A huge “wave” is rippling through our galaxy, pushing billions of stars in its wake, a new study reveals.

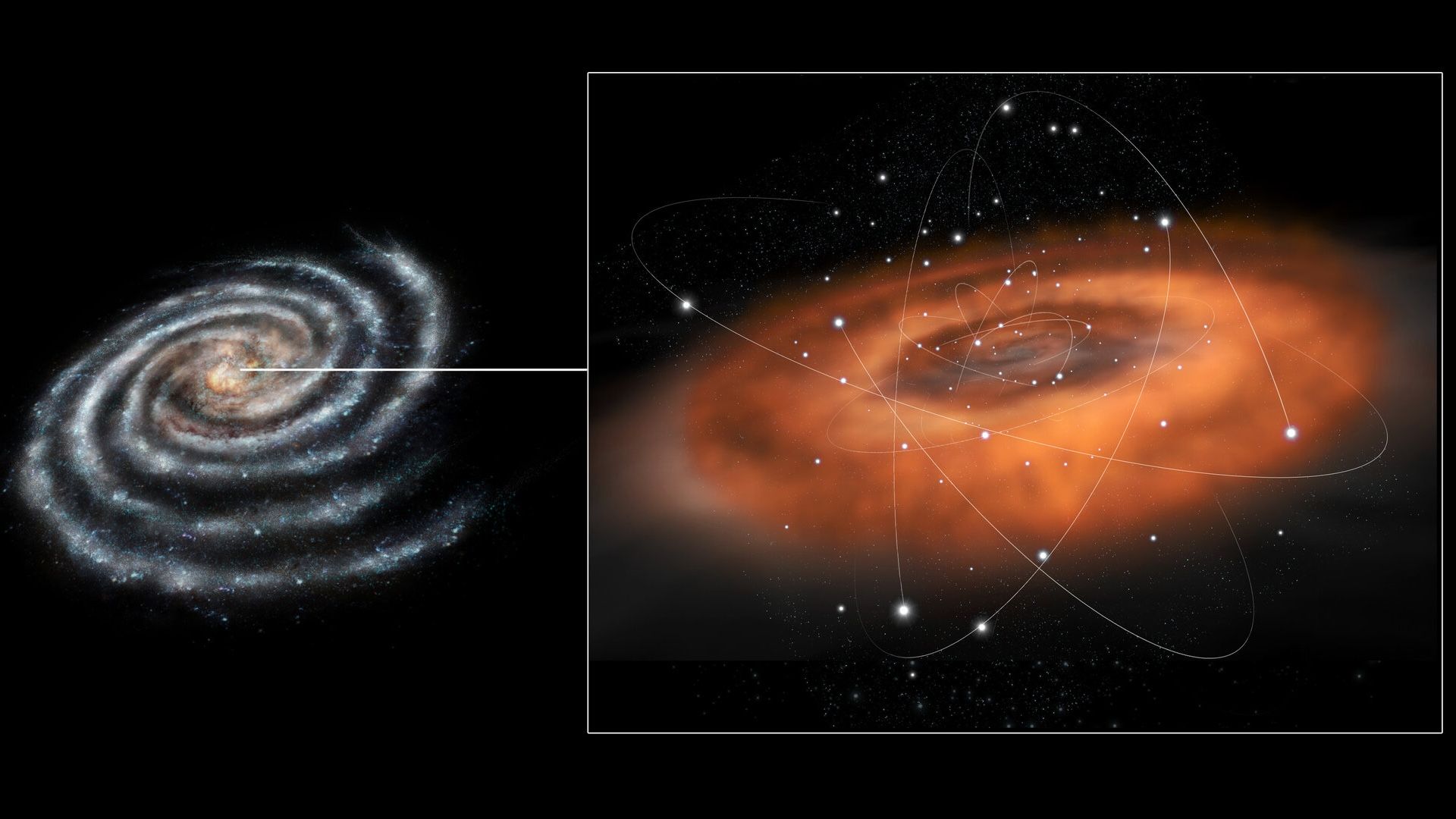

The Milky Way‘s galactic wave was spotted in mapping data from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia space telescope, which charted the positions and movement patterns of millions of stars with high accuracy before retiring earlier this year.

Astronomers still don’t know what started the motion. It could have been a past collision with a smaller, dwarf galaxy that caused the large shake, ESA officials said, but more investigation is required to answer that question.

The results were published July 14 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Mapping the wave

Gaia mapped the speeds and motions of stars for nearly a dozen years. In 2020, the telescope observed that the disk of the Milky Way wobbles like a spinning top. The newfound wave was charted by following the movements and positions of young, giant stars as well as a set of Cepheids — stars that have predictable-but-variable brightness.

“Because young giant stars and Cepheids move with the wave, the scientists think that gas in the disc might also be taking part in this large-scale ripple,” ESA officials wrote in the statement. “It is possible that young stars retain the memory of the wave information from the gas itself, from which they were born.”

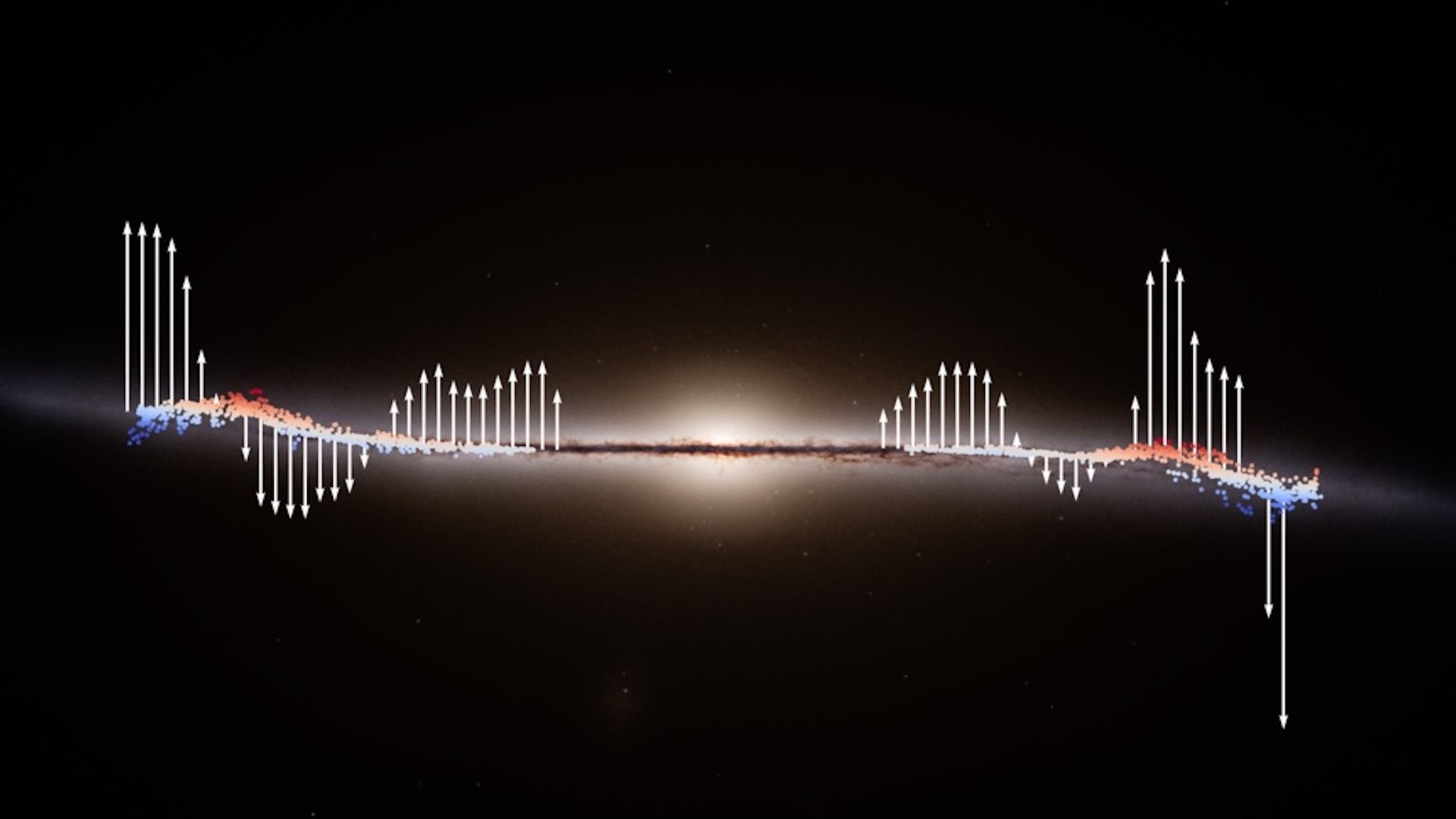

ESA officials likened the galactic wave to “the Wave” done by a crowd at a stadium: In a group movement starting from one side of the stadium and moving section by section to the other side, individuals rise from their seats, fully stand up with their arms extended, and then sit back down.

A similar type of wave motion is visible when our galaxy is observed edge-on. Such vertical motions, represented by arrows, show ripples of movement far across the Milky Way’s disk.

“This observed behaviour is consistent with what we would expect from a wave,” lead author Eloisa Poggio, an astronomer at the National Institute of Astrophysics in Italy, said in the statement.

The newly discovered wave could also be related to a much smaller Milky Way ripple already known by scientists. Called the Radcliffe Wave, it is visible about 500 light-years from the sun and stretches for 9,000 light-years across space.

“However, the Radcliffe Wave is a much smaller filament, and located in a different portion of the galaxy’s disc compared to the wave studied in our work,” Poggio said. “The two waves may or may not be related. That’s why we would like to do more research.”