Researchers investigating a vulture nest in a cliff cave in southern Spain discovered an unusual piece of footwear — a grass shoe from medieval times. Further investigation of neighboring roosts revealed that generations of vultures had feathered their nests with other historical artifacts, including pieces of leather, cloth and string.

“The good conditions of the caves have allowed the artifacts to be preserved for centuries, suggesting that these nests are authentic natural museums,” study co-author Antoni Margalida, an ecologist at the Institute for Game and Wildlife Research in Spain, told Live Science in an email.

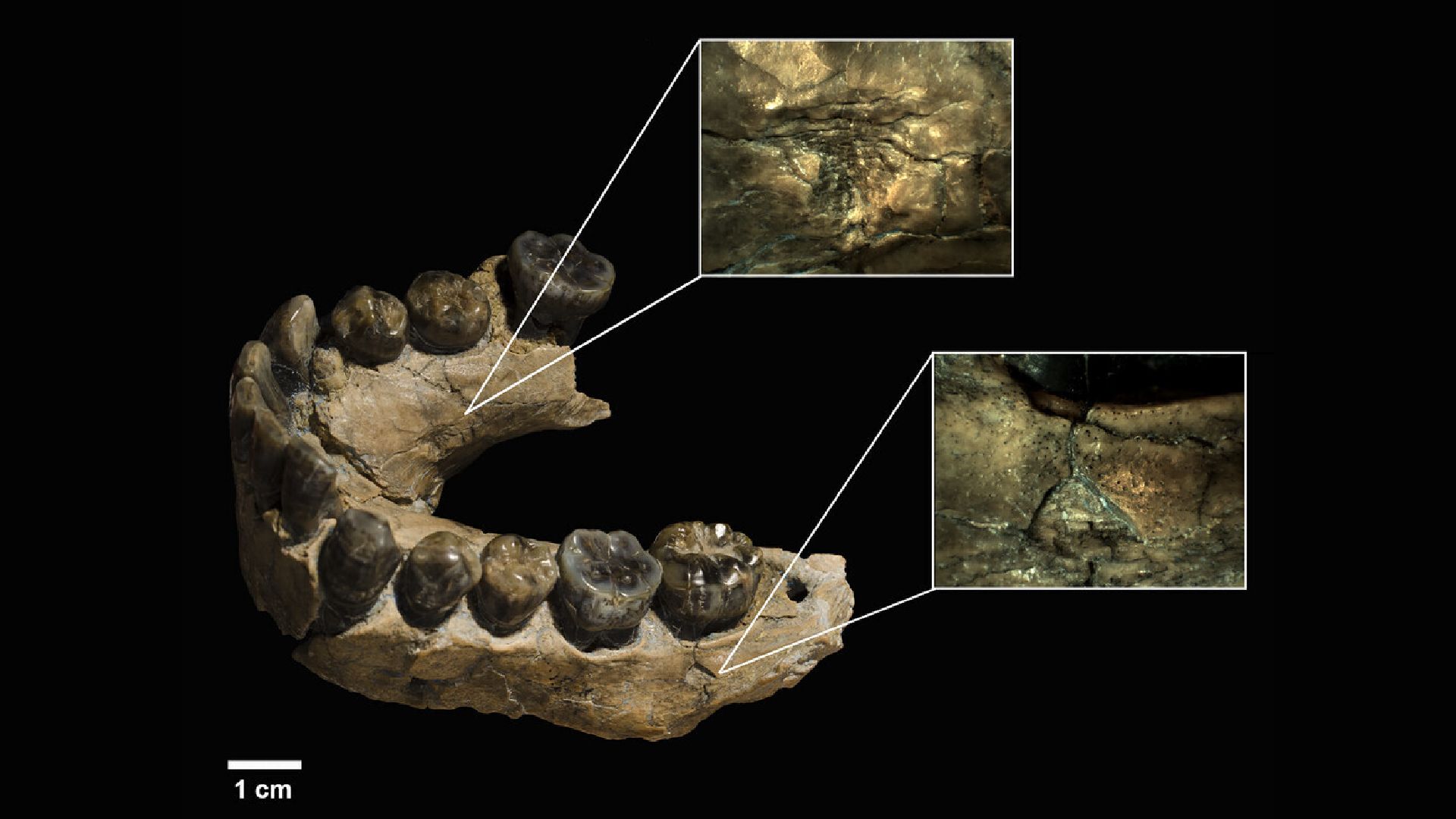

The vast majority of items the researchers found in the dozen vulture nests were bones, along with several hooves and eggshells from other animals. But roughly 9% of the remains were human-made, including a crossbow bolt, 72 pieces of leather, 129 pieces of cloth and 25 items made from esparto grass (Macrochloa tenacissima), including one intact shoe.

Esparto grass has been used for thousands of years to make shoes, including today’s espadrilles, which have a flexible sole made from esparto rope. Espadrilles were common peasant footwear in medieval Spain. When the researchers carbon-dated the grass shoe, they discovered it was nearly 750 years old.

“The remains of human origin were probably collected by the species during that period,” Margalida said, suggesting that the vultures were nabbing shoes from unsuspecting 13th-century peasants and not that the birds were robbing archaeological sites.

The same nest that produced the medieval espadrille also contained a fragment of sheep leather painted with red ocher. While it’s unclear which object the leather came from, the researchers carbon-dated it to 726 years ago, around the same age as the shoe.

Bearded vultures’ nests of hoarded materials can be a treasure trove of information for archaeologists, researchers wrote in the study, because their locations in Iberian caves and rock shelters with stable temperatures and low humidity make for good preservation of organic remains.

The researchers plan to continue their work on these historic nest sites.

“The next steps will be to identify all the remains – biological and human-made – and date the different layers of the nests by stratum in order to determine what period they belong to,” Margalida said.