A vaccine designed using “DNA origami” activated more of the key immune cells needed to fight HIV than did traditional vaccines built upon protein scaffolds, a new mouse study found.

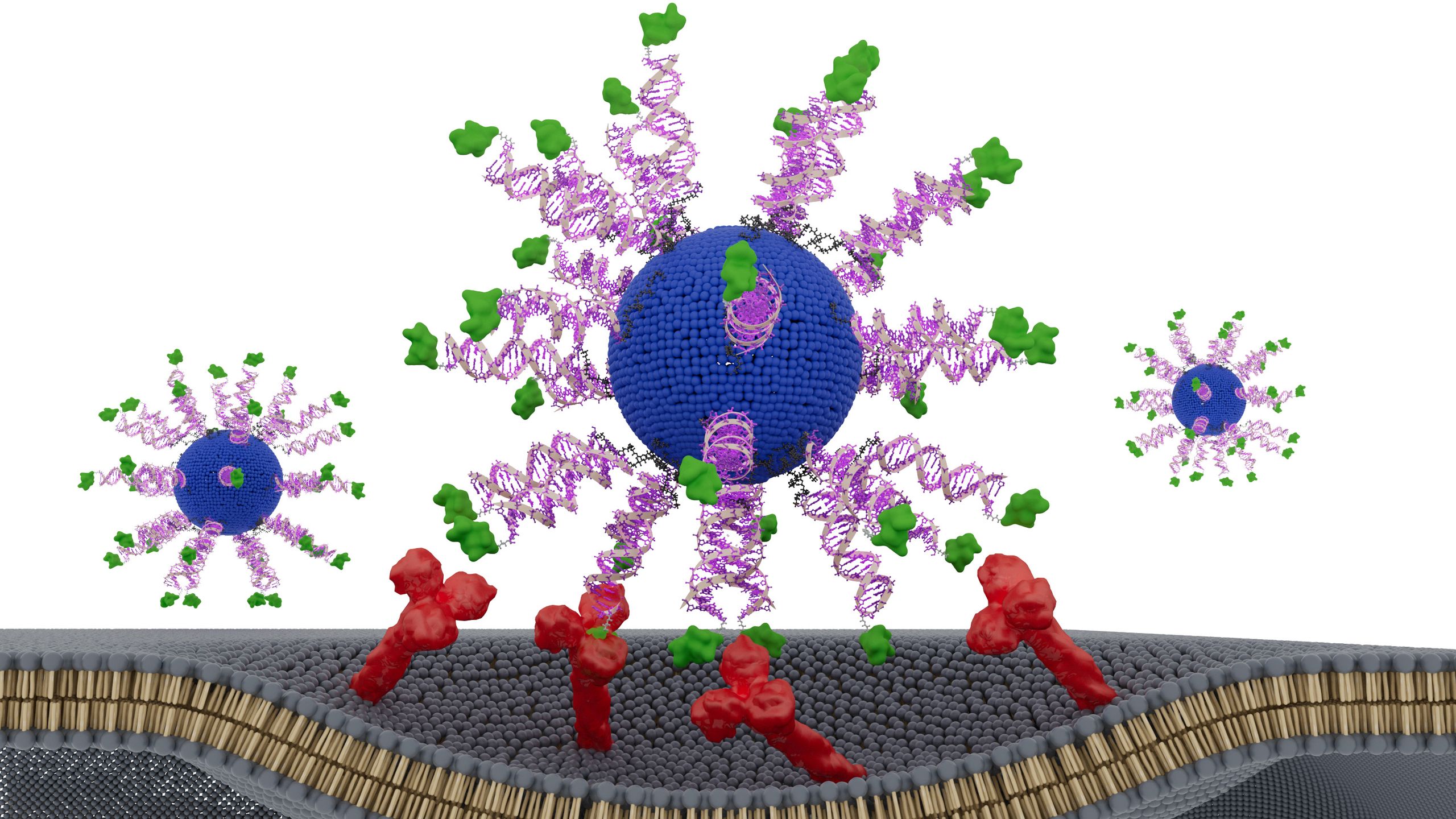

“DNA origami” refers to a precisely engineered, three-dimensional scaffold made of folded DNA that can hold and display viral antigens — bits of viruses that the immune system can recognize and attack.

Why could this origami approach be transformational? The answer may lie in how the DNA-based vaccines are seen by the immune system, compared to traditional vaccines.

How the DNA origami vaccine works

Conventionally, vaccines have relied on weakened or killed viruses to rouse immune cells to make antibodies against proteins found on that virus’s surface. By binding to the proteins, the antibodies block the virus from invading human cells and flag the germ for destruction by other immune cells.

This process imparts immunity by prompting the body to make “memory B cells,” which linger and get activated much faster if the same pathogen is encountered again.

But nowadays, rather than using whole viruses, many vaccines use only the surface antigens attached to synthetic, virus-like particles. These nanostructures mimic the size and geometry of viruses but cannot cause infection.

Most virus-like particles used today are built using protein scaffolds that the immune system sees as “foreign,” so they trigger an “off-target” antibody response against the scaffold itself. In some contexts, this may dilute the responses against the antigen, previous studies suggest.

In the new study, scientists replaced the protein scaffolds with a DNA-based scaffold and, by doing so, sharply reduced those off-target responses. This new vaccine design produced up to three times more of the important memory B cells than state-of-the-art protein nanoparticle vaccines did.

John Moore, an HIV researcher at Weill Cornell Medicine who was not involved in the work, described the study as “elegant.” It clearly demonstrates how eliminating scaffold-related immune responses pushes the immune response “in the right direction,” he told Live Science.

He cautioned, however, that it remains to be seen whether the same degree of immune focusing will occur in humans.

An edge on the competition?

HIV evades the immune system by constantly reshaping its surface proteins so that antibodies that work against one strain often fail against others. That is why HIV vaccine design has been “incredibly challenging,” said Adam Wheatley, an immunologist at the University of Melbourne who was not involved in the study.

What the vaccine needs to produce are “broadly neutralizing antibodies” against the virus, he said. These antibodies lock onto parts of the virus that barely change from strain to strain.

One example of such an antibody is called VRC01, which has been identified in a small number of people living with HIV whose bodies produce broad antibody responses. VRC01 targets a vulnerable region on HIV’s outer envelope called the CD4-binding site. This is the “key” the virus uses to enter human immune cells, and it doesn’t differ much between strains.

The challenge is that B cells that are capable of producing VRC01-like antibodies are extraordinarily rare in the human body, said Raiees Andrabi, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania who was not involved in the work. Activating those elusive cells “becomes an engineering problem,” he told Live Science.

To target these rare B cells, the researchers carefully engineered the vaccine using an HIV antigen on the DNA scaffolding. Developed about a decade ago, the antigen they used mimics the CD4-binding site and selectively binds the rare B cells’ receptors, thus initiating the production of broadly neutralizing antibodies.

The researchers got the idea to combine the antigen with DNA origami after testing the origami approach in an experimental COVID-19 vaccine. They’d found that the immune system showed virtually no response to the DNA scaffold.

“This property seemed especially useful for a case like HIV, where the B cells of interest are exceptionally rare,” first study author Anna Romanov, an immunology researcher at MIT, said in the statement.

They hypothesized that delivering the antigen on a silent scaffold could reduce the competition with other irrelevant B cells, thereby boosting the “on-target” response against HIV. And in the study, they found the silent-scaffold approach had indeed amplified the B cells that produce broadly neutralizing antibodies. (That said, they have not yet assessed how many broadly neutralizing antibodies actually get made; that should be addressed in future work.)

“We were all surprised” that DNA origami outperformed the standard virus-like particles used in eliciting the desired B cell responses, Bathe said.

In general, it’s unclear how bad it is for the body to generate an immune response against the scaffold, Wheatley said. But in the case of HIV, the desired B cells are so rare that even a modest off-target response seems to undermine the response against the target antigen.

The road ahead

The engineering of the DNA-origami vaccine was not straightforward; early versions produced weak immune responses. That was partly because, after injection, those vaccines failed to reach specialized immune cells inside the lymph nodes, where B cells train.

To correct this, the team redesigned the DNA particles to pack the HIV antigens more precisely and tightly. This enabled them to be carried into the right regions within the lymph nodes. The researchers also added a molecule to help activate T cells — immune cells help the critical immune response grow. This T-cell recruitment happens naturally with protein-scaffold vaccines.

“I think it is quite striking how efficiently they modified their DNA scaffold in a number of ways to get it to work,” Wheatley said. “I guess the major utility of it is [that] it’s really tunable.”

Beyond HIV, the study authors suggest that DNA origami could be applied to make vaccines against other rapidly mutating viruses, such as influenza, where the effectiveness of the vaccine might be improved by focusing the immune response it triggers.

However, it remains to be seen how well this technique will translate to humans. HIV vaccination is “very difficult” and might have multiple components to help develop the immune response over time, Andrabi explained, adding, “It’s not just going to be one or two shots.”

However, he said, “they have figured out the first step.”

Romanov, A., Knappe, G. A., Ronsard, L., Cottrell, C. A., Zhang, Y. J., Suh, H., Duhamel, L., Omer, M., Chapman, A. P., Spivakovsky, K., Skog, P., Flynn, C. T., Lee, J. H., Kalyuzhniy, O., Liguori, A., Parsons, M. F., Lewis, V. R., Canales, J., Reizis, B., … Irvine, D. J. (2026). DNA origami vaccines program antigen-focused germinal centers. Science, 391(6785). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adx6291