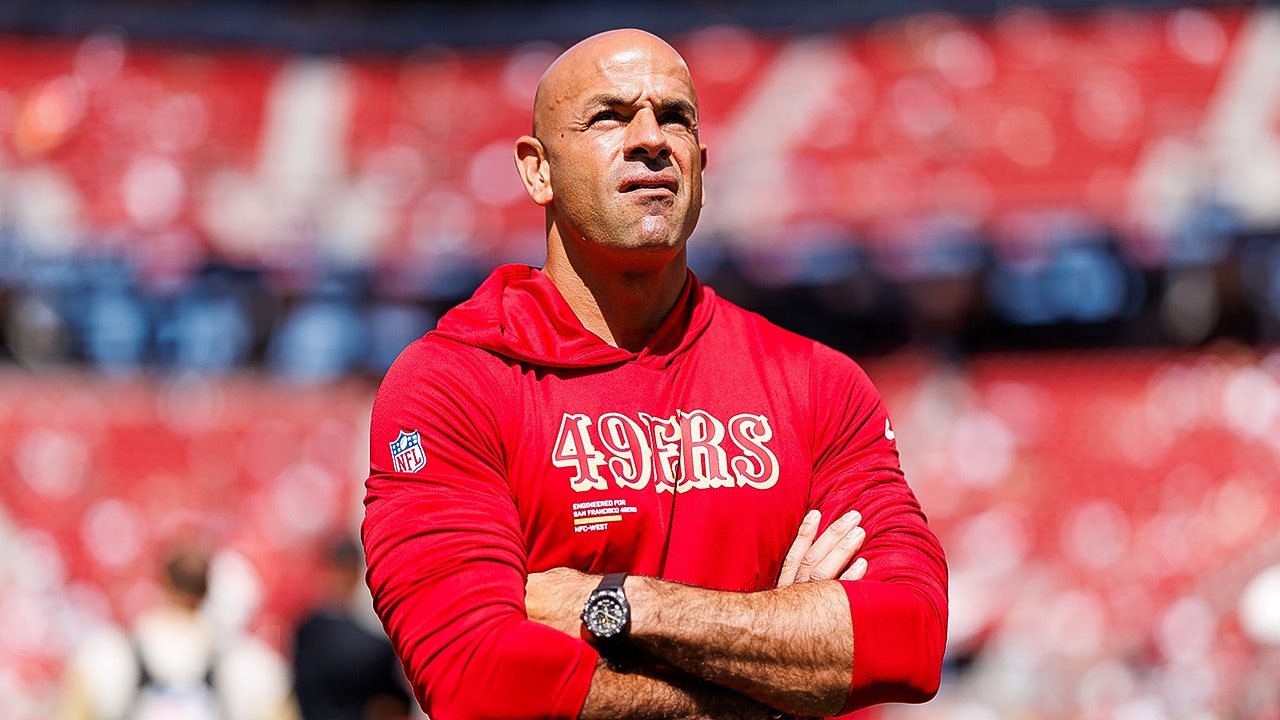

Chloë Grace Moretz and River Lipe-Smith in Caroline.

Photo: Emilio Madrid

One marker of the spurious issue play—a form the contemporary American theater features in surplus—is that it tends to be populated with puppets. Their inhabitants can, like the horror that is Tilly Norwood, look real, they can be loud or colorful or quirky, but ultimately they plug into a formula — they do what the playwright needs them to do.

That’s why it’s refreshing to come across a play like Preston Max Allen’s Caroline, the assured, affecting three-hander now getting its premiere at MCC under the emblematically thoughtful and ungilded direction of David Cromer. Allen is writing about something that’s in our newsfeeds daily, but crucially, that thing doesn’t flatten or predetermine his people. What he’s actually interested in are relationships, the interconnectedness of messy human beings. His characters are grappling with the consequences of broken trust and the agonizing question of how much we can truly protect anyone we love. The political resonance of his project arises not from an explicit statement of values but from a tender demonstration of complex, undeniable humanity.

“Can you not tell them I’m trans?” Allen’s title character asks her mother in the play’s second scene. “Can’t I just be a girl?” She is Caroline (the wonderful River Lipe-Smith). She’s 9 years old and she’s only just chosen her name and shared it with her mother, Maddie (Chloë Grace Moretz, doing raw, poignant work). Her question, in Lipe-Smith’s inquisitive piccolo of a voice, is heartbreaking in its blend of straightforwardness and desperate desire, as is her mother’s wavering response. Maddie is as gentle as she can be with her daughter, but she can’t quite say yes: “It just might be important for them to know exactly what’s going on.”

So far we’ve seen Maddie and Caroline in a shabby diner and a bland motel room; Lee Jellinek’s set is an assemblage of transient spaces, bleeding together as mother and daughter search for stability, for a place that will offer them more than just another brief stop on the road. The pair are on their way from West Virginia to Evanston, Illinois, and despite Caroline’s excitement over getting to eat gummy worms for dinner while wearing brand new Lilo & Stitch pajamas from Target, she can also sense that her mother’s nerves are shredded and that their lives are changing for good. They’re on their way to Maddie’s childhood home. Caroline has never met her grandparents — they don’t even know she exists. Maddie—baggy hoodies tossed over an array of old tattoos, clearly carrying a heavy amount of life for her 28 years—gradually attempts to fill her daughter in on her own youth, treading a tightrope between honesty and delicacy. “I was not a good kid,” she tells Caroline. “I started drinking when I was 15. And doing drugs … and when I was 17 I stole a lot of money, and I ran away.” In fact, Maddie robbed and ran not once but twice (“That’s pretty bad,” pipes Caroline after a beat; Lipe-Smith has excellent dry comic timing). Now, Maddie’s own child is in danger, and she needs help. Whether or not her parents will have anything left to give is the question.

Ostensibly centering Maddie’s own troubled past and the ramifications it might have for her and her daughter’s future is what makes Allen’s play as smart as it is. That Caroline is trans is simply a fact, a given circumstance that has to be navigated like any other while the characters struggle to make a life for themselves. Maddie frets over how her well-off, emotionally subdued Midwestern family will take the news, but no more than she worries about whether her mother, Rhea (Amy Landecker), will even agree to speak to her after almost a decade of estrangement. As for Caroline, her questions for Maddie are devastating precisely because they’re so practical: “Do I have to quit gymnastics?” she asks. “Where am I gonna go to the bathroom?” Her tone is steady, serious but not distressed — she’s a child trying to figure out the rules of the world. But every time Maddie’s shoulders tense or she takes a breath in response, fighting with all she’s got to stay confident and cheerful, we’re hit with a visceral reminder of just how cruel those rules often are, how many children this country is blithely endangering, and how many parents are trying not simply to affirm and love their kid but to protect them from all the consequences, daily and deadly, of a government that has anathematized them as a terrorist threat.

To watch Lipe-Smith’s Caroline cuddle in bed watching TV on her iPad, or bopping around to JoJo Siwa, or pensively finishing a Popsicle while sitting beside her grandmother at a museum, is to have the sheer malevolence of our current administration and its adherents thrown into sharp relief. No one talks much about politics in Caroline — it simply looms in every casual moment of this child’s life. (One brief, dismissive mention of party affiliation by Rhea is a well-built laugh line.) Instead, Allen crafts a more nuanced conflict not out of whether Maddie’s mother will offer to be a part of Caroline’s life, but of how. The wounds of Rhea and Maddie’s shared past have given rise to painful vigilance. Love now has terms and conditions.

“This is the result of boundaries that we set, and I don’t think it’s productive to dismantle those boundaries when you’re doing so well,” says Rhea to her daughter, her vocabulary crisp with therapy-speak as she offers Maddie a lifeline that comes with handcuffs. It’s easy to recoil at Rhea’s seeming chilliness, the Coldwater Creek sweaters and diminished reserves of compassion, but Allen makes sure that she’s no monster. While the heartbeat of the play remains with Caroline and Maddie, Rhea certainly earns our sympathy if not our approbation. Her daughter is an addict—“I am always one bad day away from all of that, you’re right,” says Maddie, shaking with emotion—and her own ability to trust has been shattered. How do you reconcile self-protection with what you owe your child? What if that child has hurt you, and herself, again and again? What if we can never really keep each other safe, no matter how much we love? How then, asks Caroline, do we keep on keeping on?

Caroline is at the Robert W. Wilson MCC Theater Space through November 16.