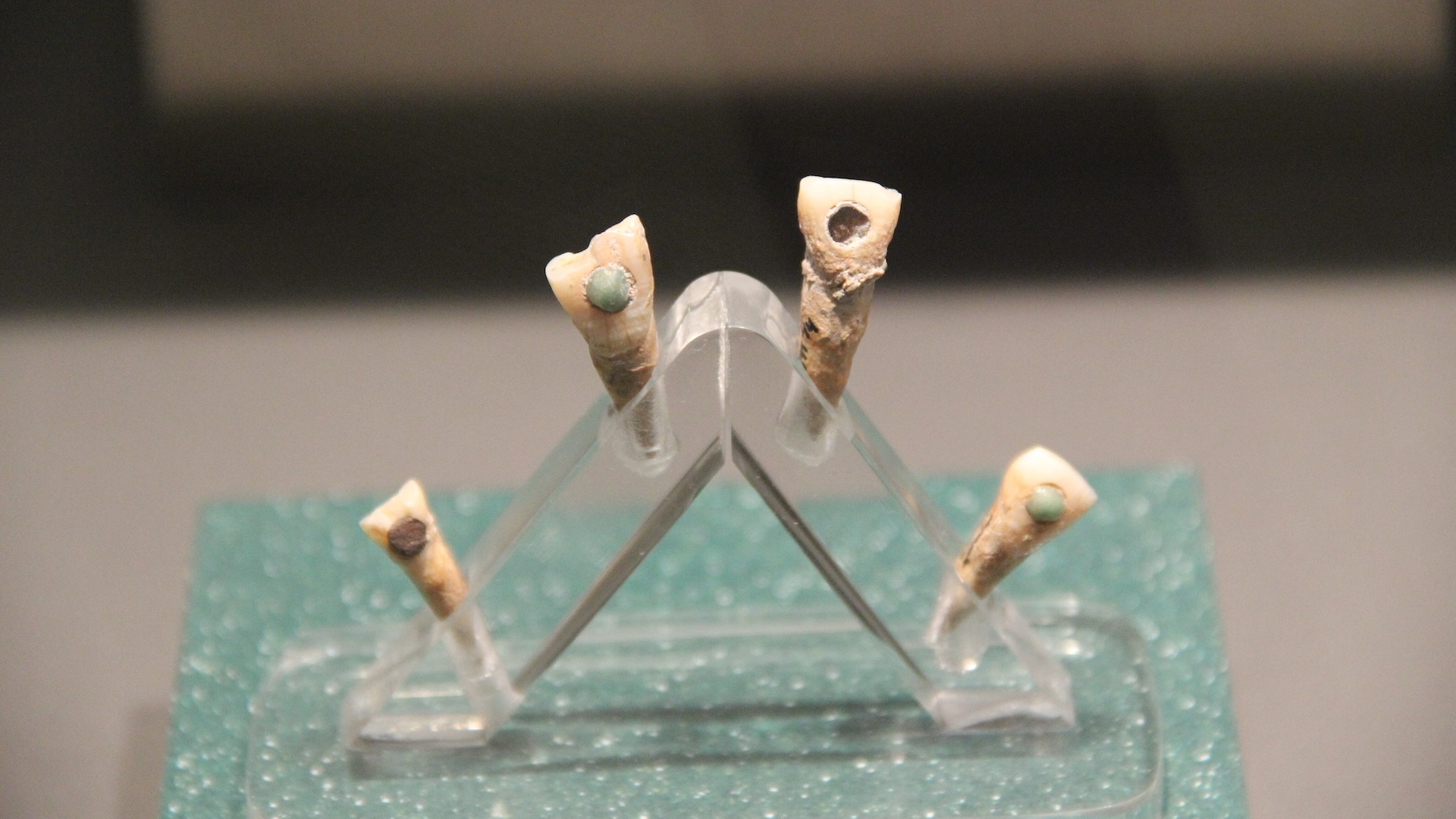

Moloney first removed one of Chapman’s canine teeth, as well as a thin layer of the bone that had been surrounding it. This kept the tooth supplied with blood and oxygen. The tooth was then shaved flat, into a small block, before being drilled and fitted with a lens-holding plastic cylinder. The sculpted tooth was then implanted in Chapman’s cheek to enable soft tissue to grow around it for several months.

Then, in June, the tooth was removed and surgically implanted in Chapman’s right eye. Because the tooth and surrounding soft tissue come from the patient, their body is less likely to reject a tooth-in-eye implant.

Almost immediately after the surgery, Chapman could perceive movement. His vision gradually sharpened over the next month, though there was some visual distortion, and he had another surgery in August to correct the lens placement. Later that month, tests with corrective glasses showed that he had 20/30 vision; objects that are visible at 30 feet (9 meters) for a person with perfect vision were in focus for Chapman at 20 feet (6 meters).

What makes the case unique: Tooth-in-eye surgery is considered a last resort for blindness caused by corneal damage. The multipart operation takes more than 12 hours, not counting the time that tissue grows around the tooth in the cheek, and there are few specialists who perform it worldwide.

Doctors have previously performed tooth-in-eye surgery in Australia, Chile, Egypt, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. To date, only several hundred people have received the procedure.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.