Researchers have unearthed the oldest pterosaur ever discovered in North America and named it the “ash-winged dawn goddess.”

The 209 million-year-old pterosaur was among a cache of more than 1,000 Triassic fossils extracted from rocks in the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. Eotephradactylus mcintireae is partly named after volcanic ash found in the fossil bed and Eos, the Greek goddess of the dawn, because it evolved near the beginning, or dawn, of pterosaurs’ evolutionary history.

Pterosaurs, informally called “pterodactyls,” were flying reptiles that dominated the skies during the age of dinosaurs. The group produced many giants, some with wingspans stretching to around 36 feet (11 meters), but E. mcintireae and the other early members were tiny by comparison.

“This pterosaur would be the size of a small seagull, and could have sat on your shoulder,” study lead author Ben Kligman, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., told Live Science in an email.

E. mcintireae was just one member of a lost ecosystem described in the study, published Monday (July 7) in the journal PNAS. The cache of Arizona fossils also included giant amphibians, freshwater sharks, armored crocodile-like creatures and one of the oldest known turtle fossils.

These finds help researchers understand what animals were alive before the violent mass extinction event, likely triggered by volcanic eruptions, that brought the Triassic period to a close around 201 million years ago.

Related: Giant pterosaurs weren’t only good at flying, they could walk among dinosaurs too

Towards the end of the Triassic, northeastern Arizona was located just above the equator in the middle of the supercontinent Pangaea. At the time, the semi-arid landscape was marked with small rivers and channels that were likely prone to flooding, according to a statement released by the Smithsonian. Researchers suspect that a flood washed over the tiny pterosaur and other animals living in the region at the time, burying their bodies in sediment and ash.

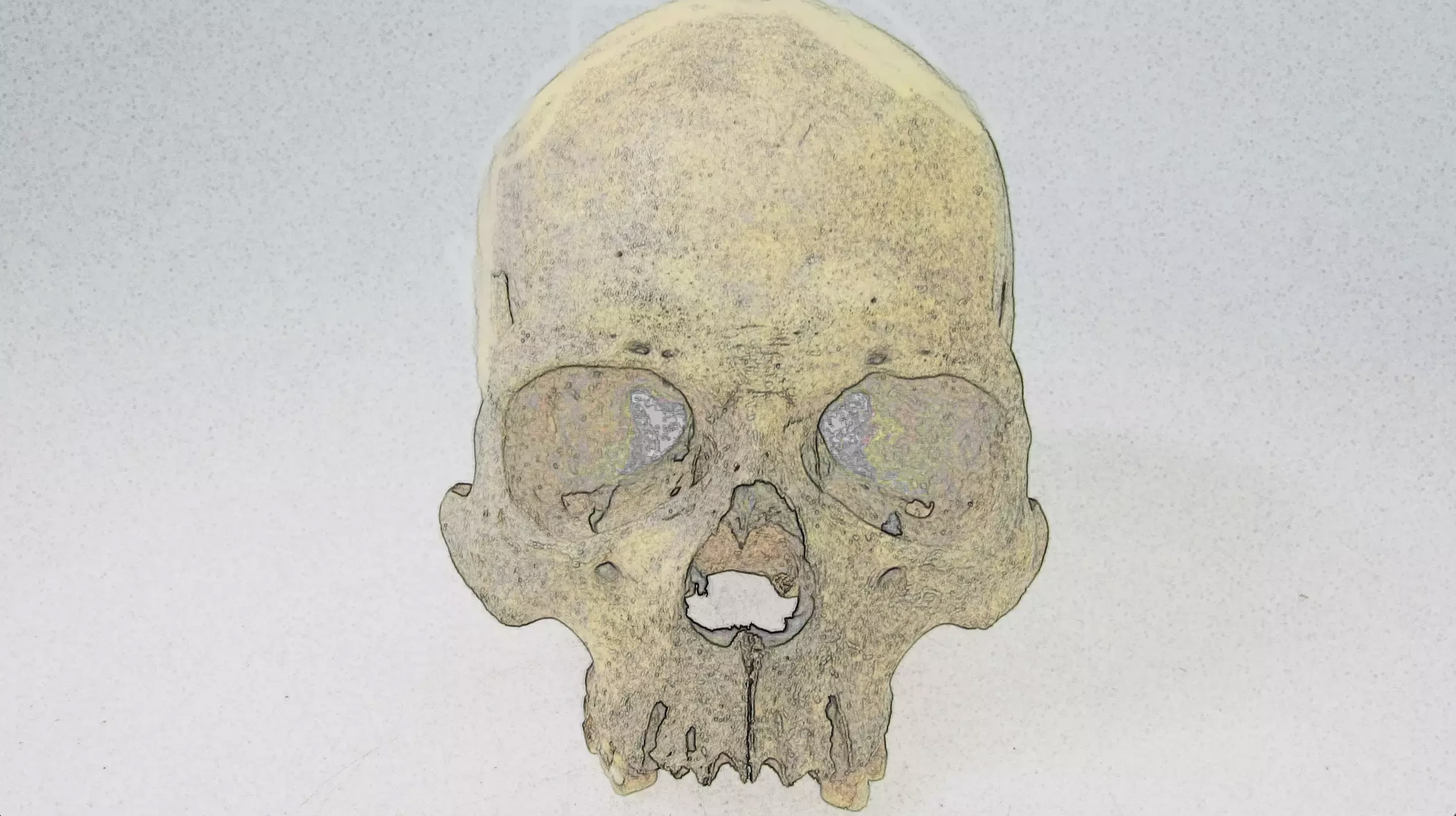

A team of scientists first discovered what remained of the Triassic bonebed in 2011. The fossils were mostly small and delicate, so rather than trying to excavate them in the field, the team extracted large chunks of sediment and worked through them in labs. Many chunks went to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, where volunteers spent thousands of hours carefully extracting the fossils. A volunteer named Suzanne McIntire extracted a jaw belonging to the pterosaur in 2013 — the species name mcintireae honors her discovery.

Kligman began working on the fossils in 2018, after the jaw had been discovered, and said he doubted the fossil was a pterosaur at first — at the time, researchers had only found one early pterosaur in North America, and none had ever been found in sediment deposited in a river.

“When I finally examined the jaw my doubts were put to rest — the distinctive teeth and jaw anatomy was unmistakably from a pterosaur,” Kligman said. “I was most surprised by the fact that a delicate, tiny jaw like this one had not been destroyed by the movement of river gravel prior to it being fossilized, suggesting that the bonebed was preserving a unique fossilization setting.”

The bonebed revealed a community of evolutionary newcomers, such as pterosaurs and turtles, sharing the landscape with each other and more ancient animals, such as giant amphibians, before the latter went extinct at the end of the Triassic.

“The presence of the pterosaur Eotephradactylus living and interacting in a community alongside groups like frogs, lizard relatives, and turtles is the first occurrence of this community type in the fossil record — these groups are commonly found living together in post-Triassic communities from the Jurassic and Cretaceous, however they had never been found together preceding the end-Triassic extinction event 201 million years ago,” Kligman said.