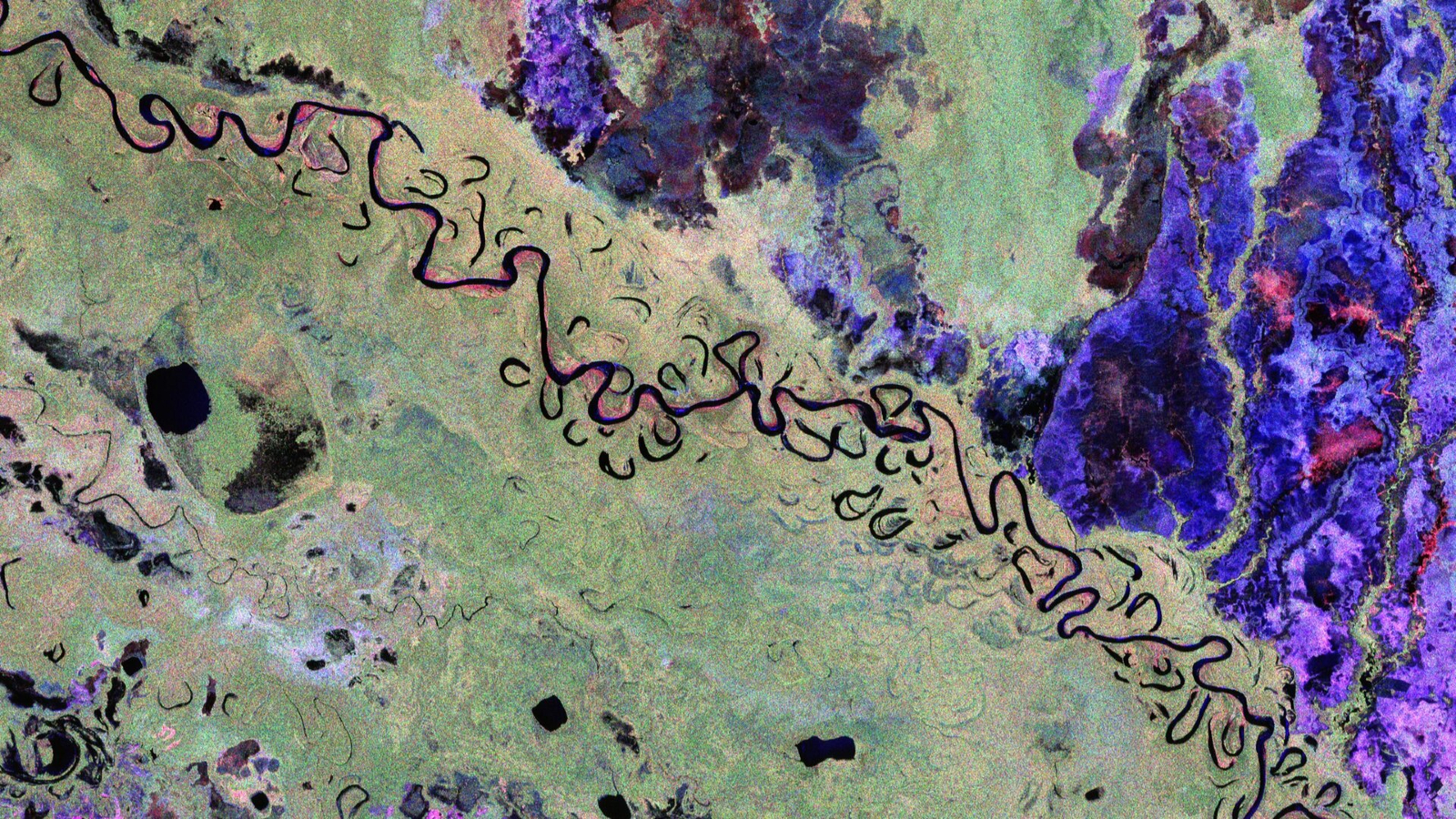

QUICK FACTS

Where is it? Great Dyke of Zimbabwe, central Zimbabwe [-18.6018258, 30.3435861]

What’s in the photo? A massive, ancient rock formation that is rich in valuable metals

Who took the photo? An unnamed astronaut on board the International Space Station

When was it taken? Sept. 30, 2010

This intriguing astronaut photo reveals the hidden beauty of the expansive Great Dyke of Zimbabwe, a massive seam of ancient magmatic rock that’s chock-full of valuable minerals.

Despite its name, the gigantic structure is not actually a dike — a vertical sheet of frozen magma that cuts through existing rock layers. Instead, it is a lopolith, which is similar to a dike but forms parallel to existing rock sheets and is both flatter and more lenticular, or saucer-shaped.

The Great Dyke is thought to be the longest continuous igneous intrusion, or structure of elevated magmatic rock, anywhere on Earth, according to the Zimbabwe Geological Survey.

The astronaut’s snap shows the southernmost tip of the structure, around 78 miles (125 km) from Bulawayo. In 1983, astronauts on board the space shuttle Challenger also captured a striking photo of the structure’s southern half, and in 2003, NASA’s Terra satellite imaged the lopolith’s entire length (see below).

Geologists think the lopolith formed around 2.5 billion years ago, when magma from Earth’s mantle gradually seeped upward through tectonic plate faults. This means the structure has existed for more than half of Earth’s roughly 4.5 billion-year history.

This magma was full of valuable minerals that are normally locked deep below Earth’s crust, which has made the area a hotspot for mining. Today, there are at least half a dozen major mines along the lopolith’s length, according to Mining Zimbabwe magazine.

The Great Dyke is full of important metals, including gold, nickel, copper, titanium, iron, vanadium and tin, according to the Earth Observatory.

However, it is best known for its expansive platinum deposits, which are collectively the third largest of their kind on Earth, as well as its unusually pure chromite, which contains high levels of chromium — a key component in the production of stainless steel, according to Mining Zimbabwe.

The Great Dyke is also rich in rocks that are used for sculpting, “resulting in an artist’s paradise akin to the Greek marble quarries,” local artist Michael Nyakusvora wrote on their website.

“The Great Dyke of Zimbabwe is more than a line on a map — it’s a lifeline of economic opportunity [and] a geological marvel,” according to Mining Zimbabwe.

A 2020 astronaut photo shows the oasis town of Jubbah lurking within a paleolake in the wind shadow of Saudi Arabia’s “two camel-hump mountain.”

The first false-color image from ESA’s newly operational Biomass satellite shows off a unique perspective of the rainforests, grasslands and wetlands in Bolivia.