Scientists seeking ways to amp up the capabilities of solar power generators have discovered a method that can boost their efficiency by a factor of 15.

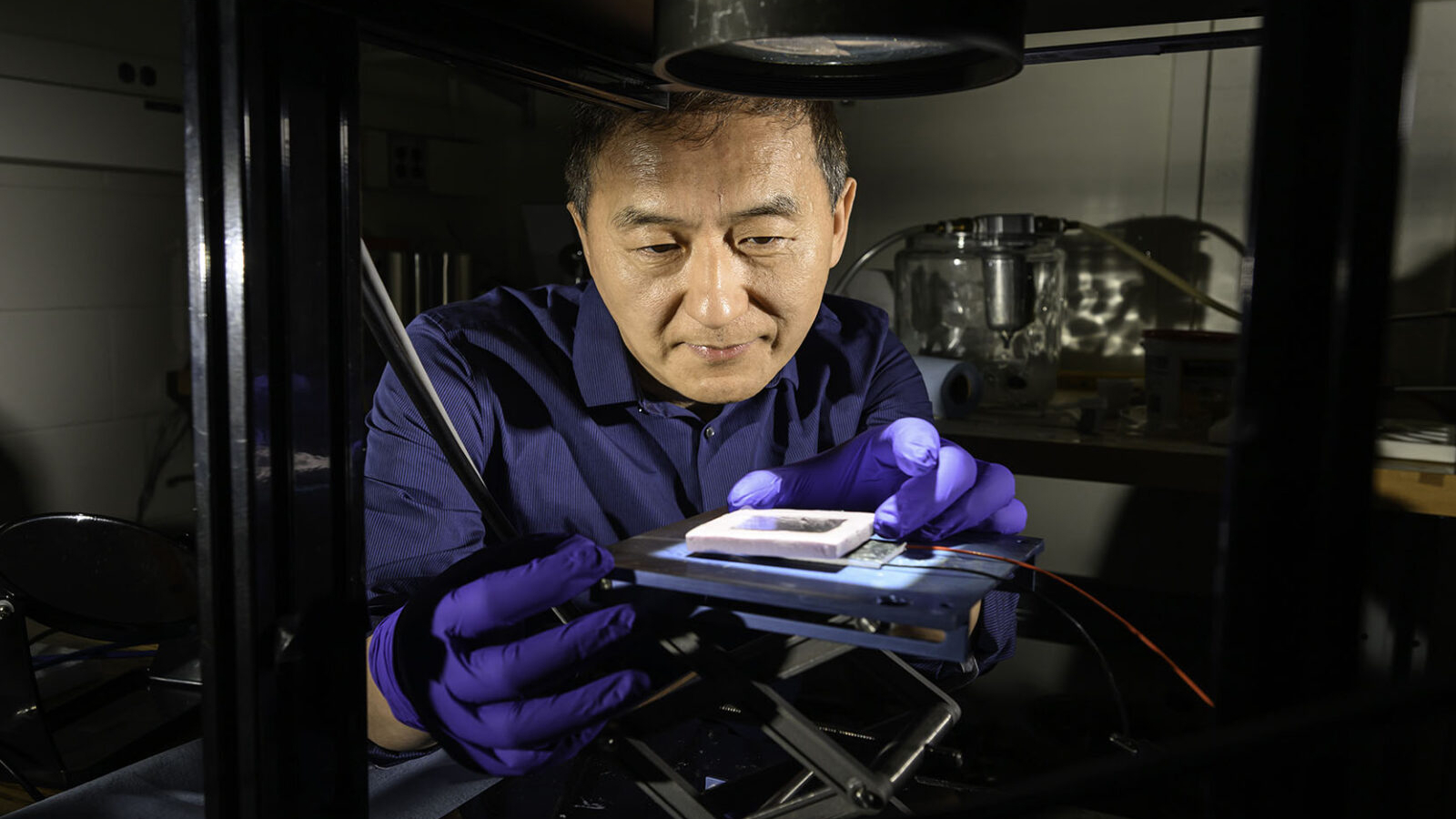

The breakthrough lies in a unique, laser-etched “black metal” developed by researchers over the past five years, which they now hope to use in solar thermoelectric generators (STEGs).

STEGs are a type of solid-state electronic device that converts thermal energy into electricity via the Seebeck effect — a phenomenon that occurs when the temperature difference between materials displaces charged particles and creates an electromagnetic force (EMF), or voltage.

A STEG contains semiconductor materials sandwiched between a “hot” and a “cold” side. When the hot side is heated — either by the sun or another thermal energy source — the movement of electrons through the semiconductor material creates an electric current.

The challenge with existing STEGs is that they are hugely inefficient, converting less than 1% of sunlight into electricity. This stands in contrast to the photovoltaic solar panels you’ll typically find attached to people’s homes, which convert around 20% of the light they receive into electricity.

Related: Nanoparticle breakthrough could bring ‘holy grail’ of solar power within reach

However, in a new study published Aug. 12 in the journal Light: Science and Applications, researchers used laser-treated metals, also known as “black metal” due to their deep, inky-black appearance, to boost the energy efficiency of a solar thermoelectric generator by a factor of 15.

Laser treatment

The method involved blasting a piece of tungsten with extremely fast and precise laser pulses to etch microscopic grooves into its surface. These “nanoscale etchings enabled the tungsten to absorb more thermal radiation and hold onto it for longer.

The laser pulses also have the effect of turning the surface of any metal pitch black, increasing their capacity to absorb heat. The researchers then covered the black tungsten with a piece of plastic to create a “mini greenhouse” that trapped even more heat.

For the cold side of the STEG, the scientists took a piece of regular aluminum and again blasted it with laser pulses. The tiny etchings in the metal created a “super-high-capacity micro-structured heat dissipator” that the team claimed was twice as efficient at dissipating heat versus a typical aluminum heat sink.

To test the system, the researchers used it to power an LED under simulated sunlight. A typical STEG couldn’t illuminate the LED even when exposed to light 10 times stronger than normal sunlight. With both sides treated using the black metal, however, the device lit the LED at full brightness under light five times stronger than normal sunlight — equating to a 15-times increase in power output.

While it likely won’t be replacing solar farms any time soon, the technology could eventually be used for low-power wireless Internet of Things (IoT) sensors or wearable devices, or serve as off-grid renewable energy systems in rural areas, the researchers said in a statement.

“For decades, the research community has been focusing on improving the semiconductor materials used in STEGs and has made modest gains in overall efficiency,” Chunlei Guo, study co-author, professor of optics and physics, and senior scientist at Rochester University’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics, said in the statement.

“In this study, we don’t even touch the semiconductor materials — instead, we focused on the hot and the cold sides of the device instead. By combining better solar energy absorption and heat trapping at the hot side with better heat dissipation at the cold side, we made an astonishing improvement in efficiency.”