Scientists have been using ancient DNA to investigate questions about extinct animals since 1984, when researchers recovered two pieces of DNA from a museum specimen of a quagga, a zebra-like species that went extinct in the 19th century. Over the past 40 years, advancements in technology have allowed scientists to sequence older and older DNA from animals and plants, with the current record held by a 2.4 million-year-old Greenland ecosystem.

But could DNA potentially last even longer? Because DNA preservation depends on a huge number of environmental factors, scientists are still grappling with the question of how long DNA can theoretically and realistically last.

Michael Crichton’s sci-fi novel “Jurassic Park” (Knopf, 1990) — in which a billionaire founder of a bioengineering firm extracts dinosaur DNA from insects fossilized in amber and resurrects several extinct species — was an entry point into the world of ancient DNA for a generation of people, including scientists.

“People started looking for DNA in Cretaceous fossils” of organisms that lived 145 million to 66 million years ago, Gilbert said, “and the DNA turned out to be things like bacteria that weren’t that old.”

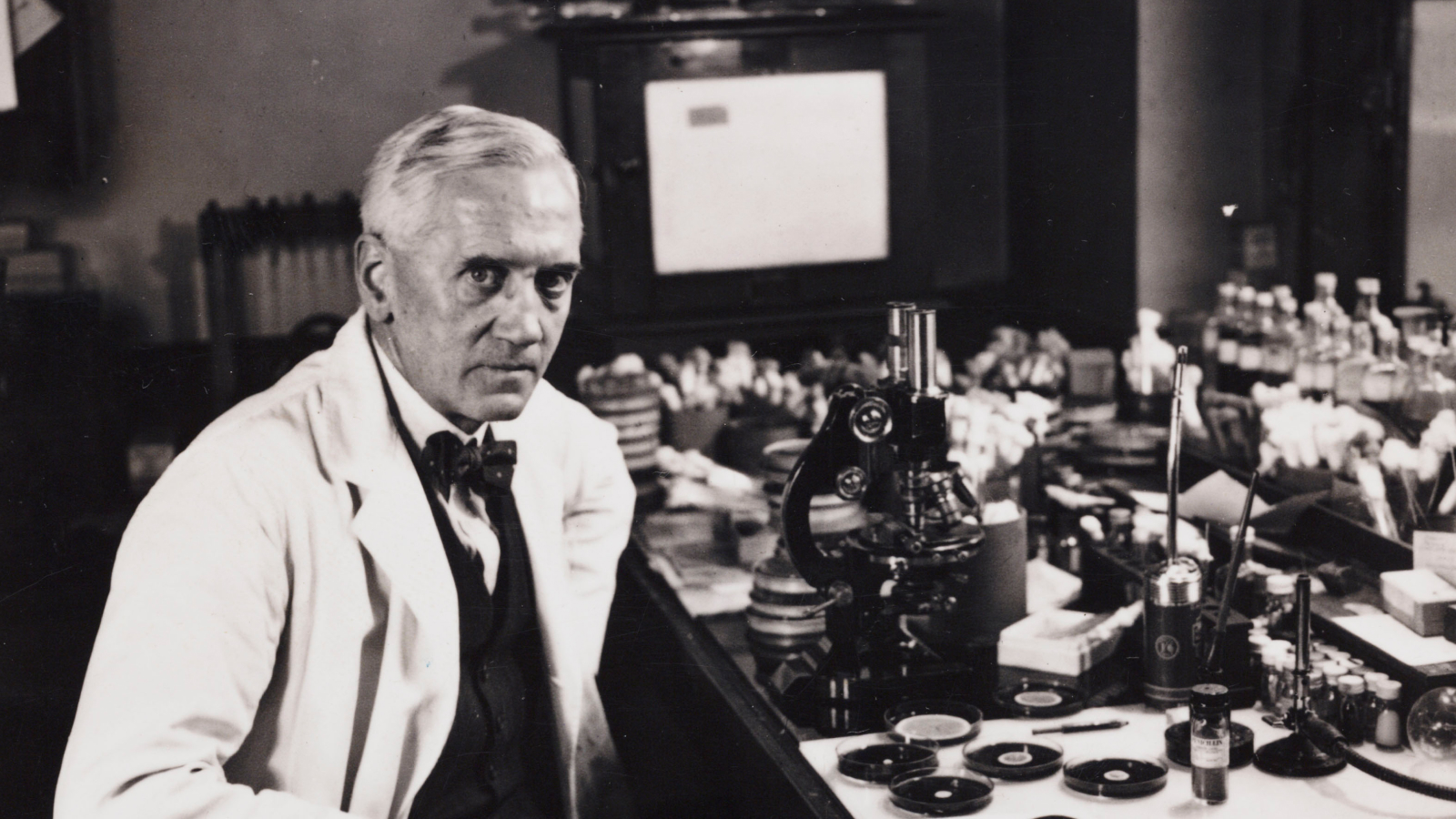

Gilbert co-authored a 2012 study that used statistics to model the “half-life” of DNA in bone and to check claims of the extraordinary survival of DNA in Cretaceous period specimens.

The team analyzed the mitochondrial DNA in 158 bones from extinct New Zealand moa birds that had been carbon-dated. By looking at how the DNA broke down over time, the team discovered that DNA’s “half-life” — when half of the DNA bonds in a sample would be broken — is about 521 years.

This model predicted that, under ideal conditions, DNA could survive for about 6.8 million years — not nearly long enough for Jurassic Park to become a reality.

“The best conditions for ancient DNA preservation are cold, dark, dry and recent,” Jennifer Raff, a biological anthropologist at the University of Kansas, told Live Science. “These permafrost conditions are where you can get the best DNA usually.”

This explains why the oldest DNA to date has been found in 2.4 million-year-old sediments in Greenland and why the oldest genome sequenced to date — from a mammoth that lived 1.2 million years ago — was found in Siberia.

This raises the question of what’s the oldest DNA from a human or close human relative. Humans evolved largely in geographic areas that are hot and damp, where DNA preservation is poor. This limits how much we can learn about our distant ancestors and related species from their DNA.

DNA from Neanderthals, our closest extinct human cousin, was extracted in 1997 from a 40,000-year-old Neanderthal discovered in 1856 in the Kleine Feldhofer cave in Germany. Meanwhile, the world’s oldest DNA from a human relative comes from Sima de los Huesos (“Pit of Bones”) in an underground cave in the Atapuerca Mountains of Spain. In 2022, researchers sequenced DNA from a thigh bone of a human relative that lived 400,000 years ago, suggesting that the group may have given rise to both Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Ancient DNA evidence from Africa, where humans evolved over millions of years, is currently sparse. Due to natural preservation issues, the oldest DNA from sub-Saharan Africa is only 20,000 years old and from modern Homo sapiens. Together with DNA’s predicted half-life, this means scientists are limited in investigating the genetics of our earliest ancestors.

Recent advances in paleoproteomics — the study of ancient proteins — are beginning to provide small amounts of genetic information from human relatives that lived 3.5 million years ago. But getting DNA from relatives like the australopithecines, a group that includes Lucy, is next to nil.

“I don’t think we’ll be able to get DNA from australopithecines,” which lived around 4.5 million to 1.2 million years ago, Raff said, “because those are all in Africa and the conditions are not ideal.” But it still may be possible to extract DNA from more recent hominins, a group that encompasses our close human ancestors and relatives.

“I’m much more optimistic about Homo erectus,” Raff said. “You’ve got Homo erectus in places where you could conceivably have good DNA preservation,” including the Republic of Georgia and China.

Even if experts find a place with ideal conditions for ancient DNA preservation — cold, dark and dry — there’s one final parameter that’s important to consider, Gilbert said: whether the surviving DNA is meaningful.

“There’s a minimum length of DNA sequence you need that you can uniquely identify,” Gilbert said. “If you take a book and cut it up into chapters, you can identify the book. If you cut it up into words, it’s much harder. Cut it up into letters, it’s impossible.”

Although 2.4 million years is the current record for the oldest meaningful DNA to be sequenced, Gilbert said, older DNA may be found in the future, perhaps under Antarctic ice sheets.

“To be honest, had I been asked in 2003 how long DNA could last, the absolute wisdom of all the people in the know would have been 100,000 years,” Gilbert said. “So we’re off by a factor of 20 already.”