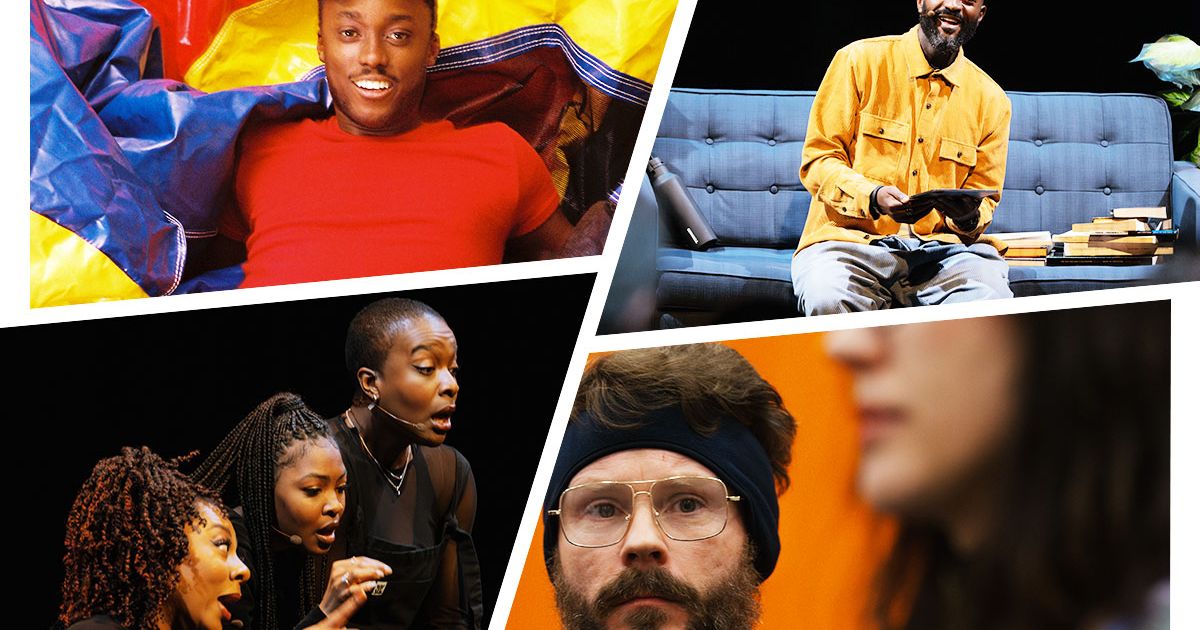

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Maria Baranova, Bjorn Bolinder, Courtesy of You Are Who You Eat, Courtesy of The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu

Editor’s note: Last week, I started a festival diary to chronicle my magical mystery tour through January’s abundance of new and experimental theater. Now it’s time for Week Two.

It’s Monday, and it’s time for puppets. The show I’m on my way to tonight isn’t actually a part of any of the January festivals, but it feels kindred to the fest spirit. It’s Ernie’s Secret Life at Dixon Place, created by Concrete Temple Theatre, the brainchild of co–artistic directors Renee Philippi (who wrote and directed the show) and Carlo Adinolfi (its puppetry and set designer and its main performer). Concrete Temple has been putting up shows at Dixon Place for more than 20 years, and tonight’s performance will be followed by a sweet Champagne toast to the company’s creativity and longevity and to the venue’s unflagging support of NYC puppet theater. Cheryl and Heather Henson are even there to raise the first glasses, although this Ernie is unrelated to their dad’s.

Ernie tells the story of its soft-spoken, big-dreaming protagonist, played by Adinolfi — a man who’s worried he’s wasted too much time with his head in various clouds. His son, Daniel, he informs us with a mixture of pride and anxiety, is “in Nova Scotia,” and Ernie has convinced himself that the boy needs rescuing. (What else is a postcard that says “Wish you were here?” supposed to mean?) And so, inspired by another Ernie — his hero, Shackleton — this one has built a sweet, spindly looking green canoe and decided to set out on a quest to save Danny from … well, Canada, presumably.

Carlo Adinolfi in Ernie’s Secret Life.

Photo: Stefan Hagen

Adinolfi’s scrappy, ingeniously engineered puppets, built mostly of cardboard, are the great delight here. Ernie’s odyssey is a bumpy one — delayed and sidetracked by, among other things, his deathly fear of water — and when the world drops him into potholes, he escapes into his imagination. A fantastical underwater sequence in which he envisions himself as a big orange fish, fending off an evil undersea lurker with spiky teeth and red flashlights for eyes, is totally charming (not to mention nostalgic). I couldn’t look away from a beautiful fox puppet, rendered in foreshortened form and gracefully manipulated by Tau Bennett, one of the show’s six supporting puppeteers. And a flock of seagulls is wonderful for the evocative simplicity of the birds’ construction (the little wire that makes each one able to turn its head is the kind of tiny, extra-thoughtful touch that appears throughout the show). There’s also great play with scale: Various puppet versions of Shackleton, from the tiny to the enormous, pop up to encourage Ernie along the way, and a wooden figure rowing its own little boat appears tiny at a distance, then rows into view at full size. It’s all just paper and cardboard, paint and wire, tie line and plastic sheeting — and in the hands of Concrete Temple, all those things have their own enchanting secret life.

I’ve managed to fit every show in UTR’s main program into my calendar — but I have to admit that I’ve only been able to include one of the festival’s UFO shows (and only because they’re letting me come to a dress rehearsal). UFO is — to use the fest’s own language — its “work-in-progress series of staged readings and scaled-down productions.” (Why UFO? Something to do with how these shows are rare, fringy “sightings”? It’s not entirely clear.) Today I’m seeing Bag of Worms, a work in progress by the multimedia artist Matt Romein. This is another of those “… There’s an experimental theater here?” situations: I’m walking past the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree, Christie’s, Michael Kors, Armani Exchange … into a huge posh lobby shared with the Onassis Foundation. The ONX Studio, a security guard tells me, is in the basement.

As basements go, it’s swanky — a black box, but really clean. Romein starts the show sitting center stage at a mic and greeting us genially. He’s tall and self-possessed with a deep voice and a broad, warm smile — both of which hover in a fascinating place between being genuinely welcoming and vaguely unsettling. Is he giving big brother or Big Brother?

Romein often works with Peter and Julia (see last week’s diary entry!), and you can sense a simpatico aesthetic — the direct address, the technological meditation, the performance of a self that’s part mask or a mask that’s part self. Here, Julia is working with him as director and Peter as sound designer. In Bag of Worms’s earliest iterations, they were also onstage as Romein’s fellow performers. Now, those roles are filled by Tim Platt (all jittery, try-hard enthusiasm) and Amy Zimmer (silent and deadly).

Bag of Worms.

Photo: Ann Marie Dorr

Before the show is over, we’re going to see Amy kill Tim in, as Shakespeare once put it, “a hundred and fifty ways.” They’re both in mo-cap suits, and Romein — who is, among other things, a video-game fanatic and a serious coder — has created a roulette wheel of digital scenarios for them to play out, their Sims-like avatars projected in real time on a screen at the back of the stage. He’s interested, he tells us, in “empathy for the digital body.” Why? Well, it all started with a very deep Reddit thread about the Mario character Toad. The subject of ferocious, multi-post debate: Is the mushroom cap his hat … or his head?

Listening to Romein wax existential (and emotional) over this kind of question is quite funny — as is watching digital Zimmer decapitate digital Platt with a digital chainsaw. And then it’s also something other than funny. As with Romein’s smile, it’s unnerving, too — even strangely melancholy. What do we get out of spending hours and hours in spaces where it’s easy, even fun, to riddle other bodies with bullets or behead them or stab them in the back or lock them in a room and let them starve (as an audience member, when questioned, admits she used to do with her Sims), because they’re just collections of pixels? What is the thrill — and, ultimately, the effect on the soul — of spending so much time outside the viscera of our physical selves?

After ascending from NYC’s least rat-infested black box, I’m on my way back down to Fidi for another PhysFest show. Unbeknownst to me, there’s some overlap between the first one I saw, War & Play, and this one: The Crone Chronicles. It’s a company-devised piece produced by Yeda יֶדַע Theatre (the Hebrew in their name means “to know”), and Danielle Levsky, one of War & Play’s creators, is also at the heart of things here.

The Crone Chronicles.

Photo: Bjorn Bolinder

This time, she greets us individually as we enter the theater — the combination of age lines, garish blue eyeshadow, slippers, cozy sweater, and kerchief all say only one thing. This is Baba Yana, the “Soviet Jewish Grandma Clown.” She’ll be our narrator as we listen to the story of Chava, a young girl whose unsympathetic (and also goyish) stepmother sends her into the deep dark woods to fetch fire from (scary sound cue) Baba Yaga.

I love Slavic folktales, and I’m theoretically into the idea of a feminist reclamation of the legend of Baba Yaga, which is the play’s real goal. Did you know that the “child-eating” part of her myth comes from a smear campaign by the frightened patriarchy against women herbalists who performed abortions? (Same goes for the witch in “Hansel and Gretel.”) I didn’t, and that’s genuinely interesting. The show overall, though, is too repetitive and cutesy for me. It hasn’t quite figured out how to have certain things happen three times (necessary for fairy tales) without creating theatrical sag. It’s also got the feeling of a performance made for children, but there aren’t any in the room, and even if there were, I tend to be suspicious of addressing anyone as if they’re little kids, especially little kids.

Tonight I’m back in the land of designer storefronts as I head east from the 51st Avenue 6 stop, seeking out the Japan Society. The show is HAMLET | TOILET, and yeah, as titles go, this one pretty much sums it up. The Japanese playwright-director Yu Marai and his company, Kaimaku Pennant Race, have created risqué riffs on Shakespeare before, including a mash-up of Rocky and Macbeth and a previous visit to the water closet with Romeo and Toilet. If your primary complaint about Hamlet has always been that there’s not nearly enough poop in it, then HAMLET | TOILET is here to help you fart-dels bear.

For 90 minutes (which is, I gotta say, too many minutes), three extremely game, white-bodysuit-clad actors sketch out the basic contours of Hamlet, skewing things scatalogical wherever they can be made to skew. We meet Hamlet, played by Takuro Takasaki, straining and grunting on the toilet (embodied by the other two actors, G. K. Masayuki and Yuki Matsuo). The prince is constipated — spiritually and otherwise. He won’t be able to “cleanly and completely defecate” until his father is avenged. Dad died, by the way, because Uncle Claudius shoved poison up the royal posterior while the king was trying to relieve himself in the bushes. Ophelia has an enormous wig (hat?) made of toilet-paper rolls and her drowning is accompanied by flushing effects. The final fencing match is fought with plungers.

Hamlet|Toilet.

Photo: Maria Baranova,

You get the idea. I wish I found the whole thing funnier, because it is supposed to be funny. It’s not that Marai and his actors are taking themselves too seriously (sometimes they even genuinely crack up). It’s that I’m not sure the show succeeds in doing much other than prompting a low tide of self-conscious giggling. Each of its various physical bits runs on for minutes past its sell-by date (think Peter Griffin versus the chicken with less escalation), and the few instances of gesturing to a through-line that isn’t just poop jokes — one that has to do with isolation, regret, bodily breakdown, and fear — don’t really accumulate or stick.

There’s a part of me, though, that wonders what cultural fluency I lack here. Japan is, to put it mildly, really interested in poop. It helps teach kids to read and it has its own museum. I’m still getting over the fact that, even to bring HAMLET | TOILET to UTR, the artistic director of the Japan Society essentially had to argue to a consular official that the second part of the title is more important than the first. (Toilets, she notes in the show’s program, are “representatives of the uniqueness of contemporary Japanese culture.”) So perhaps I’m not vibrating on all the same frequencies as Kaimaku Pennant Race, but that’s okay. As I left the theater, I heard a dazed young man saying to his date, “That was … the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen.” And that’s never a bad thing.

Tonight’s show features the unique challenge of taking notes with my hands tied together. This is The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu, created by the South African performance artist Albert Ibokwe Khoza. The piece blends ceremony, exorcism, memoir, mourning, video, and dance, and as we enter the theater, each of us is asked for our consent to have our wrists bound with a piece of thick twine. Khoza stands center stage, statuesque and imposing in a massive black ball-gown skirt and a black hat that sits balanced atop their coiled braids. Their fingernails are silver talons. In one hand, they swing an object like a censer. In the other, they hold something I can’t quite identify — a plate or a dish; maybe it contains grasses or grains of some kind? What’s true at the beginning is true throughout the show: This is clearly and emphatically a ritual, though its various rites aren’t explicitly defined.

The Black Circus honors the millions of African lives destroyed and displaced by colonialism, imperialism, and the slave trade, focusing specifically on the sickening 19th and early 20th-century fad for “ethnological exhibitions.” These were, essentially, freak shows: touring human zoos that put Black and brown bodies, like those of Mbye Otabenga and Saartjie Baartman, on display for titillated white audiences. As part of their tribute to the dehumanized — the imprisoned, lost, and enslaved — Khoza puts their own body on the line. They play both ringmaster and exhibit, laughing menacingly into a megaphone as they announce the spectacle of “the manly woman” — then stripping nearly naked and parading through the space. (Khoza themself identifies as “a non-binary womanly man,” so there’s a sharp pointedness to this ancestral anguish.) They also dress two white audience members in gorilla masks before cracking a whip and ordering them to dance to blaring circus music.

The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu.

Photo: Maria Baranova

It’s a lot … But then, at the same time, somehow it isn’t. After releasing the two audience members, Khoza, shivering and sweating, spends a moment quietly crying near the back of the stage. They flick their hands violently as if shaking off dirty water. They dry their face, take a deep breath, and continue. What they are experiencing — physically, spiritually — is clearly immense, overwhelming. But I’m not so sure the same can be said for most of the audience. There’s a difference in temperature between Khoza’s ritual — their own bodily observation of it — and the audience’s knowing intellectual engagement. One burns, while the other stays cool.

In a way, we’re too informed: We know the rules of experimental-theater participation, which include being asked to do apparently intense things like being tied up or forced to dance. And while we might be game (and I think people are), we’re also being held in a mostly static place of dutiful mortification. We can reflect on our own complicity, ancestral and present, and we can consider our relationship to or even our enactment of what Khoza calls “the imperialist gaze” — a violent, complacent form of spectatorship that they’re trying to smash through. But we could also do these things while reading a good essay or listening to a smart podcast. I gasped audibly in a coffee shop while reading about the life of Mbye Otabenga — something I never did during The Black Circus.

At the beginning of the show, Khoza sprinkles a circle around themself using salt and dirt. Then they offer a pinch of either to every audience member. I held a little handful of salt throughout the whole show — and never did anything with it. At the end, I sought out the cup my salt had come from and put it back, so it wouldn’t go to waste. There’s a version of The Black Circus in which that salt in my hand is given real weight and attention — in which we are fully called to participate in Khoza’s ritual, rather than partially. There’s a version where the communal heat rises, where every single body in the space experiences ecstasy, torment, rage, grief, and perhaps even a kind of catharsis — holds these things together, which is different than witnessing or contemplating them.

I’ve got a three-show day today, starting in Brooklyn. The Invisible Dog Art Center is a big, open, warehouse-style space off Smith Street, where a single chandelier currently dimly illuminates two large walls of numbered lockers. Tania El Khoury’s Cultural Exchange Rate is as much installation as it is performance art — the artist’s body isn’t part of the project, though her voice and presence are. As we receive instructions from our audience guides, it feels like we’re being prepped for an escape room.

We each get a big jangly set of keys (very satisfying). We’ll all end up opening the same ten lockers, but in staggered order, so that each audience member gets an individual variation on the same experience. I approach my first locker, open it, and — as instructed — stick my head inside the black cloth that is stretched across the opening, a slit in its middle. I feel like a giant — which is to say, a child — peering into a doll’s house. Inside every locker is a carefully constructed diorama, all with either a video or audio component. Our faces are right up against artifacts from El Khoury’s life — a pile of coins, a collection of immigration cards, a lock of her grandmother’s hair. And her voice is in our ears (in Lebanese, in Spanish, and in English), piecing together a story of her heritage, of her family’s many migrations, and of a trunkful of devalued Lebanese currency collected over time by her grandfather and her father. Lebanon is in the midst of a prolonged economic crisis, its exchange rate down to 15,000 Lebanese lira to the U.S. dollar.

Cultural Exchange Rate.

Photo: Argenis Apolinario.

El Khoury is ruminating on how we assign worth and on how relative wealth isn’t just a matter of possessions but of freedom of movement — the poorer you are, the more borders are closed to you. (For many Lebanese, she says, “visas, residencies, and other citizenships are the ultimate treasure.”) We are the artist’s avatars, guided by her invisible hand to sift through pieces of her inheritance — literal and otherwise — and the experience is like going through a stranger’s attic or like finding an old postcard in the back of a used book: meditative, a little mysterious, a tiny window into a branching fractal of other lives.

After a couple of hours in a coffee shop trying to warm up, I’m on the R to NYU Skirball for the windily titled William Shakespeare’s As You Like It, A Radical Retelling by Cliff Cardinal. Skirball is the kind of venue with a subscriber base. We’re not in a musty basement with possibly sub-code wiring and Coors Lights in a cooler. There are a whole lot of older white people in this room. This will matter for the show.

Now: a huge spoiler alert. As You Like It is wrapped up at UTR, but if you think you may want to see Cardinal’s ultrawily spin on Shakespeare’s pastoral crowd-pleaser in the future, don’t click the text below. Secrets lie ahead.

So there’s a theory — possibly apocryphal — that Shakespeare was feeling cynical when he titled his 1599 comedy. One could argue that he wasn’t in an especially breezy mood — Julius Caesar and then Hamlet were on the horizon, and Twelfth Night, the last and greatest and by far the most melancholy of the pure comedies, would follow. After that, the laughter in his plays would only become more shadowed and bitter. For those who don’t think much of As You Like It, it’s not a stretch to argue that Shakespeare was doing one for the studio: packing a play full of all the easy popular tropes — romance, cross-dressing, rustic revelry, miraculous conversions, divine interventions, weddings, weddings, weddings — and tying it all up with a neat, snarky little bow. “Here you go, kids, have it as you like it.”

And this is where Cliff Cardinal comes in. Cardinal wants us destabilized, alienated, thrown for a loop: He wants us asking ourselves what we expected when we walked into the theater and reckoning with our own reactions when we fail to get it. Cardinal — a Toronto-based writer and actor who is Lakota-Cree-Dene and who was born on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota — is about ten minutes into the land acknowledgement he’s entered to deliver before the play … when we realize that there’s not going to be any play.

Cardinal’s show is a grand, gutsy bait and switch: Reel them in with the big daddy of famous white playwrights; keep them on the hook for a 90-minute-long “land acknowledgement.” Well, not really a land acknowledgement — as Cardinal tells us almost immediately, he loathes land acknowledgements (a truth that’s also calculated to add an extra barb to the hook for certain audience members: “See, Mildred? I’ve been saying all along these things are crap!”). What we’re really in for is an hour and a half of something like stand-up — very raw, very serious stand-up with a big, laid-back, fuck-you smile. Cardinal’s face quicksilvers between friendly, “I mean, what can ya do?” absolution and icy, bitter judgment, and the former is always a trap.

It’s a feat in our era of exhausted savviness to get adrenaline really pumping through a theater, and Cardinal manages it. I haven’t been at a show with genuine hecklers in a long time, and at As You Like It, some gasp-worthy shit went down. As Cardinal was making a dig at wealthy Upper East Siders, a woman’s voice sounded coldly from the middle of the audience: “If you had the money you could rent an apartment!” Cardinal choked on a laugh but didn’t miss the beat: “Spoken like a true rich bitch,” he said. Later, he got into an extended argument with another woman in the third row who wouldn’t get off her phone. “Are we still doing this?” he said after fully shaming her once with, apparently, no result. “Put your fucking phone away.”

“I’m angry,” Cardinal tells us late in the show. We know it, but he hasn’t said it yet. What he’s been doing for 80 minutes is acknowledging — pointing to crimes still unaccounted for and wounds still unhealed and perhaps unhealable. “At what point are we finished acknowledging the abduction and murder of over 7,000 schoolchildren?” he asks. “I’m angry and I’ve tried to keep my anger out of the room, because I’m in show business and show business is about being liked.”

Courting “likes” — keeping everything as you like it — is, Cardinal is arguing, its own kind of lie, its own form of violence. It piles dirt on the unmarked grave; it puts a pretty bow on the festering wound. “I lied to you and took your money,” he says with a huge grin once the whole audience has realized that Shakespeare’s not on the menu. “Now you know what it feels like to be Native.”

It’s the big punch line of the evening, though I’m not sure it isn’t mid-to-low-hanging fruit. Cardinal’s gambit is a slippery one — for me, though I dig its sheer moxie, his show slid continually back and forth between fiery but open and cold and closed. I found myself thinking of Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette, another act of half-stand-up, half retributive justice, which I watched with a feeling of melancholy distance (and more than a little disappointment). Anger and shame are sharp weapons, but they don’t create much breathing space. They tend to leave artists teetering between militancy — because of the aspect of their identity that has been grievously wronged, that needs redress — and a niggling desire for complexity, for ambivalence and curiosity — because of their identity as artists. This leads to shows that are stuck — highly charged and often lauded as “powerful” but hobbled by their own rigidity. Hard lines and righteous orthodoxy are seductive in a world so full of horrors, but their pull is its own snare, tightening the more we kick, pulling us away from the softer, scarier place, the place where we are less certain, bigger-hearted, and more free.

The day’s not over yet. But don’t worry — this entry almost is! Last on the docket today is my final PhysFest outing, a late-night showing of Fly, You Fools! by the comedy troupe Recent Cutbacks. The premise is simple: It’s three actors and a foley artist, with a handful of cheap props, reenacting Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring.

The thing is I’m feeling a little too seen. When Fellowship came out, it blew my teenage brain out the back of my head. I’m not actually going to tell you how many times I paid to see it. But I will tell you that between 2001 and 2003, my sister and I attempted to film our own shot-for-shot remake of Fellowship, just the two of us (and sometimes our family’s cats), on the chunky analogue video camera my grandfather had given me. You couldn’t edit on this thing. Everything had to be shot in order. We only ever made it to the Mines of Moria. Our epic remains unfinished, though it was committed to DVD by my father. Basically, we inspired Be Kind Rewind.

Everything except that last sentence is true. Anyway, I kind of can’t believe my secret teenage magnum opus is live on stage, and the show is a total riot. I lose my voice laughing at it. The foley work is particularly wonderful — Blair Busbee does a great Cate Blanchett impression while swirling her fingers in a 28 ounce tomato can full of water underneath a microphone (she feels it in the water, you guys). There’s a solid-gold moment involving plastic wrap and the birth of Lurtz, and there’s also some fantastic play with zoom and scale: An actor mime-galloping on an invisible horse suddenly is replaced by that actor’s hand, cantering like a little animal at a long distance as the other actors frame the shot with their own digits.

It’s lovely to end the night with such brazen, joyful silliness. Recent Cutbacks are performing the show two more times this weekend at BK Art Haus, so if you, like me, still cry over Sean Bean dying in Viggo Mortensen’s arms, then I guess you know what you’re doing Saturday night. Namárië.

I took Saturday off (gasp!), it feels like this outside today, and it’s time to finish Week Two with a “gender cannibalism” cabaret and a mercurial, processional movement theater piece tucked away in a Bushwick warehouse.

First up is Rose: You Are What You Eat, created by the Philadelphia artist John Jarboe with her company, the Bearded Ladies Cabaret. The setup is one of those quaint little family stories that’s both true and truly wild: When Jarboe was 33 — already decades into grappling with her gender identity in the wake of a Michigan upbringing she describes as an unholy “casserole” of hockey, hunting, Tupperware, and Republicanism — her Aunt Margot told her that she’d had a twin in the womb. “But you ate her,” said helpful Aunty M. “That’s why you are the way you are.”

That’s — as Jarboe deadpans — “a lot to digest.” Her melodic, bespangled, generous show is a way of doing just that. (It also honors burlesque’s shameless affinity for puns, throwing in plenty of cannibal-happy wordplay along the way.) Anyone who’s worried about grisly content can relax their shoulders: Jarboe isn’t all that interested in body horror. She’s a warm, playful hostess — “Sasha Velour meets Mighty Ducks,” she tells us, sporting a ruched, zip-front mermaid gown brilliantly assembled out of a hockey jersey. (Rebecca Kanach did the costumes and Christopher Ash designed the set and video, all of which ingeniously blend Jarboe’s roots and her current flowering form: We get duck-blind camo netting and gilly suits, all lavishly adorned with roses.)

Rose: You Are Who You Eat.

Photo: Steven Pisano

Jarboe treats the consumption of her fetal twin — called “Rose,” because that’s what Jarboe’s mother would have called her, if she’d been “born different” — as a murder to be investigated. She leads us through various “exhibits”: a childhood photo album, a string of pearls, a tube of lipstick. In one of the most vulnerable, bittersweet sections of her show, she reenacts a performance that “little John” gave for “Mother and Father”: Wearing only underwear and long socks flapping from her hands, she cavorts around the space, wiggling ecstatically, sharing her grand “experiment in freedom.” It’s a perfect invocation: Who didn’t do a version of this dance as a kid? Yet this was the moment, Jarboe recalls, when she watched her parents’ faces change — loving, proud, supportive affirmation replaced with anxiety, fear, judgment. “When did dress-up become bad?” she asks. The engine of Rose: You Are What You Eat is ultimately love — hard-won and still-evolving love of self that could only be arrived at by loving someone else first, another “I” transformed into a “You” so that it could both receive and give the vital assurance of worthiness and beauty.

A similarly tender, glowing heart is present at the center of Those Moveable Pieces, though we go on an enigmatic progress to uncover it. Created and performed by Nicholás Noreña and Timothy Scott of the experimental theater company the Million Underscores, Those Moveable Pieces is the first show I’m seeing in this year’s Exponential Festival. Out in the low-slung, hip-AF, geographically askew part of Bushwick, we’re at a warehouse venue called We Are Here. The show begins with the audience packed around the periphery of a small room, bright blue walls and pink carpet, red candles in candelabras, a breeze blowing surreally from behind a long white curtain (aren’t we far from any real windows?). Noreña lies splayed on the rug, trouserless, wearing sock garters, his mouth pressed up against a microphone. Scott wears a cravat and circumnavigates the space coolly. Voices hum from an old tape deck; the candles flicker. Is Scott some kind of psychiatrist or detective? Are we piecing together Noreña’s broken memories?

The show will elicit many more questions than it answers — soon enough, I adjust my lens and begin to take it in as a series of impressions, strange and intimate, evocative and gestural. As the audience follows Scott to another room — this one papered with garish palm fronds — I start thinking of Rainer Werner Fassbender, especially The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant. There’s something here that mimics the way Fassbender’s sets feel like artificial boxes, frames within frames where the walls are only flats — and something similar in the currents of queer attraction, the prickling, stifled sexual charge of bourgeois spaces filled with houseplants and fluffy rugs and heavy furniture.

Noreña and Scott are dancing together even before the show evolves into a more explicitly choreographed physical duet. When we follow them into a third space (where, rewardingly, we get to see the backs of the other two rooms’ flimsy walls, and the fan blowing air through that original mysterious curtain), they twirl and squat and kick to a Jane Fonda workout routine. They roller-skate and smack each other in the face with plates full of whipped cream — while we listen, in voice-over, to a long treatise on spectacle. (The show incorporates text from several writers, including Guy Debord.) Eventually, they hold each other in a long, gorgeous partner dance that shifts genres and tones but maintains a thread of exquisite intimacy.

If it sounds like a heady, heavy cocktail, Those Moveable Pieces manages to leave a surprisingly delicate impression. In the center of it all is an attempt to redress, via two bodies sweating and connecting in space, three grave contemporary emergencies: “(1) A neglect of embodiment,” says the voice-over, “(2) An abuse of narrative … (3) A crisis of imagination.” I found myself thinking — strangely enough — of As You Like It’s Jaques. “Invest me in my motley,” he says, pleading for a jester’s uniform. “Give me leave / To speak my mind, and I will through and through / Cleanse the foul body of the infected world, If they will patiently receive my medicine.” Experimental theater can be clownish, obscure, nonlinear, and alienating, and it’s because it’s trying to jump-start the calcified perspective — to push us, if only for a moment, into seeing differently. It takes patience, and it’s strong medicine.