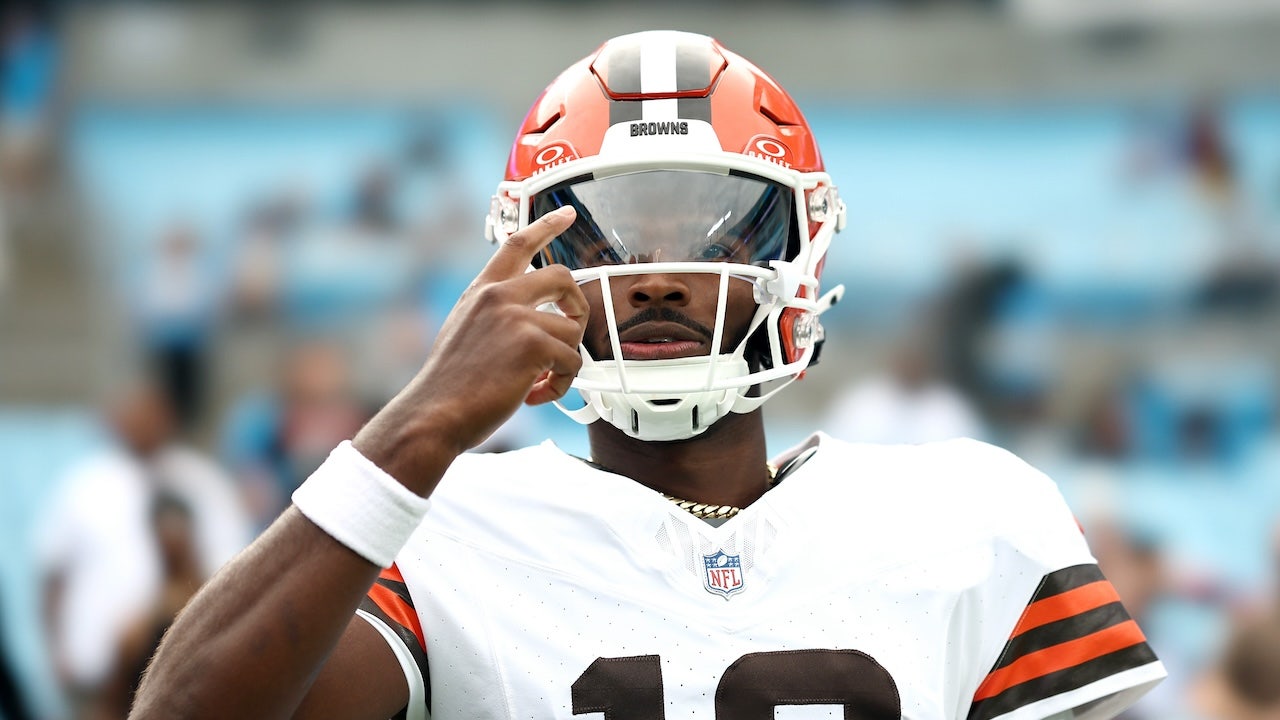

Elizabeth McGovern as Ava Gardner in Ava: The Secret Conversations.

Photo: Jeff Lorch

The visage of a Hollywood siren haunts Ava: The Secret Conversations, Images of her famous pursed lips and hourglass silhouette are projected onto the walls of the set in between scenes. Ava Gardner was a mid-century bombshell as famous for her relationships with the likes of Mickey Rooney, Artie Shaw, and Frank Sinatra as for her films, and by the late 1980s, when the play is set, her own star image seems to oppress her. Hard up for cash, she’s reluctantly agreed to write a memoir, though she’s wary about the man who’s been hired to ghostwrite it. “I either write the book or sell the jewels,” she tells him, “and I’m kinda sentimental about the jewels.”

That line, a great example of an old-fashioned diva simultaneously destabilizing and clinging on to a certain star image, comes from Peter Evans’s book Ava Gardner: The Secret Conversations, which forms the source material for the play. From 1988 to 1990, Evans, a British celebrity journalist, interviewed Gardner at her home in London for that memoir. Suspicious and mercurial as life and hard drinking had made her, she eventually fired him. Evans’s book wasn’t published until 2013, well after Gardner’s death and just after Evans’s. You can see why Elizabeth McGovern, who both wrote the script and stars as Gardner, latched on to the material, with dialogue like the jewels line. It’s a charged, if highly familiar, dynamic: the push and pull between subject and journalist, and between the crushing weight of a subject’s celebrity and her obscured “real” and “secret” self. That tension underlies pretty much every celebrity profile, and films like Almost Famous and, as the gothic quality of Moritz von Stuelpnagel’s directing will very much remind you, Sunset Boulevard. “You can sum up my life in a sentence, honey,” McGovern’s Gardner announces to Aaron Costa Ganis’s Evans, launching into another direct quote from Gardner that has its own air of Norma Desmond: “She made movies, she made out, and she made a fucking mess of her life, but she never made jam.”

The play makes the most sense as a vehicle for McGovern, who relishes the chance to mix up her own star image a bit with every successive “fuck.” Her Gardner swears like a sailor, then confronts Evans after the fact, demanding that he tidy up her language and make her look like a lady. McGovern, meanwhile, may have launched her film career as a naturalistic ingénue in Ordinary People and Ragtime, but lately, she’s become associated with the period starch of Downton Abbey. Here, she tacks crosswise from Lady Cora, playing someone with a comparable level of grandeur but also a tempestuous and brassy core. She prowls the stage like a wounded panther, toying with her prey and defensively licking her wounds. McGovern’s got a sadder and sweeter aura than Gardner, or at least than the constructed fatale character that Hollywood cast Gardner to play onscreen, and it contributes to the notion of seeing a woman shorn from the glamour she once could command. Both actress and character are in the shadow of a different mythological thing — literally, given the projections.

If McGovern herself is punching above the customary weight of a celebrity-playing-celebrity bioplay — or even an Oscar–winning biopic performance, if we force ourselves to remember Judy — that’s not enough to liberate Ava from the clichés of the form. In her script, McGovern identifies the shifting power dynamic between star and biographer: She needs him for the money; he needs her for the dirt. Gardner doesn’t want the book to focus solely on her love affairs, and Evans tries to assure her that he’ll get the full picture of her life while simultaneously taking calls from an editor who demands he question her about Sinatra’s penis size. If she’s writing from the position of being an actress herself, McGovern is remarkably understanding of the plight of the celebrity journalist, and she gives Costa Ganis good material in the tension between human sympathy and a venal desire for a scoop. (In flashback scenes, he also pulls off some crowd-pleasing imitations of Gardner’s exes.) Though it wasn’t the focus of the real Evans, Gardner’s cinematic art goes underdiscussed. Her films, like Barefoot Contessa and Show Boat (in which she was dubbed, as she complains), are mentioned but not lingered upon. Gardner is presented as self-conscious about her acting talent, untrained as she was, but the play misses something, as the character of Evans does, in focusing so much on the famous tabloid headlines.

If there are great revelations about the real and secret Ava Gardner to uncover, Ava itself doesn’t find them. That’s likely because the real Gardner didn’t provide them to the real Evans. Both play and book seem to end midstream, much as the actress soured on her interviewer in real life. Though he did eventually secure the blessing to publish from her estate, it seems unlikely she would have been happy with its contents. And, constrained as they are by that source material, McGovern and von Stuelpnagel opt for letting Gardner exit the narrative into her star persona in a grand bit of staging at the end of the play. They don’t make it a triumphant choice, but I did again think of Sunset Boulevard. She is ready not for a close-up but to be seen at an admiring distance, in a wide shot.

At the SoHo Playhouse in Can I Be Frank?, the comedian Morgan Bassichis is also speaking as an icon from the past, albeit a vastly less well-known one, and achieving far more vigorous results. In their solo show, Bassichis re-creates the material of Frank Maya, a gay performance artist, musician, and comedian who chased fame in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Maya made it near the edge of mainstream success — he was the first openly gay stand-up to appear on MTV and taped a half-hour for Comedy Central before dying of AIDS in 1995. He and his work are mostly forgotten, unheralded, and worth uncovering; Bassichis discovered it while at an art residency (“where you go to have sex with other people”). “This show is my attempt to try to pass on my obsession to you, to make sure everyone knows the name Frank Maya,” Bassichis says, preening in their sense of do-gooderness. “And if they have to learn my name, too, along the way, let go and let God.”

Morgan Bassichis as Frank Maya in Can I Be Frank?

Photo: Emilio Madrid

Can I Be Frank? is a deftly constructed turducken of a one-person show, with one comedian’s act stuffed inside another. Bassichis starts out by reproducing one of Maya’s “rants” verbatim, a tirade excoriating Liberace for staying in the closet while dying of AIDS. A few lines into that, Bassichis shifts back into their native persona, which is reedier and more deferential than the intensity with which Maya worked the stage. As themselves, Bassichis apologizes for screaming at the audience, gets around to some housekeeping in explaining who Maya actually was, and then winds their way back to that Liberace rant again. Though Bassichis poses as superficially messy — “This is not some sort of ‘finished, complete, perfect’ work in the antisemitic sense,” they announce early on while getting tangled in the microphone cord —there’s a deeper dance at work in this thing. It’s fitting, considering Can I Be Frank? is directed by Sam Pinkleton, a director and choreographer doing a lap of queer solo shows this summer after winning a Tony for Oh, Mary! with this one-person show and Josh Sharp’s ta-da!. Bassichis is interested in all the ways Maya’s work does and doesn’t overlap with their own postures and artistic fascinations: They re-create some of Maya’s bits, one of which involves dispersing prewritten questions to members of the audience, and let the two personae blend together. Bassichis’s rant about the disappointments of hookups suddenly transforms into one of Maya’s. You can watch that one online, though I’d hold off until you’ve let Bassichis, who comes across as the most eager TA in a college lecture course, introduce you to Maya first.

Like a lot of solo shows of the moment, Can I Be Frank? is aware of the attention economy of this business. Bassichis jokes throughout the show about how this is all a gambit to land a bigger mainstream gig, maybe thanks to “A24’s nonbinary comics division.” Recursive self-awareness like this can trap a performance in a feedback loop, but Bassichis finds heft in thinking about what actual mainstream fame might mean to a gay comedian, both in Maya’s time and now. Maya had a joke about telling his dad that “the only cure for being gay is fame,” which Bassichis admits they initially misunderstood as about how gay people crave attention, not, as originally intended, about how anyone gay and famous would have to be in the closet. Bassichis admires, too, how insistently selfish Maya could be, even in the context of an epidemic. People were starting to plan ACT UP demonstrations, and Maya was going on about how annoying it is when a guy suddenly cools off after an incredible first date. Can I Be Frank? becomes a furious and poignant argument for the good of frivolity. “He had a kind of selfishness to him that was political,” Bassichis says, quoting Maya’s friend Eileen Myles. There’s real force in confronting a society that would prefer to erase people like him, then or now, and saying, No, I will not shut up, and, yes, I will continue to discuss being fucked in graphic detail. That’s a noble thing to do and a narcissistic thing to do and just a painfully human thing to do, which makes it all the more worth dramatizing. Let’s celebrate Frank Maya for it, and if we have to celebrate Morgan Bassichis along the way, sure, why not?

A third act of theatrical resurrection is happening in a church in Fort Greene, where a widow is trying to better understand the sudden loss of her husband. In Bubba Weiler’s play Well, I’ll Let You Go at the Space at Irondale, Quincy Tyler Bernstine plays Maggie, a woman who has found herself adrift. Somewhat like Ava or Let Me Be Frank, the play deals with a celebrity of a kind, though at an even smaller scale than Maya: Maggie’s husband, Marv, a gregarious and open-hearted lawyer, was well-known in their small midwestern town. He died in a manner — Weiler initially withholds the circumstances — that has only made him more prominent. In a string of two-handed scenes, Maggie confronts a series of visitors all connected to Marv, whether they’re family members and friends or, in the case of a funeral-home employee played by Constance Shulman, just looking to make a deal.

It’s a parade of downtown theater actors — all across from Bernstine, herself an immensely watchable and implosive presence onstage. Maggie has lost some crucial load-bearing element inside of her, and in the audience, you feel yourself pulled to her in sympathy. In successive scenes, she and we meet with a guest who has overstayed his welcome (Will Dagger at his itchiest); Maggie’s sister, Julie (Amelia Workman, nailing the abrasive quality of a competitive sibling ); and Julie’s husband (Danny McCarthy, stolid as ever), as well as more figures whose identities shouldn’t be spoiled (played by the great Emily Davis and Cricket Brown). Stitching things together, Michael Chernus, who has been on a streak of television like Severance, is back and warmly ursine onstage as a narrator who very much resembles Our Town’s. Jack Serio’s spare direction, too, will remind you of that play, especially David Cromer’s production. (How could you not have Thornton Wilder on the mind when thinking about death in a small town?)

Quincy Tyler Bernstine and Will Dagger in Well, I’ll Let You Go.

Photo: Emilio Madrid

If Weiler’s construction provides the opportunity to see a series of fine actors at work with delicate tête-à-têtes, the neatness of the structure constricts some of the feeling. It’s hard not to see some turns of the plot before they arrive, and given the presence of a semi-omniscient narrator, you’re also more likely to notice what’s being withheld from you. Weiler’s careful parceling out of new developments develops a repetitive quality. That may well mimic the dulling effect of grief, though it keeps Well, I’ll Let You Go within a thin and cool tonal spectrum. As a director, Serio has made a name for himself with these kinds of actor-forward, hyperintimate, hyperreal stagings — Uncle Vanya in a loft — and this is a case where minimalism comes across as an affectation. The glasslike calm flattens the latent midwestern dark comedy in Weiler’s script, especially in the circumstances of Marv’s death, which, once revealed, might be better sold with a dose of bleak humor. In the moments where Well, I’ll Let You Go does break its ice, it reveals a moving warmth, especially when Chernus and Bernstine speak with each other. The two actors are like repelling magnets, contrary in mode and bearing, and yet they seem to answer each other. She pulls inward; he pushes out. It’s a match that’s somehow exactly right.

Ava: The Secret Conversations is at New York City Center through September 14.

Can I Be Frank? is at the SoHo Playhouse through September 13.

Well, I’ll Let You Go is at the Space at Irondale through August 29.