Bones from 4,000-year-old human skeletons discovered in Chile contain evidence of a rare form of Hansen’s disease, also known as leprosy, ancient DNA reveals.

Whereas the more common form of leprosy known today is caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium leprae, these skeletons had evidence of a different, rarer form of the disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium lepromatosis. The findings, published June 30 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, suggest that the two leprosy-causing bacteria evolved separately, on opposite sides of the globe, for thousands of years.

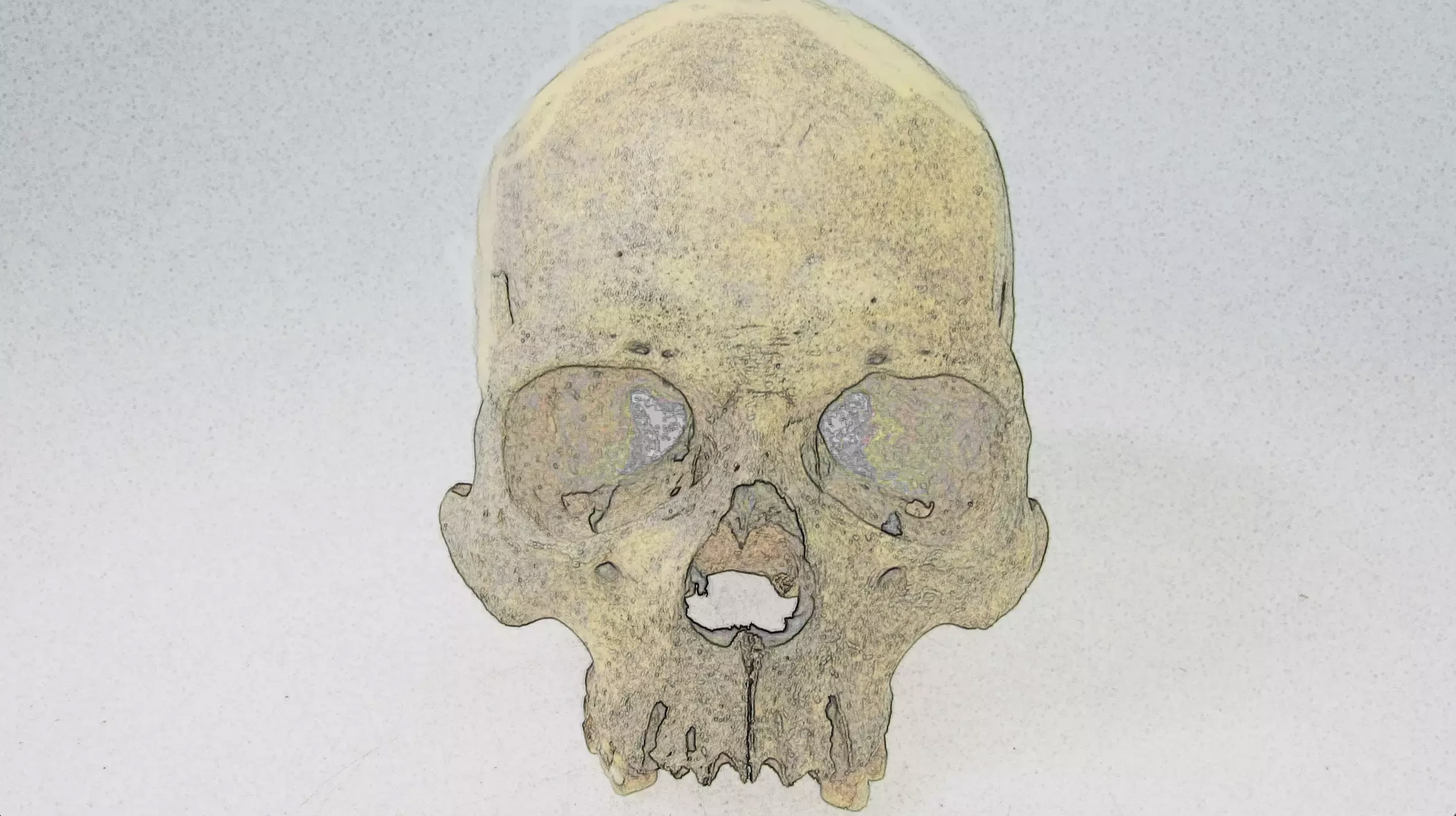

To make the discovery, the researchers reconstructed the genome of the M. lepromatosis from the remains of two adult males found at the neighboring archaeological sites of Cerrito and La Herradura in northern Chile.

“This reshapes our understanding of the disease’s history and raises new questions about how it arrived and spread in the Americas,” said Charlotte Avanzi, who studies the spread and genomics of leprosy at Colorado State University and was not involved with this study.

The origins of leprosy

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease with a host of painful symptoms, including skin lesions and limb numbness. It can lead to specific, observable changes in bone, and these characteristic transformations have been found in skeletons in Europe, Asia and Oceania from as far back as 5,000 years ago, according to a statement from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

The disease is usually caused by M. leprae, which has been widely studied. Archaeological analysis of bones from Europe point to Eurasia as the origin of the bacteria, likely emerging about 6,000 years ago during the Neolithic transition from foraging to farming.

Related: Disease-riddled skeletons suggest leprosy and smallpox ravaged medieval German village

Until now, there was no documented evidence of these changes in bone from the Americas before the colonial period, which suggested that leprosy was introduced to the region during that time. This research is complicated by the onslaught of pathogens that came to the Americas during that era and the difficulty of determining a diagnosis from ancient DNA, according to the statement.

“Ancient DNA has become a great tool that allows us to dig deeper into diseases that have had a long history in the Americas,” Kirsten Bos, a molecular paleopathologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and co-author of the study, said in the statement.

“We were initially suspicious”

The M. lepromatosis genome from the Chilean bones had “amazing preservation, which is uncommon in ancient DNA, especially from specimens of that age,” Lesley Sitter, a computational biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and co-author of the study, said in the statement.

After isolating the DNA of the pathogen, “we were initially suspicious, since leprosy is regarded as a colonial-era disease,” study co-author Darío Ramirez, a doctoral candidate of biological anthropology at the National University of Córdoba in Argentina, said in the statement. With further scrutiny, the team confirmed that they were indeed looking at evidence of leprosy caused by a type of bacteria that’s considered rare in the modern era.

This finding is significant, but not conclusive enough to determine if the disease originated in the Americas, Bos said. “So far the evidence points in the direction of an American origin, but we’ll need more genomes from other time periods and contexts to be sure.”

This work also helps to answer another major question: how did leprosy spread across such vast regions of the Americas? One idea is that the pathogen arose during an early peopling event in the Americas. Or, perhaps the pathogen was already in the Americas in an animal reservoir, and then it was contracted by people, the researchers wrote in the new study.

Scientists still don’t fully understand how the leprosy-causing bacteria spread, but their presence in such far corners of the world suggests there are environmental or animal factors responsible for transmission, Avanzi explained. “Identifying the origin and possible non-human reservoirs of M. lepromatosis is crucial for improving prevention and control strategies, both for human health and wildlife conservation,” she said.

This study complements findings by Avanzi and her team, which analyzed more recent remains from Canada and Argentina and also discovered evidence that M. lepromatosis was dispersed across the Americas before European colonialism.