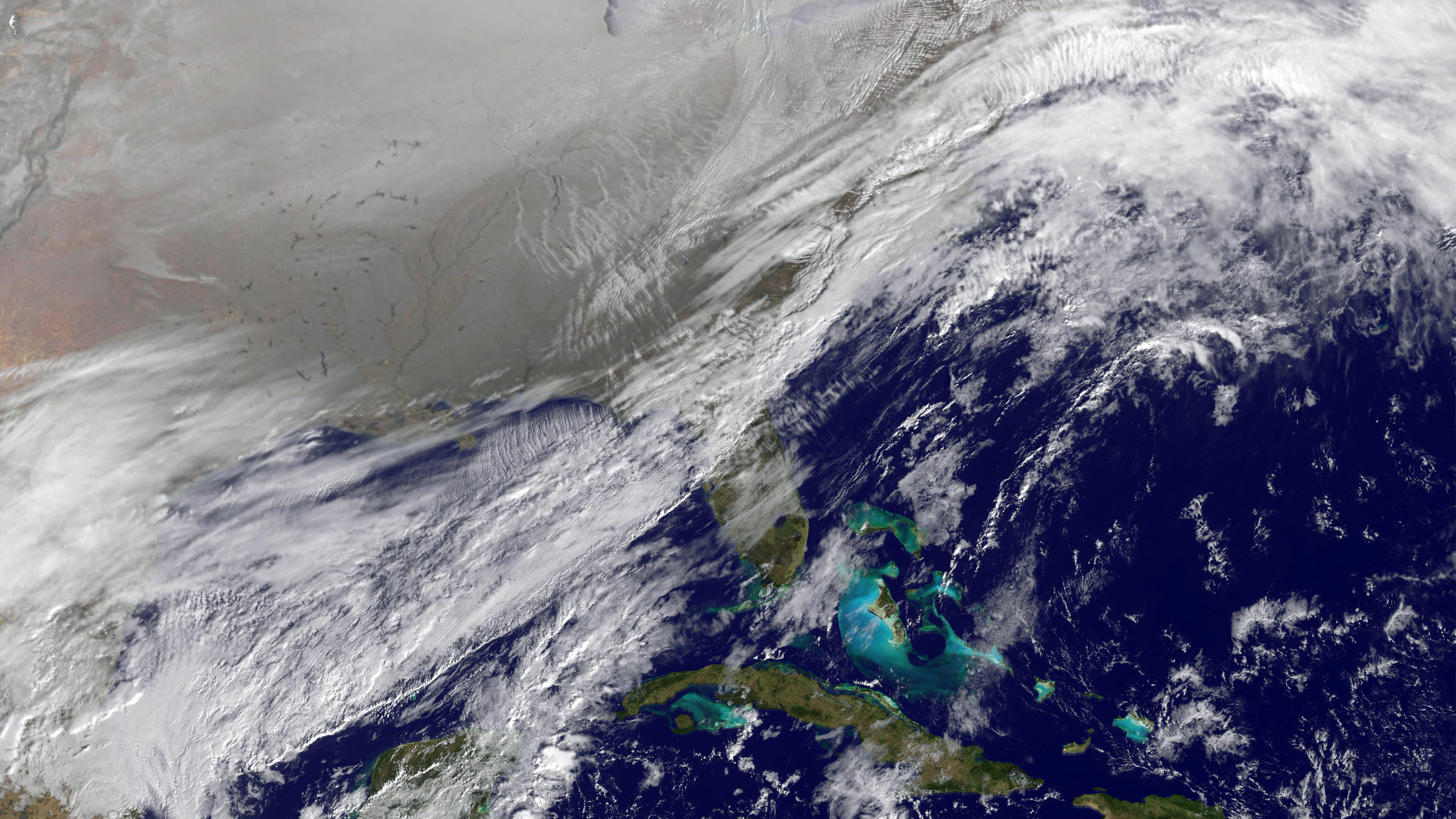

Though global temperatures are warming, winters in the Northern Hemisphere are still marked by cold snaps and extreme snowfall events — sometimes to an unprecedented extent, such as the 2021 deep freeze in Texas and Oklahoma that caused over $1 billion in damage.

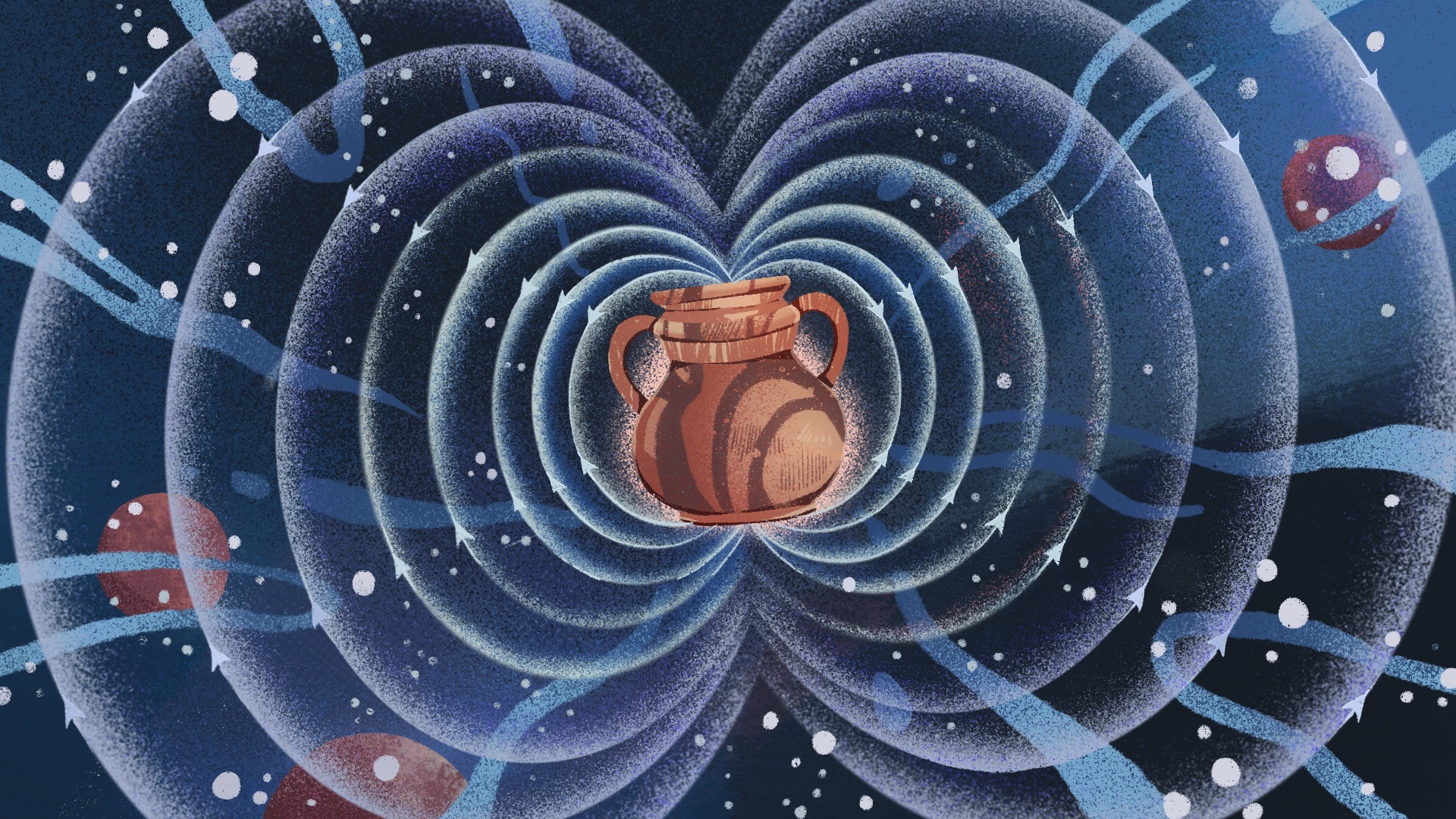

Now, a new study suggests that these cold extremes are due to an increasingly common pattern in the polar vortex, the zone of low pressure that usually circulates over the Arctic. Disruptions to this vortex cause it to deform and stretch, spewing cold air into Canada and the U.S. These disruptions are becoming more common as the Arctic warms.

“Overwhelmingly, extreme cold and severe winter weather, heavy snowstorms and deep snow, are associated with these stretched events,” study co-author Judah Cohen, the director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research and a visiting scientist at MIT, told Live Science.

Cohen and his team looked at how these events evolve in the stratosphere, the middle layer of the atmosphere that starts about 12 miles (19 kilometers) up. Understanding how these patterns shift could help meteorologists make longer-range forecasts, said Andrea Lopez Lang, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin—Madison who was not involved in the research.

“Knowing this information is useful for a lot of applications in energy [and] applications in insurance or reinsurance,” Lang told Live Science. “How cold is it going to get? Are pipes going to burst? Are insurance claims going to spike this winter?”

Usually, the polar vortex circulates around the North Pole like a spinning top. Occasionally, it collapses dramatically, which usually leads to polar air rushing toward northern Europe and Asia. These collapses can sometimes cause cold snaps in North America — but not always.

“There’s been this big question mark over what happens in North America,” Lang said.

Related: US suffers record-breaking cold: What’s going on with the polar vortex?

Cohen and his colleagues looked at stratosphere data from satellite observations between 1980 and 2021, as well as winter weather records from the same period. They found that, short of total collapse, the polar vortex often wobbles and stretches, like a figure skater flinging out an arm for balance in a tricky spin. There were five different common patterns in the stratosphere, the researchers reported in the journal Science Advances on July 11, and two in particular were linked to cold weather dipping into Canada and the U.S. during these stretch events.

Stretch events are increasing in general, Cohen said, but there has also been a shift in the type of stretches.

One of the stratospheric patterns tends to bring cold air toward the East Coast, while the other creates a chill in the Midwest and Plains region. Since 2015, the researchers found, the westerly pattern has been more common. It’s not entirely clear why, but this shift seems to be associated with La Niña, a pattern of unusually cold temperatures to the equatorial Pacific Ocean. In the last couple of decades, there have been multiple multiyear La Niña events.

The researchers were able to detect some regularities in the way the polar vortex shifts between the five patterns, which might help improve forecasts over the two- to six-week period, Cohen said. “In that shorter range is the poorest accuracy,” he said. “This paper can be helpful in that timeframe.”

One big question is how these polar vortex trends might change over time as the globe warms, Lang said.

Cohen and his team have been looking at that question as well. The polar vortex is controlled by waves in the atmosphere, he said, and right now the most influential standing waves is over Eurasia, with a warm ridge to the west and a cooler trough to the east, which in turn is driven by patterns of warming in the Arctic.

Currently, melting sea ice is increasing the temperature differences between west and east, strengthening the wave that can disrupt the vortex, Cohen said. If the sea ice disappeared, the pattern might collapse and flip. Instead of surprisingly cold winter events despite overall global warming, winter might suddenly become much toastier.

“We could become more like the Southern Hemisphere where you rarely get a breakdown of the polar vortex,” Cohen said, “and it would probably mean warmer midlatitudes and a colder Arctic.”