When the potentially hazardous asteroid 99942 Apophis makes its breathtakingly close flyby of Earth on April 13, 2029, more than 2 billion people across Africa and Western Europe will be able to watch it drift across the night sky. Under clear skies, the space rock will appear as a faint star — about as bright as the stars in the Big Dipper and easily visible to the unaided eye — gliding steadily overhead.

Apophis’ flyby will mark “the first time in space history that a potentially hazardous asteroid is visible to the naked eye,” Richard Binzel, a professor of planetary sciences at MIT, said Monday (Sept. 8) during a keynote address at the Europlanet Science Congress in Helsinki, Finland. Astronomers estimate that a close approach by an asteroid this large — 1,100 feet (340 meters) across, or roughly the height of the Eiffel Tower — occurs only once every 7,500 years.

For the public, it will be a dazzling, once-in-a-lifetime spectacle. For scientists, it promises something even rarer: a once-in-a-millennium natural experiment to watch in real time how Earth’s gravity reshapes a massive asteroid. “We don’t know,” Binzel said, “and we won’t know until we look.”

Binzel, a pioneer in asteroid hazard research and the inventor of the Torino Impact Hazard Scale that’s used to rate impact risks of asteroids and comets, underscored one point above all: “If you take nothing else away from this talk, I want you to take away three things,” he said during his presentation. “Apophis will safely pass the Earth; Apophis will safely pass the Earth; Apophis will safely pass the Earth.”

Related: NASA’s most wanted: The 5 most dangerous asteroids to Earth

When Apophis was first discovered in 2004, however, the picture was far less certain. Early calculations suggested a 2.7% chance of impact on April 13, 2029, placing it at Level 4 on the Torino scale — the highest rating ever given to a near-Earth object. Scientists named the asteroid 99942 Apophis, after the Egyptian god of the underworld, earning it the nickname the “god of chaos” asteroid.

Over the next two decades, continuous tracking and radar observations narrowed Apophis’ orbit from hundreds of miles of uncertainty to just a few. By 2021, Apophis was formally removed from all risk lists, and scientists estimated it posed no threat for at least the next 100 years. In September last year, however, a study noted there is still a tiny possibility that an unknown asteroid could nudge it onto a collision path before its close Earth flyby in 2029. The odds are over one in a billion, and while scientists won’t be able to fully rule out this scenario for another three years, astronomers remain confident Apophis poses no danger for the next century.

“It’s been a lot of work by a lot of people to make sure we can say totally and confidently that Apophis will safely pass the Earth — absolutely no doubt,” Binzel said.

“Earth won’t care, but Apophis will”

While Earth itself will barely notice the encounter, Apophis will not leave unchanged. As it passes just over 18,600 miles (30,000 kilometers) above the planet’s surface — closer than geostationary satellites — its Aten-class orbit, which lies mostly inside Earth’s path around the sun and is thus often hidden in our star’s bright glare, will be reshaped into a wider Apollo-class trajectory. Its rotation may also shift, which might send the asteroid into a fresh tumbling state, Binzel said.

“The Earth won’t care, but Apophis will care, because Apophis’ orbit will change,” he said. “It’s all about the encounter physics.”

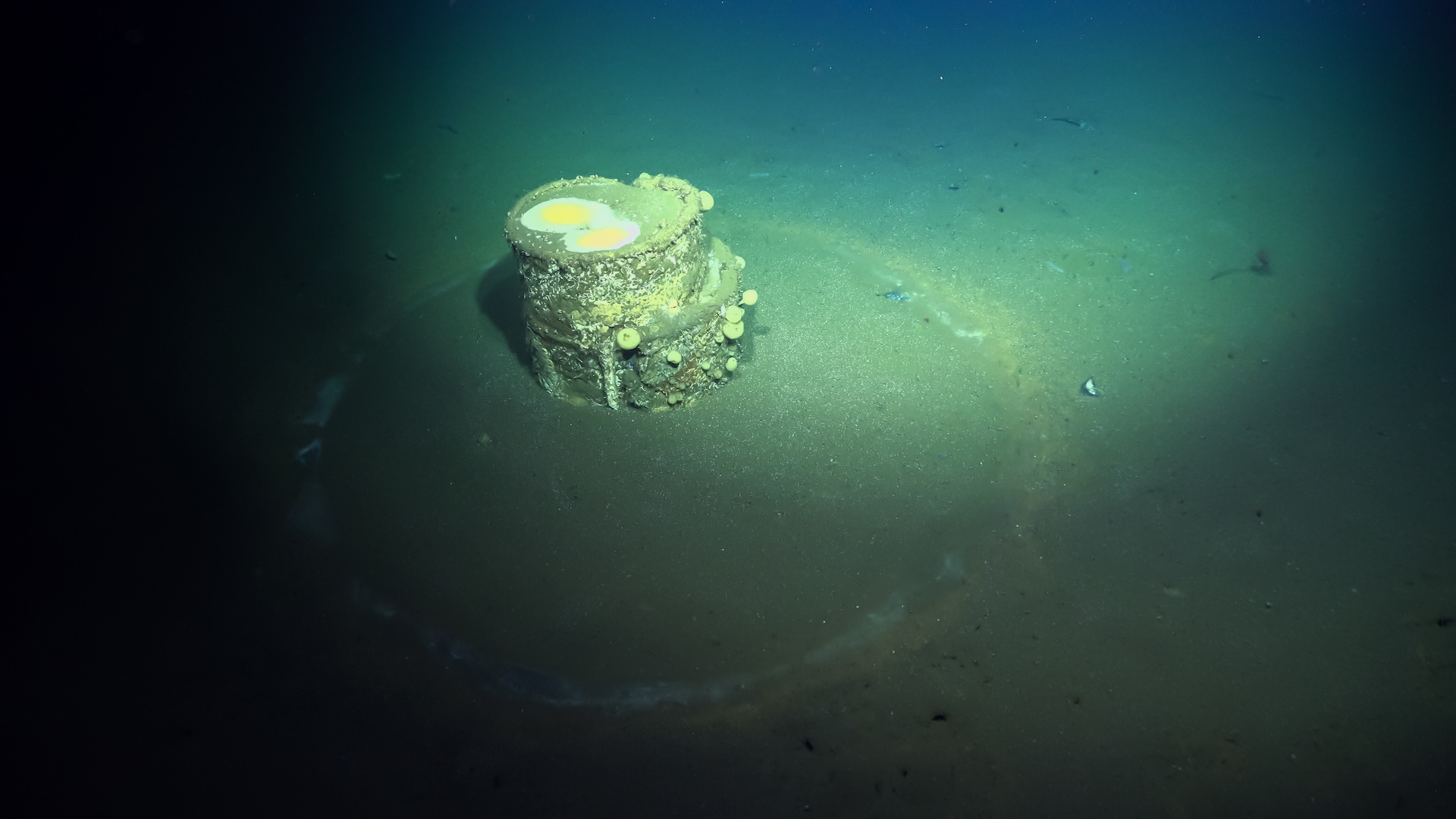

To capture those changes firsthand, NASA has reassigned its OSIRIS-REx spacecraft, fresh from its mission to the asteroid Bennu, to a new role as OSIRIS-APEX. The probe will rendezvous with Apophis before the flyby, mapping its surface, monitoring its spin, and measuring how Earth’s gravity alters the asteroid during its close pass. Among the most tantalizing goals, Binzel said, is the chance to measure seismic vibrations inside Apophis.

“In 60 years of planetary science, we’ve only measured seismicity for two objects: the moon and Mars,” he said. “This would be the opportunity for another leap forward in seismic measurements and interpretation of interior properties.”

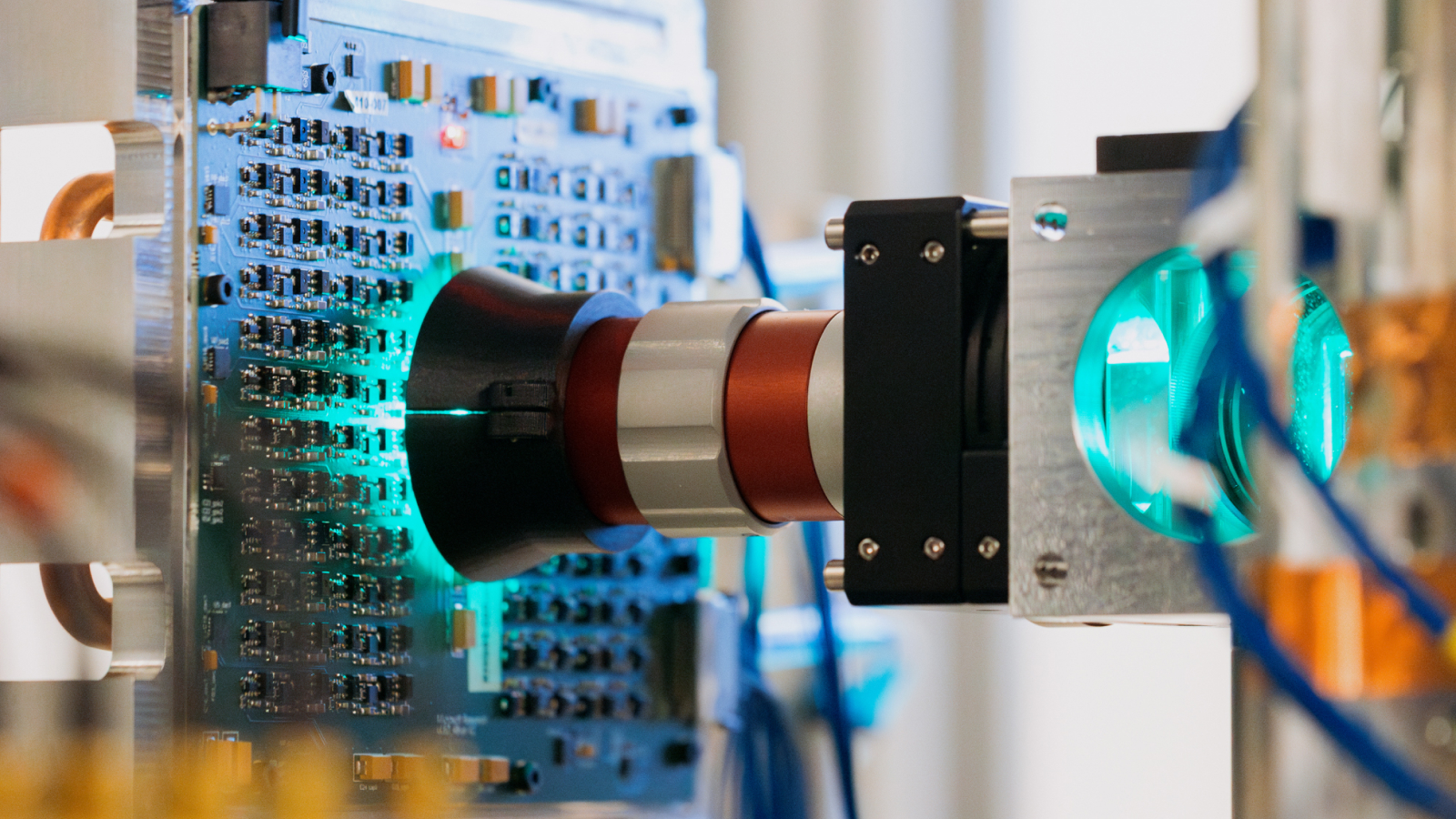

That leap could come from the Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety (RAMSES). The European Space Agency (ESA) mission, if approved at ESA’s Ministerial Council in November, would launch in spring 2028 and arrive at the asteroid by February 2029. The mission’s goal would be to observe Apophis before, during and after its flyby of Earth, Monica Lazzarin, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Padua in Italy and a member of the RAMSES science team, said at the conference.

Hovering as close as 3 miles (5 km) from the asteroid during its April 12-14, 2029, encounter, RAMSES would map Apophis’ orbit, search for dust clouds raised by tidal forces, and possibly deploy a small satellite called a cubesat to touch the surface and detect seismic waves, Lazzarin said.

Beyond science, Apophis is a proving ground for planetary defense, scientists say, as it will aid humanity’s effort to understand and prepare for the rare-but-real risk of an asteroid impact. While Apophis itself poses no danger, it belongs to the class of near-Earth asteroids that could one day threaten our planet. By studying how Earth’s tidal forces reshape Apophis, scientists can refine the models that would be critical for deflecting a hazardous asteroid.

“Apophis is not a planetary defense emergency,” Tom Statler, a planetary scientist at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., added during a Q&A session at the conference. “It is an opportunity, and an unprecedented one.”

“Asteroids are not something to be scared of,” he added. “They’re something to understand — and that’s what we’re doing.”