MAHARASHTRA, INDIA — When Babytai Suryavanshi first noticed a few scaly patches on her right forearm, she ignored them for three months, thinking it was an infection that would heal on its own.

While working in the sorghum fields last year, she noticed the patches had become more raised and red and that they burned.

What 76-year-old Suryavanshi didn’t know, and what researchers are now uncovering, is that air pollution can play a role in triggering and worsening this disease.

Around 99% of the world’s population is exposed to air that doesn’t meet the World Health Organization’s air quality guidelines. And in 2021, 42.98 million people had a diagnosed case of psoriasis. But studies suggest many people may go undiagnosed in part because it’s easily mistaken for other conditions and more difficult to spot on darker skin tones; some estimates suggest 125 million people are affected globally.

For Suryavanshi, the link between her skin condition and pollution became clear after the doctor asked her to pay attention to her environment. For over 30 years, she worked at a sugarcane planting nursery near her home in Jambhali village in Western India. She quit last year because the constant smoke from burning sugarcane residue and plastic seedling trays was triggering repeat flareups, she said. Now, she works on farms, but that also carries risks because nearby factories often expose her to polluted air.

An emerging link

Air pollution is a term that encompasses a wide variety of chemicals and particles that humans spew into the air through industrial activities, from running factories to driving cars. It can encompass everything from wildfire smoke to smog. It contains fine particulate matter of various sizes — including PM2.5, which is smaller than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5), and PM10, smaller than 10 micrometers — as well as chemicals like nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOX).

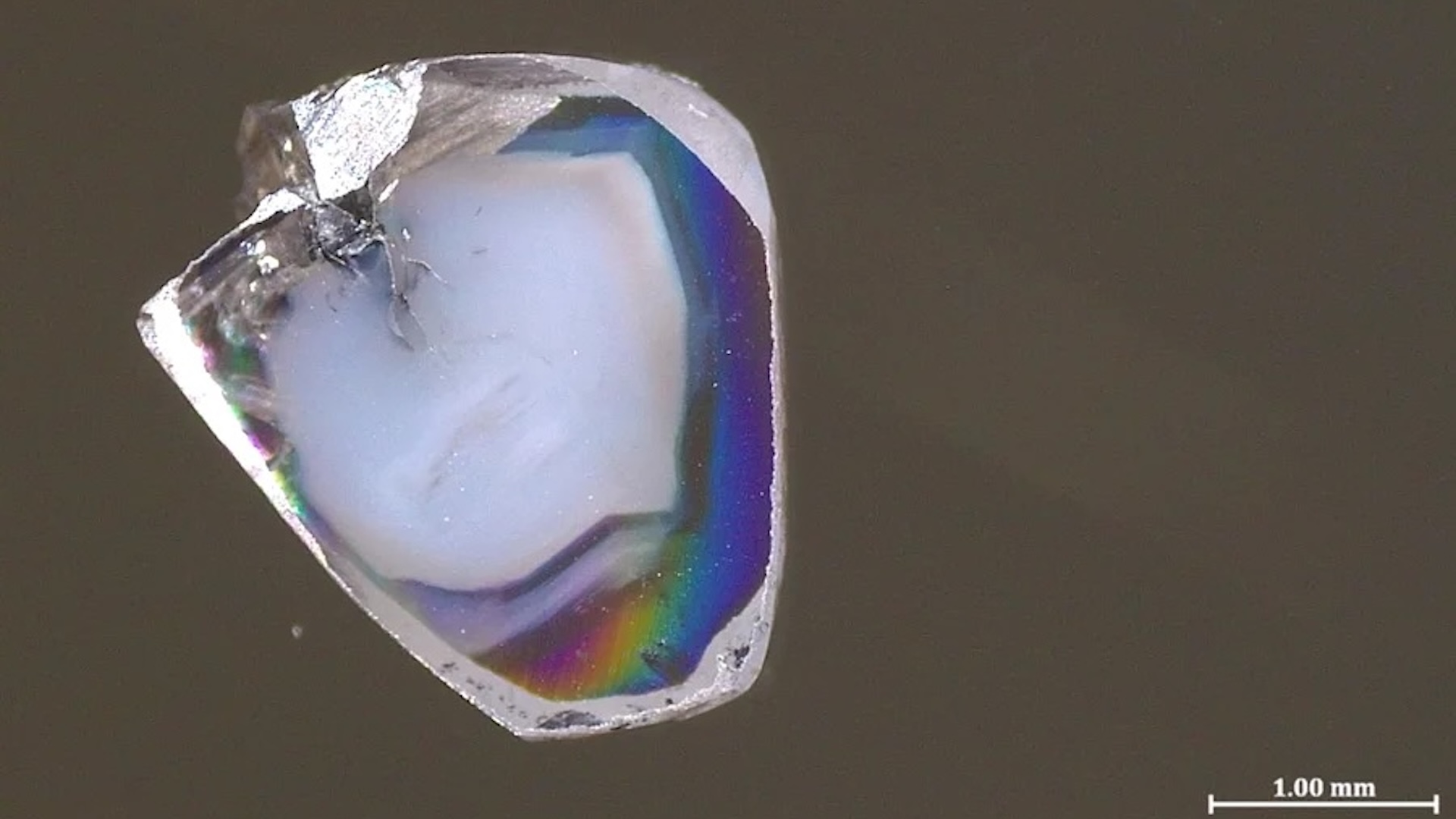

Psoriasis, meanwhile, is an autoimmune condition in which the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues, namely skin cells. People usually have flareups of the condition, which are treated with creams, phototherapy or medicines that calm the immune response. The condition tends to run in families, so there is a genetic component that makes people more vulnerable.

But genes aren’t the only factor at play. The link between psoriasis and pollution has been found in several studies from around the world.

For instance, one analysis included nearly 285,000 people from the U.K. Biobank, a repository of health data and biological samples from U.K. adults, who were followed for 15 years. It revealed that long-term exposure to pollution may accelerate biological aging. They measured this aging using the PhenoAge algorithm, a tool known as an “aging clock” that estimates the body’s biological age, rather than just the number of years lived. This estimate indicates whether the body is aging faster or slower than an average, healthy baseline, and can also predict the risk of death from any cause or incidence of age-related diseases, like cancer.

Increases in this aging metric were tied to an increased risk of psoriasis, with each one-year increase in biological age tied to a 5% higher risk of the condition.

Another study, from Verona, Italy, found a temporal link between high-pollution days and psoriasis flareups. The study tracked pollution levels in the city in the days leading up to patients visiting the clinic to get treatment for psoriasis, taking an average of the pollution levels over the prior 60 days. The results showed that high exposure to air pollution in that timeframe, defined as passing a certain threshold of PM2.5 and PM10, increased the odds of visits for these flare-ups.

Furthermore, a 2024 study of more than 3,600 Americans investigated the relationship between psoriasis and urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) metabolites, components of air pollution formed during the burning of coal and oil, garbage and other carbon-based substances. People with higher PAH metabolite levels — indicating higher exposure in recent days — were 83% more likely to have psoriasis. Another U.S. based study, published in 2023, linked clinical visits for psoriasis to pollution caused by wildfire smoke.

Even short spikes in pollution may raise the risk of psoriasis-related medical visits. A five-year evaluation in Nanchang, China looked at levels of several pollutants, including nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide, and found a linear relationship between rises in pollutant levels and psoriasis-related visits to the doctor. The degree of increased risk and the lag-time between exposure and an outpatient visit varied depending on the specific pollutant being measured, but the lag was typically on the order of a few days to a week.

Causes unraveled

These studies point to some sort of link between pollution and psoriasis, but scientists are now probing deeper into exactly how polluted air triggers or worsens the condition. And the answers, while complex, are beginning to emerge.

Some studies suggest small particles in pollution may directly damage the outside barrier to the body, disrupting the skin both physically and chemically, Dr. Nidhi Singh, an environmental epidemiologist and postdoctoral researcher at IUF–Leibniz Research Institute for Environmental Medicine in Germany, told Live Science in an email.

For instance, it’s been shown that fine particulates cause changes to proteins and fats in the skin, said Singh, who authored a paper on genetic and environmental risk factors for psoriasis. These changes may disrupt enzymes in the body’s antioxidant defense system, which cleans up tissue damage caused by free radicals, such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. It’s also possible that air pollution fuels increased production of reactive nitrogen species in human tissue, specifically in skin, Singh added.

Dr. Paolo Gisondi, an associate professor of dermatology at the University of Verona who co-authored the Italian study, told Live Science that while the exact biological mechanism is not fully understood, “we can speculate that air pollutants trigger inflammation in the skin by activating immune cells and driving the release of inflammatory molecules.” This abnormal immune activation may then lead to psoriasis.

Singh also noted that, in lab dishes with stem cells that are developing into skin cells, ultrafine particles — the tiniest component of air pollution measuring less than 0.1 micrometer each — can increase the activity of genes associated with inflammation and psoriasis. In lab dishes, ultrafine particles can also disrupt the normal development of keratinocytes, the main cells in the outer skin layer.

A paper published this year looked at U.K. Biobank data and pinpointed a specific gene that may be involved in the mechanism: ZMIZI. This gene typically helps regulate the immune system and inflammation and air pollution is tied to changes in its activity. ZMIZ1 acts as a dial, fine-tuning inflammation levels. However, air pollution can keep this dial locked in the “high” position, causing inflammation to ramp up and increasing the likelihood of autoimmune diseases like psoriasis, the study found.

What can be done?

At an individual level, people can reduce their pollution exposure by staying indoors on high-pollution days and using air purifiers, Singh said. And if they have to go outside, they can try to limit how many of these small particles penetrate their skin and hair follicles by covering exposed body parts with protective clothing. They can also regularly cleanse or exfoliate with products that remove particle buildup from the skin, Singh added.

But Singh emphasized the need for broader regulatory action. In addition to passing rules that reduce air pollution, governments should develop stronger early warning systems for high-pollution days, which can help people know when to stay indoors.

For residents like Suryavanshi, taking steps to avoid her psoriasis triggers is challenging.

There are more than 100 small and large sugarcane nurseries in their village, each of which produces pollution, she said. Like others in her neighborhood, she also heats water for bathing every day on a wood-burning stove, which exposes her to additional smoke pollution.

Last month, her husband, 78-year-old Mahadev Suryavanshi, was also diagnosed with psoriasis, but they can’t afford to pay for treatment right now. Each day, he endures a burning and itching sensation on his face that never subsides.

“It’s got something to do with the polluted air,” he speculated.