A volcano in southern Iran thought to have been extinct for some 710,000 years has stirred.

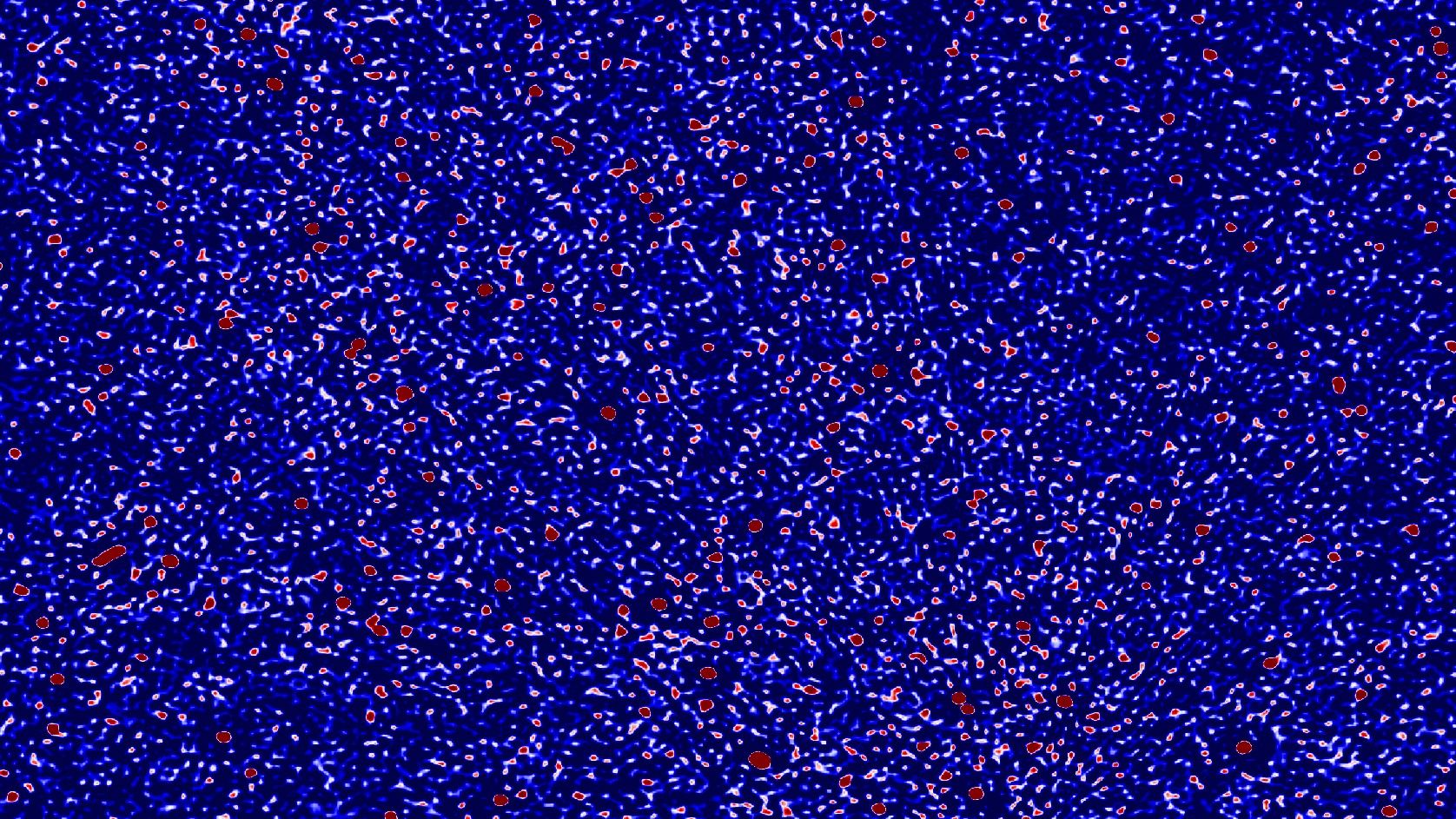

New research published Oct. 7 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters finds that an area of ground near the Taftan volcano’s summit rose 3.5 inches (9 centimeters) over 10 months between July 2023 and May 2024. The uplift has not yet receded, suggesting a buildup of gas pressure below the volcano’s surface.

The findings reveal the need for closer monitoring of the volcano, which hasn’t been considered a risk to people before, said study senior author Pablo González, a volcanologist at the Institute of Natural Products and Agrobiology, a research center of the Spanish National Research Council (IPNA-CSIC). Volcanoes are considered extinct if they haven’t erupted in the Holocone era, which started 11,700 years ago. Given its recent activity, González said, Taftan might be more accurately described as dormant.

“It has to release somehow in the future, either violently or more quietly,” González told Live Science. There is no reason to fear an imminent eruption, he said, but the volcano should be more closely monitored.

Taftan volcano is a 12,927-foot (3,940 meters) stratovolcano in southeastern Iran, situated among a rumple of mountains and volcanoes that was formed by the subduction of the Arabian ocean crust under the Eurasian continent. Today, the volcano hosts an active hydrothermal system and smelly, sulfur-emitting vents called fumaroles, but it isn’t known to have erupted in human history.

When Mohammadhossein Mohammadnia, a doctoral student working under González at IPNA-CSIC, first examined satellite imagery of the volcano in 2020, he saw no evidence that it was doing much of anything. But then, in 2023, people started reporting gaseous emissions from the volcano on social media. The emissions could be smelled from the city of Khash about 31 miles (50 kilometers) away.

Mohammadnia took another look at the satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-1 mission, which provides round-the-clock imagery of Earth’s surface. Taftan is remote and does not have a GPS monitoring system such as those found on volcanoes like Mount St. Helen’s; the area is also dangerous due to the activity of insurgent groups and border conflicts between Iran and Pakistan. The satellite imagery revealed a slight rise of the ground near the summit, indicating increased pressure below.

Mohammadnia calculated that the driver of this uplift sits 1,608 to 2,067 feet (490 to 630 m) below the surface. It’s impossible to know exactly what is going on, but the researchers ruled out external factors like nearby earthquakes or rainfall, Mohammadnia told Live Science. The volcano’s magma reservoir sits more than 2 miles (3.5 km) down — far deeper than whatever is driving the uplift.

Instead, either the uplift is caused by a change in the hydrothermal plumbing below the volcano that is leading to the buildup of gas, or a small amount of magma may have shifted beneath the volcano, allowing gases to bubble up into the rocks above, raising the pressure in rock pores and fractures, and causing the ground to heave up slightly.

The next stage in the research, according to González, will be to collaborate with scientists who do gas monitoring at volcanoes.

“This study doesn’t aim to produce panic in the people,” he said. “It’s a wake-up call to the authorities in the region in Iran to designate some resources to look at this.”