Digestive gas gets the best of everyone sooner or later, often in the form of a burp. Burping is how the body clears excess gas from the upper digestive tract, which would otherwise result in extremely uncomfortable pressure in your stomach and esophagus.

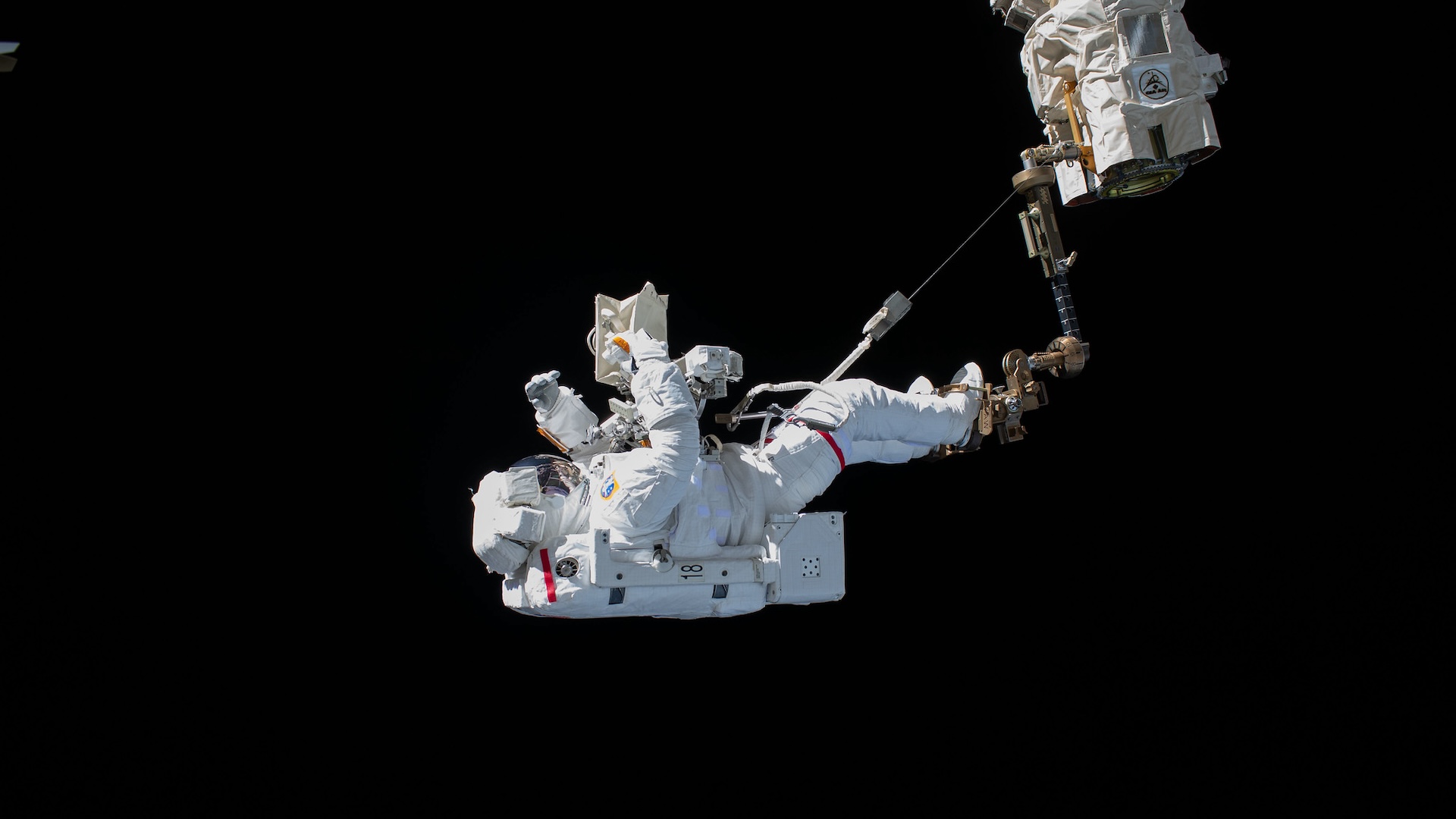

Or at least that’s how it works on Earth. In space, everything works a little differently without gravity to help. So is it true that you can’t burp in space? The answer is messier than you might expect.

You can’t burp in microgravity the way you would on Earth, experts told Live Science. That’s because, unlike vomiting, which uses the muscles of your digestive tract to force food back up, the mechanics of burping depend completely on gravity. First, gravity helps separate the gassy ingredients of a burp from the liquid and solid remnants of food in the stomach; gas is lighter and thus floats to the top. So, before you burp, the stomach contains a layer of hot, sometimes smelly gas hovering above a swampy mix of partially digested food.

When enough gas builds up, it puts pressure on the sphincter (a ring of muscle that acts as a barrier between parts of the digestive system) between the esophagus and the stomach; the sphincter opens and lets the gas rise into the lower part of the esophagus. A second sphincter, farther up, allows the rising gas into the upper esophagus, where it can escape as a burp.

“In space, air and liquids in the stomach can’t separate like on Earth,” Raffi Kuyumjian, chief medical officer of Operational Space Medicine at the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), told Live Science. Without gravity to sort out the contents of your stomach, it’s all just one big chunky, gassy mess. In space, as on Earth, you can force yourself to burp by chugging a carbonated drink, gulping air and holding it in, and moving your abdominal muscles — but if you do it while floating in microgravity, it’s going to be, as astronaut Chris Hadfield described it in a 2018 post on Twitter (now X), “chunky bubbles.”

Related: What happens when you hold in a fart?

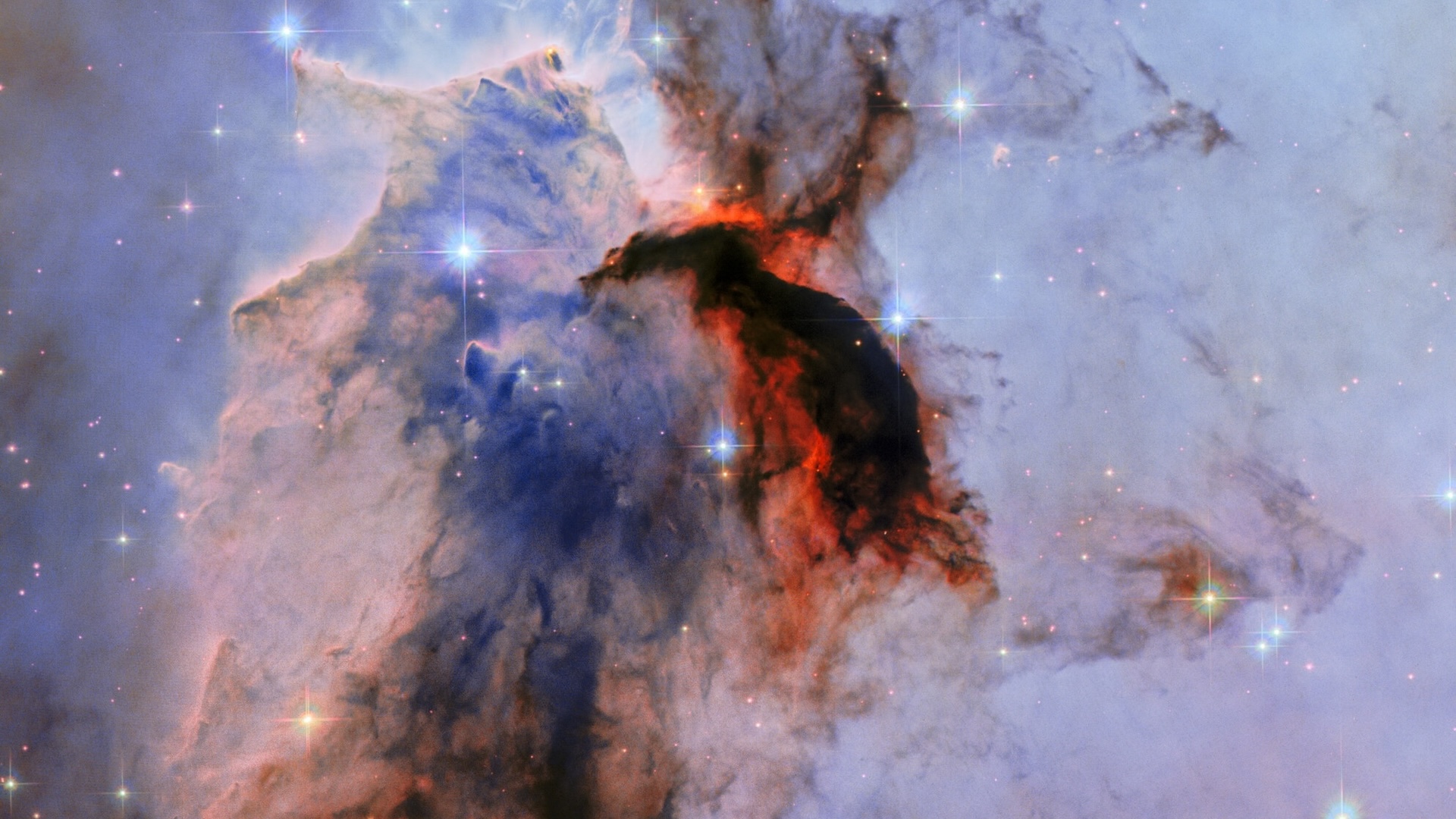

Gravity also helps the burp escape, thanks to a process called convection. When a gas or liquid is heated, its molecules spread out, making it less dense (and therefore lighter) than the surrounding gas or liquid. That’s why you see columns of bubbles rising in a pot of boiling water, why the sun’s surface is covered with convection cells, and why the hot gas of a burp inevitably rises from your stomach, back up your esophagus, and out through your (hopefully politely covered) mouth.

However, without gravity, convection doesn’t work. If there’s no gravity pulling on the contents of your stomach, it doesn’t matter if some components of an astronaut’s lunch are heavier or lighter than others.

“There’s no up or down in weightlessness, so gas can’t ‘rise’ from the stomach for burping,” Kuyumjian said.

The good news is that astronauts don’t have to worry about a badly timed belch sneaking out in the middle of an otherwise quiet workday. Adrianos Golemis, human spaceflight surgeon for the European Space Agency and the French space agency CNES, when asked about the physiology of burping in space, said “it’s never come up in a post-flight debrief.” (The pun may or may not have been intended.)

Some may face a different potential problem, though: “Instead of burping, astronauts may experience a reflux of stomach liquids and gas,” Kuyumjian said. Reflux happens when the sphincter between the stomach and the esophagus relaxes, allowing stomach acid (and sometimes partially-digested food) back into the esophagus. It can be painful, and some people respond by swallowing more to try to clear the irritating acid from their throat — which, ironically, makes burping more likely.

In space, because liquids, solids and gases are all mixed up in the astronaut’s stomach, liquid is as likely to come back up as gas. Floating in microgravity erases the line between reflux and burping.

If an astronaut absolutely has to try burping in space but doesn’t want to belch out a mix of stomach fluids and partially chewed food, there’s another way to do it: creating your own artificial gravity, astronaut Jim Newman told author Ariel Waldman in the book “What’s It Like in Space?: Stories from Astronauts Who’ve Been There” (Chronicle Books, 2016). Give yourself a good shove away from a nearby wall, and the acceleration should mimic the effects of gravity, temporarily sorting out your stomach contents. But timing is everything, because you need to make yourself burp while you’re still accelerating away from the wall — otherwise you’ll get chunky bubbles.

Gas that makes it past the stomach and into the intestinal tract can come out the other end as a fart, which is an entirely different challenge.