“Chemo brain” — chemotherapy-induced difficulties with focusing, thinking and remembering — may be caused by the cancer treatment’s disruption to the brain’s lymphatic system, an early-stage study suggests.

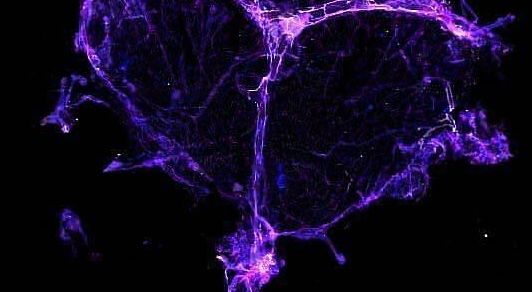

The study zoomed in on the meningeal lymphatics, the drainage network found in the protective tissue layer surrounding the brain. Dysfunction in this network has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and traumatic brain injuries.

Using human and mouse cells, as well as living lab mice, researchers found evidence that a common type of chemotherapy drug that blocks cancer cells from dividing, called taxanes, damages the brain’s lymphatic vessels and limits their drainage. Normally, the vessels would work together with the brain’s glymphatic system to flush away metabolic waste.

“Lymphatic health really declined across all three models measured in different ways,” study co-author Jennifer Munson, director of Virginia Tech’s Cancer Research Center in Roanoke, Virginia, said in a statement. The vessels shrank and had fewer branches, which “are signs of reduced growth that indicate the lymphatics are changing, or not regenerating in beneficial ways,” she said.

“Chemo brain” is a broad category of cognitive changes that follow chemotherapy and can last for years after treatment. “There’s really a lot we don’t know,” Munson told Live Science, but these cognitive impairments have previously been linked to oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as impaired myelin production. (Myelin is fatty insulation that covers nerve fibers.)

“Others had looked on the neural side, so we wanted to focus on the meningeal side,” Munson said.

To do this, Munson and her team used three models — human cells, mouse tissues and live mice — to assess whether chemotherapy drugs led to changes to the meningeal lymphatics at different scales.

First, they used cell lines to build a human-cell model of healthy meningeal lymphatics. This model paired cells from the lining of lymphatic vessels with meningeal cells. This enabled the team to tease apart the isolated effects of chemo on each cell’s function. They also grew healthy mouse meningeal tissue in lab dishes to assess any structural changes triggered by the drug exposure.

They found that the drug docetaxel disrupted the cells in the human meningeal lymphatic model by reducing their coverage and length. The treatment also shrank the vessels within the mouse tissues and reduced the number of loops in the network structure.

Next, the researchers ran experiments with live mice, comparing mice treated with docetaxel to mice unexposed to the drug. Mice with cancerous tumors that were given the drug tended to have narrower meningeal lymphatic vessels, as well as fewer loops, compared to untreated mice.

The researchers wanted to see whether these docetaxel-induced structural changes led to impaired memory or changes in behavior. They found that healthy mice treated with docetaxel forgot objects they had previously seen, while the untreated mice showed clear signs of remembering them. MRI scans of the treated mice indicated that these cognitive issues correlated with the decreased flow of fluids through the lymphatic vessels, the authors wrote in the study.

Munson cautioned that this is an early-stage study and that there are many gaps left in our understanding of the link between “chemo brain” and meningeal lymphatics. She explained that one limitation of the research was that the chemotherapy drugs were administered over relatively short time periods, whereas chemotherapy courses for human cancer patients often last months.

Similarly, the memory issues the mice experienced were tested over a couple of days, whereas humans can sometimes experience chemo brain for years following treatment. “So it’s possible that these lasting effects that we see in [human] patients may have different mechanisms that may not be captured fully here,” Munson said.

It is important to replicate this research using samples from many individuals of different ages and to compare outcomes between tumor-bearing and tumor-free mice, to see if there’s a difference in how the chemotherapy affects them, Munson said. She hopes that, eventually, this research will provide a new target for treating this side effect of chemotherapy.

“Ultimately, this work underscores the need to consider not only survival, but also the long-term, often overlooked neurological side effects of cancer treatment on cognitive well-being and quality of life,” study co-author Monet Roberts, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and mechanics at Virginia Tech, said in the statement.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.